God's Fight with the Dragon, Part II

Yahweh Is Enthroned for Slaying the Dragon of Chaos

The Hebrew Combat Myth

As a kingdom in the ancient Near East, Israel had its own combat myths and associated cultic traditions. In the Hebrew version, Yahweh is the storm-god warrior who subdues the Sea and its associate dragon; there is even evidence that, like Baal, he too battled Death. To these myths, their contexts, and the various uses to which they were put diachronically I now turn.

For the history of Yahwism—from ancient Israelite cult to Second Temple Judaism and beyond—the importance of the combat myth and the depiction of Yahweh as divine warrior can hardly be overstated. Indeed, Theodore Hiebert well summarizes this enduring significance when he writes:

The understanding of God as a warrior is grounded in the origins of biblical religion. The image of the divine warrior dominates the oldest Israelite poetry, remains a frequent characterization of God throughout the biblical period, and gains a new prominence in the apocalyptic literature of both Jewish and Christian communities.[1]

Understanding the evolution of this conception from ancient myth to crucial apocalyptic framework is necessary for an appreciation of its ultimate role in the Gospels.

So far, we have identified and analyzed various ancient Near Eastern combat myths by means of their thematic, motivic, and structural similarity. However, considerations of narrative progression become appreciably more difficult as we move into the Hebrew material since, as Andrew Angel has rightly noted, combat myth motifs are mostly found outside the context of strict narrative in Hebrew texts:

A definition [of the Hebrew combat myth] by plot would be very difficult as the tradition uses images frequently but it never places these images within a connected narrative… For example, the use of the Chaoskampf image in Isa. 17.12-13 can hardly be deemed a story, and the narrative is partial even where elements of story are present, e.g. Ps. 18.4-15.[2]

Indeed, the hints that we get of the Hebrew combat myth from the Prophets and Psalms, for example, presume the story rather than tell it. For this reason we must largely set aside our narrative schema in this chapter, and instead rely primarily on the knowledge gleaned from the previous investigation of the combat myth genre, particularly its common themes and imagery. Later, we may return to the narrative schema when appropriate.

Yahweh vs. Sea (Yam)

Like Baal, Yahweh’s chief enemy in the Hebrew combat myth is Yam, the raging Sea. As a representative of Chaos, Sea must be defeated if order and fertility are to be secured in the cosmos. So we read, in scattered allusions from the Psalms and Prophets, how the Israelite storm-god battles the chaos-enemy. One text reads:

Was your wrath against River, O Yahweh?

Or your anger against River,

or your rage against Sea,

When you drove your horses,

your chariots to victory?

You brandished your naked bow,

sated were the arrows at your command.

…You trampled the Sea with your horses,

churning the mighty waters. (Hab 3:8-9a, 15)

Yahweh’s conflict with Sea/River is clearly analogous to Baal’s enemy Prince Sea/Judge River—both “Yam(m)” and “Nahar” in the Semitic languages, and both frequently noted in poetic parallelism.[3] Here the trampling of the chaos-enemy is attested, particularly reminiscent of how Marduk trampled the primordial Sea after sating his lightning-bolt arrows.

Again, the roaring thunder that accompanies such lightning was understood as the storm-god’s mighty voice, and so Yahweh’s chief battle weapon is often described simply as his voice, roar, or, most frequently, his rebuke (Hebrew gʿr):

He rode on a cherub, and flew; he came swiftly upon the wings of the wind.

He made darkness his covering around him,

his canopy thick clouds dark with water.

Out of the brightness before him

there broke through his clouds hailstones and coals of fire.

Yahweh also thundered in the heavens,

and the Most High uttered his voice.

And he sent out his arrows, and scattered them;

he flashed forth lightnings, and routed them.

Then the channels of the Waters were seen,

and the foundations of the world were laid bare

at your rebuke, O Yahweh,

at the blast of the breath of your nostrils. (Ps 18:10-15)

Here, in addition to the scattering of the raging Sea waters, we find all anthropomorphic characterizations of the storm-god’s weapons: his lightning as arrows and his thunder as his rebuking voice. At his rebuke the Sea recoils and reveals the foundations of his creation.

We find similar examples of Yahweh rebuking the chaos-waters in Psalm 106:9, Isaiah 17:13 and 50:2, and Nahum 1:4. All relate the basic idea that at his rebuke (i.e., his mighty voice, the thunderous crash of his lightning) the Sea, like a defeated enemy, hurries away and recedes to its rightful boundaries. Thus order is established and the chaotic waters are contained. Another psalm draws all of these aspects together:

…You have laid the beams of your chambers on the Waters,

You make the cloud your chariot,

you ride on the wings of the wind…

…You set the earth on its foundations,

so that it shall never be shaken.

You cover it with the Deep as with a garment;

the Waters stood upon the mountains.

At your rebuke they flee;

at the sound of your thunder they take to flight.

…You set a boundary that they may not pass,

so that they might not again cover the earth. (Ps 104:3, 5-7, 9)

Here Yahweh is none other than the storm-god in his cloud-chariot who tames the chaotic Sea by his imposition of order. Indeed, as in other combat myths, his defeat of Sea is intricately linked to cosmogony and creation. Ninurta created an irrigation system that stopped the waters from remaining upon the mountains; Marduk created heaven and earth out of Sea’s body. So Yahweh likewise keeps the waters from flooding the mountaintops and establishes an ordered, differentiated cosmos.

Though most prevalent in the Psalms (for reasons considered below), references to this cosmic battle are found elsewhere in the Hebrew Bible. In poetic terms, the author of Job makes use of Yahweh’s contention with Sea as he reflects on the unthinkable power of Yahweh and the futility of fighting against him—as Sea had tried, but failed:

If one wished to contend with him,

one could not answer him once in a thousand.

He is wise in heart, and mighty in strength

—who has resisted him, and succeeded?—

…[he] who alone stretched out the heavens

and trampled the waves of Sea. (Job 9:3-4, 8)

So we encounter the trampling of the Sea and its connection with Creation. Elsewhere, feeling that God is now contending against him, Job laments:

Am I Sea, or Dragon,

that you set guard over me?

…Why have you made me your target?

Why have I become a burden to you? (Job 7:12, 20)

This Dragon to which Job refers is another enemy that Yahweh slays in his battles against the Sea and the forces of Chaos.

Yahweh vs. the Dragon

Like Baal and the other storm-gods, Yahweh does battle with the draconic helpers of chief chaos-enemy. Thus the seven-headed sea dragon Litan from the Baal Cycle reappears, with its name only slightly changed, as the many-headed sea dragon Leviathan:

Yet God my King is from of old,

working salvation in the earth.

You divided Sea by your might;

you shattered the heads of Dragons in the Waters.

You crushed the heads of Leviathan;

you gave him as food for people in the wilderness.

You cut openings for springs and torrents;

you dried up ever-flowing streams.

Yours is the day, yours also the night;

you established the luminaries and the sun.

You have fixed all the bounds of the earth;

you made summer and winter. (Ps 74:12-17)

Here, the thematic concerns with both kingship and agricultural regularity are present, while, with regard to motifs, we encounter the dismembering/dividing of the enemy Sea. Indeed, the relationship of combat and cosmogony is particularly pronounced in the Hebrew tradition. After Yahweh crushed the heads of the dragons in primordial time (cf. Marduk and Baal crushing the heads of their draconic Sea nemeses), he established the celestial objects, the boundaries of the Earth, and the seasons. In perhaps the most fascinating similarity, however, Yahweh casts Leviathan’s corpse in the desert to serve as food—just as Anat scattered the Dragon/Yamm in the desert, as well as the body of Mot (which was then eaten by birds). Thus we find the topos present in the Hebrew tradition as well, in which the defeated chaos-monster is divided, its body serving as nourishment in a once-barren place.

An extensive description of Leviathan occupies Job 41. Here, Yahweh boasts to Job about his conquest of the sea monster:

Can you draw out Leviathan with a fishhook?

Or press down his tongue with a cord?

Can you put a rope in his nose

or pierce his jaw with a hook?

…Will you play with him as with a bird,

or will you bind him for your maidens?

…Lay your hand on him; Remember the battle;

you will not do it again! (vv. 1-2, 5, 8, NASB).

Again we find the binding motif, as Yahweh himself boasts of ensnaring Leviathan—even specifically muzzling the Dragon just as Anat muzzled Tunnan. Elsewhere, Yahweh makes a similar boast:

The Lord said: “I stifled the Serpent, muzzled the Deep Sea. (Ps 68:23)[4]

Thus, similar to the Canaanite combat myths, Yahweh is said to have muzzled the Dragon/Sea in the course of their battle.

Other passages speak of the slaying of Rahab, whose name means “The Boisterous One” and thus, as John Day observes, “an apt term for the personified raging sea.”[5] Rahab is certainly a chaos-monster, and may in fact be simply another name for Leviathan.[6] Psalm 89 links the taming of the Sea, the crushing of Rahab, and Creation:

You rule the raging of the Sea;

when its waves rise, you still them.

You crushed Rahab like a carcass;

you scattered your enemies with your mighty arm.

The heavens are yours, the earth is also yours;

the world and all that is in it—you have founded them. (Ps 89:9-11)

Similarly, Job meditates on the unrelenting anger of Yahweh in considering his own plight:

God will not turn back his anger;

the helpers of Rahab bowed beneath him.

…How then can I answer him,

choosing my words with him? (Job 9:13-14)

The thought again echoes the trampling motif: the helpers of the sea-dragon Rahab lie in submission beneath Yahweh’s feet as defeated enemies of the angry divine warrior. So Ninurta trampled Azag’s helpers, Baal Yamm’s helper(s), and Marduk Tiamet’s.

Yahweh vs. Death (Mot/Sheol)

It is debatable whether explicit mention is made in the Hebrew Bible of any battle between Yahweh and Death (Hebrew “Mot”). However, given Israel’s traditional continuity with the Canaanite combat myths of Baal vs. Sea/River and the Dragon, the existence of such a myth is quite plausible. Indeed, investigating such a hypothesis yields intriguing and suggestive evidence that such a myth did exist, and even persisted for centuries in tradition despite its scarcity within canonized texts.

Even in canonical Hebrew texts, however, the personification of Death as a pernicious supernatural agent often transcends mere poetic expression. Indeed, the ancient Israelites clearly shared many mythic conceptions of Death and the underworld with the Canaanite tradition.[7] So, for example, Psalm 49:14 speaks of foolish men in these terms:

Like sheep they are appointed for Sheol;

Death shall be their shepherd;

straight to the grave they descend,

and their form shall waste away;

Sheol shall be their home.

This idea of Death as shepherd may relate to a tradition attested in the Ugaritic texts. In KTU 1.6.ii.21-23, Death boasts of taking Baal as a kid in his mouth and carrying him away like a lamb.[8]

As the passage illustrates, Death is often paired with Sheol, the underworld, and indeed the two often appear to be essentially synonymous. Sheol is thus a kind of periphrasis for Death/Mot himself, as the poetic parallelism of Habakkuk 2:5 suggests:[9]

…The arrogant do not endure.

They open their throats wide as Sheol;

like Death they never have enough.

They gather all nations for themselves,

and collect all peoples as their own.

This verse exemplifies the most notable Israelite continuity with the Canaanite conception of Death: his rapacious appetite. We saw that, in the Ugaritic texts, Death is characterized by his insatiable appetite, and even swallows Baal himself. The same is true of Death in ancient Israelite conceptions. Thus Proverbs 27:20 declares, “Sheol and Abaddon [Destruction] are never satisfied,” and Proverbs 30:15c-16 reads:

Three things are never satisfied;

four never say, “Enough”:

Sheol, the barren womb,

the earth ever thirsty for water,

and the fire that never says, “Enough.”

Sheol is even depicted as the swallower, whose consumption leads the dead into “the Pit”:

Like Sheol let us swallow them alive

and whole, like those who go down to the Pit. (Prov 1:12)

Likewise Isaiah 5:14:

Therefore Sheol has enlarged its appetite

and opened its mouth beyond measure;

the nobility of Jerusalem and her multitude go down,

her throng and all who exult in her.[10]

Seeing that Death was often understood as a supernatural agent with the same characteristics as the Canaanite god, some scholars have posited the existence of a combat myth between Yahweh and Death similar to the combat between Baal and Death. Indeed, W. F. Albright sees the myth reflected in Habakkuk 3:8-14, translating the text:

Is Thy wrath, O Yahweh, against River

—Against River is Thy Wrath <directed ?>

Or is Thine anger against Sea ;

That Thou dost ride Thy horses,

Bare dost Thou strip Thy bow,

The mountains saw Thee and quaked,

The clouds streamed with water,

The exalted one, Sun, raised his arms,

By the light of Thine arrows they move,

In anger dost Thou tread the earth,

Going forth to save Thy people,

Thou didst smite the head of wicked Death,

Thou didst pierce <his>head in the fight,

Thy chariot <which bringeth>victory ?

Sated by the fight which Thou hast decreed.

The Deep gave forth its voice ;

The rivers, which cleave the earth.

Moon stood<on>his lordly dais ;

By the lightning sheen of Thy spear !

In wrath dost thou thresh the nations,

To save<the people>of Thine Anointed.

Destroying (him) tail-end to neck ;

While his followers (?) stormed…?[11]

Clearly, this passage is rife with Chaoskampf imagery, beginning with allusions to Yahweh’s battles against Sea and River, then turning to the battle with Death: the same progression, it should be noted, as the Ugaritic material. Albright states that here “we have a vivid sketch of the prostrate body of a dragon,”[12] suggesting that Death too was understood as a chaos-monster.

This translation is given additional weight by two aspects not noted by Albright. First, verse 14 in the Masoretic text refers to the enemy’s desire to devour (Heb. ʾkl). So the NRSV describes the enemies “gloating as if ready to devour the poor…” The idea is retained in the Septuagint with the participle esthiōn. Albright however does not translate the line, thinking it corrupt. Though this is possible, should the presence of the enemy’s desire to devour reflect any aspect of the original, it would be entirely fitting with the nature of Death, the swallower, who is characterized by his insatiable appetite. Secondly, when we appreciate that Death/Sheol and the underworld are often referred to as “the Earth,”[13] it is possible to read the treading of Earth as a part of Yahweh’s battle with Death. The trampling of Earth would thus be similar to the punishment of Sea,[14] as would the smiting/piercing of his head (cf. Baal crushing Yamm’s head).

Recognizing Earth as another name or epithet for the underworld deity, Mary Wakeman has proposed the existence of a chaos-monster whose associations were primarily terrestrial, rather than oceanic (as they are with Leviathan/Rahab). While Behemoth has long been understood as the terrestrial land monster, her association of this chaos-monster with Mot is novel.[15] If correct, Mot was understood as a terrestrial chaos-monster which Yahweh defeated as he defeated Yam, the chaos-monster of the sea. Such an interpretation would fit very well here with the description of Death’s draconic presentation and the mention of his tail.

Later evidence for a battle between Yahweh and Death is found in the book of Isaiah. The prophet addresses Yahweh:

For you have been a stronghold to the poor,

a stronghold to the needy in his distress,

a shelter from the storm and a shade from the heat;

for the breath of the ruthless is like a storm against a wall,

like heat in a dry place.

You subdue the noise of the foreigners;

as heat by the shade of a cloud,

so the song of the ruthless is put down.

On this Mountain, Yahweh of Hosts will make for all peoples

a feast of rich food, a feast of well-aged wine,

of rich food full of marrow, of aged wine well refined.

And he will swallow up on this Mountain

the covering that is cast over all peoples,

the veil that is spread over all nations.

He will swallow up Death forever. (Is 25:4-8, ESV).

Here the prophet seems to draw on the Levantine agricultural underpinnings of the combat myth—between the fecund autumn of the storm-god and the barren, hot summer of Mot. We recall that, as Mark Smith puts it, “both the Baal-Yamm and Baal-Mot conflicts lead up to the autumn rains”[16] and that

each major part of the [Baal] cycle uses the imagery of the fall interchange period… This period witnesses the alternation of the eastern dry winds of the scirocco with the western rain-bringing winds coming off the Mediterranean Sea until the western winds finally overtake the eastern winds.[17]

Here this seasonal interchange becomes a metaphor for Yahweh’s salvation of his people: the storm-god’s rainclouds overcome the oppressive heat of summer, i.e., Death. This metaphor is continued with the image of the feast. The abundant feast of Yahweh on the citadel of Jerusalem recalls a first-fruits or harvest festival. We have seen that just such a festival likely provided the cultic context for the Ugaritic combat myths—including Baal’s battle with Death—and, as we shall see, the Israelite combat myths as well. Finally, behind the last verse undoubtedly lies not only the mythological motif of Death as the swallower, but indeed the whole combat myth in which Death swallows the storm-god Baal.[18] Here, the prophet has reversed the idea: it is the storm-god Yahweh who will swallow Death! That the author could draw upon such a tradition suggests that the mythic battle likely had a place in the Hebrew tradition too, wherein Yahweh defeats Death.

Additional evidence for the existence of a combat myth between Yahweh and Death will be considered later in light of apocalyptic texts which may, like the above passage from the so-called “Isaianic Apocalypse,” allude to such a myth. Briefly, however, we shall note that in Revelation 20, after defeating the Dragon, Christ defeats Death and Hades by throwing them into a lake of fire—a likely reflex of the ancient combat myth progression. Likewise, some of Paul’s letters seem to evince a knowledge of such a myth.[19] Again, these aspects shall be considered in greater detail in later chapters. For now, we may simply conclude that, though evidence is limited for a combat myth between Yahweh and Death in our oldest extant sources, it is quite plausible that such a myth existed. In it, Yahweh, not Baal, battled Death as the rain-bringing storm-god, and proved victorious.[20]

Yahweh vs. Israel’s Enemies

As noted in Chapter 1, the thematic significance of divine kingship in ancient Near Eastern combat myths obliged associations with earthly kingship, since the former both reflected and idealized the latter. For this reason, historical and political realities often inform combat myths or, rather, there is a kind of dialectic of myth and history: history informed myth, while myth was employed to interpret and articulate history. Until now, we have not considered instances in which specific historical contexts are reflected this way, though Clifford assures that this historical element is indeed present in most ancient Near Eastern Chaoskampf myths. For example, Ninurta’s enemies, Azag and Anzu, reside in the northeastern mountains, which were in fact the homeland of the Gutians and other enemies of the Mesopotamian plain dwellers.[21] Thus, historical conflicts are sublimated to the realm of myth; the Gutians are equated with chaos-monsters, the Babylonian king with Ninurta. Similar historical/political interpretations have been applied to the Baal Cycle, though such readings are often more conjectural.[22]

Again, these associations were dialectical. Myth and history informed one another; dependence went both ways. Thus historical powers drew as much from myth as myth from historical powers. In the process, both were reaffirmed. In Canaan and Egypt, for example, the powers of the mythic storm-god were applied to the ruling kings. Strikingly, the associations draw specifically from generic motifs of the combat myth. Thus, in one text, the Egyptian pharaoh is said to “give forth his cry in the sky like Baal,” a clear reflection of the god’s mighty voice motif.[23] Likewise, the victory stele of Tutmosis III “renders this king in terms reminiscent of Baal-Haddu,” according to Mark Smith and Wayne Pitard.[24] It reads in part:

I have come that I may cause You to trample on the eastern land and tread down those who are in the regions of Tonuter; that I may cause them to see Your Majesty as a lightning flash, strewing its levin-frame and giving its flood of water…I have come that I may cause you to trample on the Islanders in the midst of the sea, who are possessed with your war shout…[25]

The meteorological imagery is obvious, but most remarkable here is the presence of motifs drawn directly from the combat myth: the trampling motif (which equates “the Islanders” with the chaos-monster “in the midst of the sea”), and the allusion to the storm-god’s war-cry—his mighty voice which causes the enemy to quake and surrender. The earthly king thus mirrors not just Baal, but triumphant Baal from the combat myth. Myth provides a crucial framework through which history is interpreted.

This historicizing tendency is particularly pronounced in the Hebrew tradition.[26] In one respect, its presence in royal propaganda and ideology is comparable to other kingdoms of the ancient Near East. So Smith compares the above texts to Psalm 89:26, where Yahweh invests the Davidic king with the powers of the divine warrior:

And I shall set on Yamm his hand, and on River(s) his right hand.[27]

So the Israelite king was presented as a reflection of the victorious storm-god. However, in another respect, the pronounced inclination to historicize the combat myth stems from a rather unique theological conception. Ancient Israelites emphasized their god as acting within history—not only in the sacred, primordial past—in a way that invited poets to construe historical events in terms of the combat myth.[28]

Indeed, this was the use to which the myth was put in the earliest Hebrew traditions, when poets articulated Yahweh’s defeat of the Egyptian pharaoh’s forces in the language of the combat myth.[29] So Exodus 15:[30]

Yahweh is a warrior;

Yahweh is his name.

Pharaoh’s chariots and his army he cast into the Sea;

his picked officers were sunk in the Red Sea.

The Deep covered them;

they went down into the depths like a stone.

Your right hand, O Yahweh, glorious in power—

your right hand, O Yahweh, shattered the enemy.

In the greatness of your majesty you overthrew your adversaries;

you sent out your fury, it consumed them like stubble.

At the blast of your nostrils the Waters piled up,

the Floods stood up in a heap;

the Deep congealed in the heart of the Sea.

…You brought [the people] in and planted them on the Mountain of your

possession,

the Place, O Yahweh, that you made your abode,

the Sanctuary, O Yahweh, that your hands have established.

Yahweh will reign forever and ever. (vv. 3-8, 17-18)

Here, Yahweh’s defeat of the Sea is artfully combined with and reflective of his defeat of Egypt. Indeed, the defeat of Sea is the means of Egypt’s ruin, for it is the dividing of Sea at the “blast from his nostrils” that allows Israel to cross and Egypt to be consumed. Thus, the common images of the combat myth infuse the “historical” account of a political victory. Moreover, Yahweh’s victory in this combat at sea concludes with his declaration as king: the expected progression of the combat myth. He even guides Israel up his mountain to his “Place” and “Sanctuary,” leading his people in procession to his house (i.e., Temple).

Finally, as we have seen, ancient Near Eastern combat myths were sometimes cosmogonies, and this was certainly true in the case of the Hebrew myth. Now, because the Exodus tradition was Israel’s primary foundation story—the creation account, as it were, of the ancient Israelites’ world—it is not surprising that we find the Exodus articulated in terms of the combat myth.[31] Indeed, this is an essential aspect of the Exodus story. The Exodus is, in fact, but a variation of the combat myth—an historicized version of the combat myth genre. Appreciating this point will be critical in our eventual assessment of Exodus typology in the Gospel of Mark.

Moving beyond the earliest poetic material, we see the combat myth employed throughout the Hebrew tradition in order to help frame specific political/historical situations. Indeed, various prophets liberally apply its imagery in attempts to heighten their political denouncements of rulers or enemies of Israel. So, for example, Isaiah 14:12-19 paints the king of Babylon as the cosmic adversary of the combat myth:

How you are fallen from heaven, O Day Star, son of Dawn!

How you are cut down to the ground, you who laid the nations low!

You said in your heart, “I will ascend to heaven;

I will raise my throne above the stars of God;

I will sit on the Mount of Assembly on the heights of Zaphon;

I will ascend to the tops of the clouds,

I will make myself like the Most High.”

But you are brought down to Sheol, to the depths of the Pit.

Those who see you will stare at you, and ponder over you:

“Is this the man who made the earth tremble, who shook kingdoms,

who made the world like a desert and overthrew its cities,

who would not let his prisoners go home?”

All the kings of the nations lie in glory, each in his own tomb;

but you are cast out, away from your grave, like loathsome carrion,

clothed with the dead, those pierced by the sword,

who go down to the stones of the Pit,

like a corpse trampled underfoot.

The shamed king is described with language steeped in mythological imagery, particularly Chaoskampf imagery. He is presented as an attempted usurper, a challenger to Yahweh’s throne in the same way that Yamm and Mot challenged Baal’s kingship; or Anzu, Enlil’s; or Azag, Ninurta’s. He would enthrone himself above Yahweh, on the traditional mountain of the Canaanite storm-god (Zaphon). But instead, the king is defeated, hurled into the “the depths of the Pit” for his offense and cast out from his grave to be eaten (perhaps reflecting the scattering motif). Certainly the combat myth trampling motif is employed here. Such is the fate of rebels who stand against the true cosmic king, Yahweh.

The prophet Ezekiel employs very similar imagery in his prophecies of the imminent destruction which Yahweh will bring upon Israel’s hubristic political enemies. So Yahweh summons Ezekiel to deliver his ominous message regarding the presumptuous kings:

Mortal, say to the Prince of Tyre, Thus says the Lord God:

Because your heart is proud and you have said, “I am a god;

I sit in the seat of the gods, in the heart of the seas,”

yet you are but mortal, and no god,

though you compare your mind with the mind of God.

…Therefore thus says the Lord God:

Because you compare your mind with the mind of a god,

therefore, I will bring strangers against you, the most terrible of the

nations;

they shall draw their swords against the beauty of your wisdom

and defile your splendor.

They shall thrust you into the Pit,

and you shall die a violent death in the heart of the seas. (Ezek 28:2, 6-8)

Again, the cosmic language of the combat myth is employed in this political execration. As above, the ruler boasts of his enthronement as a god. While the references to the seas are ostensibly due to Tyre’s geographical position as a city jutting out into the Mediterranean, they may also reflect a subtle equation of the Prince with the oceanic chaos-enemy, the monster “in the midst of the sea.” Like the combat myth adversaries, however, the would-be king is defeated by Yahweh, and hurled into the Pit.

Equation of the king with the chaos-monster is more explicit in the prophecies directed at the Egyptian pharaoh, the first of which comes a few verses later, presented in parallel form to the last denunciation:

Mortal, set your face against Pharaoh king of Egypt, and prophesy against him and against all Egypt; speak, and say, Thus says the Lord God:

I am against you,

Pharaoh king of Egypt,

the great Dragon sprawling

in the midst of its channels,

saying, “My Nile is my own;

I made it for myself.”

I will put hooks in your jaws,

and make the fish of your channels stick to your scales.

I will draw you up from your channels,

with all the fish of your channels

sticking to your scales,

I will fling you into the desert,

you and all the fish of your channels;

you shall fall in the open field,

and not be gathered and buried.

To the animals of the earth and to the birds of the air

I have given you as food. (Ezek 29:2-5)

The Pharaoh, like the King of Tyre, is guilty of unchecked hubris that challenges the supremacy of Yahweh. In his pride he rebels against the true supreme deity, viewing himself as equal to the true Lord of Creation. To this Yahweh responds with the imagery of the combat myth. The Pharaoh is nothing more than the Dragon that Yahweh triumphantly vanquished. He is no greater than Leviathan, the dragon in the sea which Yahweh has slain and cast into the desert as food. Thus is the traditional topos reemployed, in which the chaos-enemy is made food in the desert. Here, the topos provides a metaphor for the punishment of the Egyptian pharaoh.

Indeed, the association of the arrogant rebel king with the chaos-monster Leviathan seems clear. Compare the above passage with those texts which elsewhere describe the Dragon:

I will put hooks in your jaws, and make the fish of your channels stick to your scales.

I will draw you up from your channels…

(Ezek 29:4)

The great dragon sprawling in the midst of its channels…

…I will fling you into the desert…You shall fall in the open field, and not be gathered and buried. To the animals of the earth and to the birds of the air I have given you as food.

(Ezek 29:3, 5)

Can you put a rope in its nose, or pierce its jaw with a hook?”

“Can you draw out Leviathan with a fishhook, or press down its tongue with a cord?

(Job 41:2,1)

…you broke the heads of the dragons in the waters.

You crushed the heads of Leviathan; you gave him as food for the people in the wilderness.

(Ps 74:13-14)

The specific imagery of the combat myth is even more explicit in the denouncement of the Pharaoh in chapter 32:

You consider yourself a lion among the nations,

but you are like a Dragon in the Seas;

you thrash about in your streams,

trouble the water with your feet,

and foul your streams.

Thus says Yahweh God:

In an assembly of many peoples

I will throw my net over you;

and I will haul you up in my dragnet.

I will throw you on the ground,

on the open field I will fling you,

and will cause all the birds of the air to settle on you,

and I will let the wild animals of the whole earth gorge themselves wit

you.

I will strew your flesh on the mountains,

and fill the valleys with your carcass.

I will drench the land with your flowing blood

up to the mountains,

and the watercourses will be filled with you.

When I blot you out, I will cover the heavens,

and make their stars dark;

I will cover the sun with a cloud,

and the moon shall not give its light. (vv. 1-7)

The Pharaoh is the raging chaos-monster, the Dragon in the Sea, whom Yahweh binds in his net, then divides and scatters—specifically over the mountains here, in remarkable similarity to the way Ninurta scatters and strews Azag over the mountains. All of this is done in the context of the storm theophany, as Yahweh covers the sky with his clouds, casting the scene of this Chaoskampf (as in others) into darkness.

So is history interpreted in light of the combat myth. Israel’s political enemies are the chaos-monsters; Yahweh—acting through Israel generally, or her king specifically—is the mighty storm-god who shall vanquish them. Such historicization of the combat myth was employed in the earliest Hebrew poetry, particularly in characterizations of the Exodus. However, it continues throughout the biblical period, especially in the Prophets. Eventually, interpretations of political conflict through the framework of the combat myth become a vital feature of Jewish apocalypticism, as we shall see in Chapter 3.

The Combat Myth in Hebrew Cult

Until the turn of the twentieth century and the achievements of comparative scholarly studies, Yahweh’s battle with Leviathan and the raging Sea remained largely opaque—a theme seemingly scattered haphazardly throughout the Psalms or the occasional prophetic passage in enigmatic references. Even today, the idea of Yahweh battling a giant sea dragon remains quite foreign to many. To suggest then that it once provided perhaps the most crucial mythic narrative for ancient Israelite religious practice may sound presumptuous to say the least. Nevertheless, there is ample reason to believe that it once lay at the heart of ancient Israelite religion.

The insights of Paul Hanson are a helpful starting place for mitigating this discrepancy between the myth’s apparent infrequency in biblical texts and its ancient cultic significance. According to Hanson, the Bible we have to today is not representative of the ancient cult of Yahweh as practiced at the Jerusalem Temple, but rather reflects the minority views of certain prophetic circles which ultimately came to dominance after the Exile. In Hanson’s analysis, most of the prophets make relatively scant use of the Hebrew combat myth because their theological programs often stood in marked contrast to the royal theology of the Jerusalem court and cult, where the combat myth played a primary role. However, at the court and Temple cult, argues Hanson,

the visionary element of myth was safeguarded against the rival theology of prophecy, and although later developments led to a canon dominated by prophetic Yahwism, the royal psalms preserve examples of the type of theology which was in a real sense the national orthodoxy.[32]

Thus, as liturgical texts from the cult, the Psalms provide us with insight into the nature of Israelite religion as practiced “officially” at the Jerusalem Temple, and not the idiosyncratic views of the rival prophetic circles who generally diluted the mythological element. In the temple liturgy, writes Hanson, “the ritual pattern of the conflict myth not only survived, but flourished.”[33]

Though imperfect, Hanson’s analysis is helpful in at least two respects. First, it draws attention to the fact that the Prophets are not necessarily the best representatives of ancient Israelite religion. Consequently, if the combat myth does not appear to play a dominant role in prophetic literature—which, indeed, now dominates the biblical canon—this does not mean that it did not play such a role in the more prevalent conceptions and rites of the cult. Secondly, the combat myth did play a central role in the “official” Israelite cult. This is demonstrated by an analysis of the Psalms, which I present below. Since the cult was the primary means by which most ancient Israelites would have engaged with and enacted shared religious conceptions, one is justified in saying that the combat myth was a central aspect of religious life in ancient Israel.

While this analysis of Hanson’s might be enough to justify hypothesizing a particular prominence of the combat myth in popular religious practice, a necessary critique actually strengthens the argument. For Hanson argues that, contrary to the Chaoskampf-dominated cult, Yahwistic prophecy downplayed the mythological element and thus made scant use of the combat myth. Yet, as we have seen (and shall have ample opportunity to cite in further detail), the combat myth also flourished in prophetic circles. To be sure, its application in prophetic literature is less explicit (leading to a canon seemingly limited in Chaoskampf material). But this is not because the theological agenda of classical prophecy necessarily sought to downplay mythological material. Rather, the myth appears more diluted because the role it plays in prophetic literature is essentially different: as allusion and poetic reference, not strict presentation.

The combat between Yahweh and the chaos-monsters appears nowhere in the Hebrew bible as a pure narrative. We have, as it were, no Yahweh Cycle as we have a Baal Cycle. While the Psalms indeed come closest to this (probably because they also reflect a liturgical origin), even they are essentially allusive. Indeed, whether a strict narrative of Yahweh’s battles with Chaos ever existed as such, we cannot now know (barring, of course, some new archeological evidence). Thus, we acquire our sense of the story through metaphor, suggestion, and allusive images coupled with recurrent themes. This is particularly true in the prophetic literature, where the allusive and metaphorical use of Chaoskampf imagery constitutes its primary mode of presentation.

However, having reconstructed the general story (primarily through the more explicit imagery of the Psalms as well as in comparison with other ancient Near Eastern combat myths), a host of hitherto unrecognized allusions to the Hebrew combat myth in the Prophets come to light. Many of these allusions are considered below, and are employed, sometimes extensively, by Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, Amos, Habakkuk, Zechariah, and Malachi. In this sense then, the combat myth has in fact always played a considerable role in most biblical texts, we had simply lacked the central conception upon which these more subtle allusions were predicated. With careful analysis, however, we see that the combat myth is common to and pervasive in both the Psalms and the Prophets.

Indeed, appreciating the dominance of the combat myth in the cult puts the prophetic material in context: the Prophets assume this dominance in order to allude to it. Prophetic applications of the combat myth could be so subtle and allusive precisely because the myth was a given. In this sense, the seemingly diluted role of the myth in prophecy—far from being rooted in a fundamental tension between prophecy and “orthodoxy”—provides additional testimony to the myth’s general popularity. Just as a jazz musician relies on his listener’s knowledge of a popular tune in order to riff on it and add harmonic color, the prophets could presume familiarity with the myth in order to adapt and augment it.

All of this helps to highlight the fundamental role the combat myth played in the religious life of ancient Israel. The story of Yahweh’s battles with the forces of Chaos clearly undergirds both the national cult, represented in the canon essentially by the Psalms, but also the Prophets, albeit less perceptibly.

With this important qualification, I return to Hanson’s analysis of the official Jerusalem cult through its extant liturgical literature, the Psalms. Here, we recall, Hanson says that the combat myth “flourished,” appearing frequently in a traditional form he calls the “Divine Warrior Hymn.” Remarkably, this form follows essentially the same progression as the combat myth schema we have been using. Thus, we often see:

1) Threat

2) Combat – victory over enemy

3) Salvation of his people

4) Manifestation of universal reign

5) Victory shout

6) Procession

7) Shalom (return to fertility – new creation)

In Hanson’s terminology, the “shalom” represents the bounty and abundance consequent to Yahweh’s victory over Chaos. This is the agricultural rejuvenation which occurs because of the storm-god’s victory. The “victory shout” is the mighty voice/battle cry of the divine warrior while the “manifestation of universal reign” is analogous to the storm-god’s accession to kingship.

These essential elements of the Divine Warrior Hymn, he says, “can be recognized in numerous psalms from various periods in the biblical psalter.”[34] I present his extensive list below:

Psalm 2

1-3 Threat: Conspiring of the nations

4-5 Combat – victory over enemy

8-11b Manifestation of universal reign

11c Victory shout

Psalm 24

1 Manifestation of universal reign

2 Combat vs. seas/rivers- victory

(3-6 Entrance Torah)

7-10 Victory shout

Procession after victory to temple

Psalm 46

2-7 Threat: Chaos and nations

Combat – victory over enemy

8 Salvation of his people

9-12 Manifestation of universal reign

Psalm 48

5 Threat: Kings assemble vs. Zion

6-8 Combat – victory over enemy

9 Salvation of Zion

10-12 Victory shout

13-14 Procession around the city

15 Yahweh’s universal reign

Psalm 68

A) 1-2 Combat – victory

3 Victory shout

B) 7-8 Combat of Divine Warrior (ritual

conquest)

9-10 Salvation of his people

11-14 Victory over enemy

15-18 Procession to Zion

19-20 Victory shout

C) 21 Combat – victory over enemies

22-23 Salvation of his people

24-27 Procession to sanctuary – victory

shout

28-35 Manifestation of universal reign

Psalm 77:17-21

17-19 Combat vs. sea – victory

20 Procession

21 Salvation of his people

Psalm 97

1-2 Yahweh reigns

3-5 Combat – victory over enemies

6-7 Manifestation of universal reign

8-9 Victory shout

Psalm 104

1-9 Combat – victory (creation myth)

10-30 Shalom (return to fertility – new

creation)

31-35 Victory shout

Psalm 110

1.4 Yahweh establishes his king

2 Manifestation of king’s reign

3 Procession to Zion

5-7 Combat – victory

Psalm 9

6-7 Combat – victory over enemy

8-9 Manifestation of universal reign

10-11 Salvation of his people

12-13 Victory shout

Psalm 29

3-9a Combat vs. waters- victory

9b Victory shout

10 Manifestation of universal reign

11 Shalom (abundance) of the restored order

Psalm 47

2-4 Combat – victory over enemy

5 Salvation of his people

6 Procession

7-8 Victory shout

9-10 Manifestation of universal reign

Psalm 65

6 Salvation of his people

7-8 Combat vs. seas and nations –

victory

9 Manifestation of universal reign

10-13 Shalom (return to fertility – new

creation)

Psalm 76

4-8 Combat – victory over enemies

9-10 Salvation of oppressed

11-12 Procession to brings gifts to

Yahweh

13 Manifestation of universal reign

Psalm 89

6-9 Yahweh’s universal reign

10-13 Victory over enemies

11-19 Procession – victory shout

Psalm 98

1-2 Combat – victory

3a Salvation of his people

3b Manifestation of universal reign

4-9 Procession

Psalm 106:9-13

9-10a Combat vs. sea – victory

10b Procession

11-13 Salvation of his people

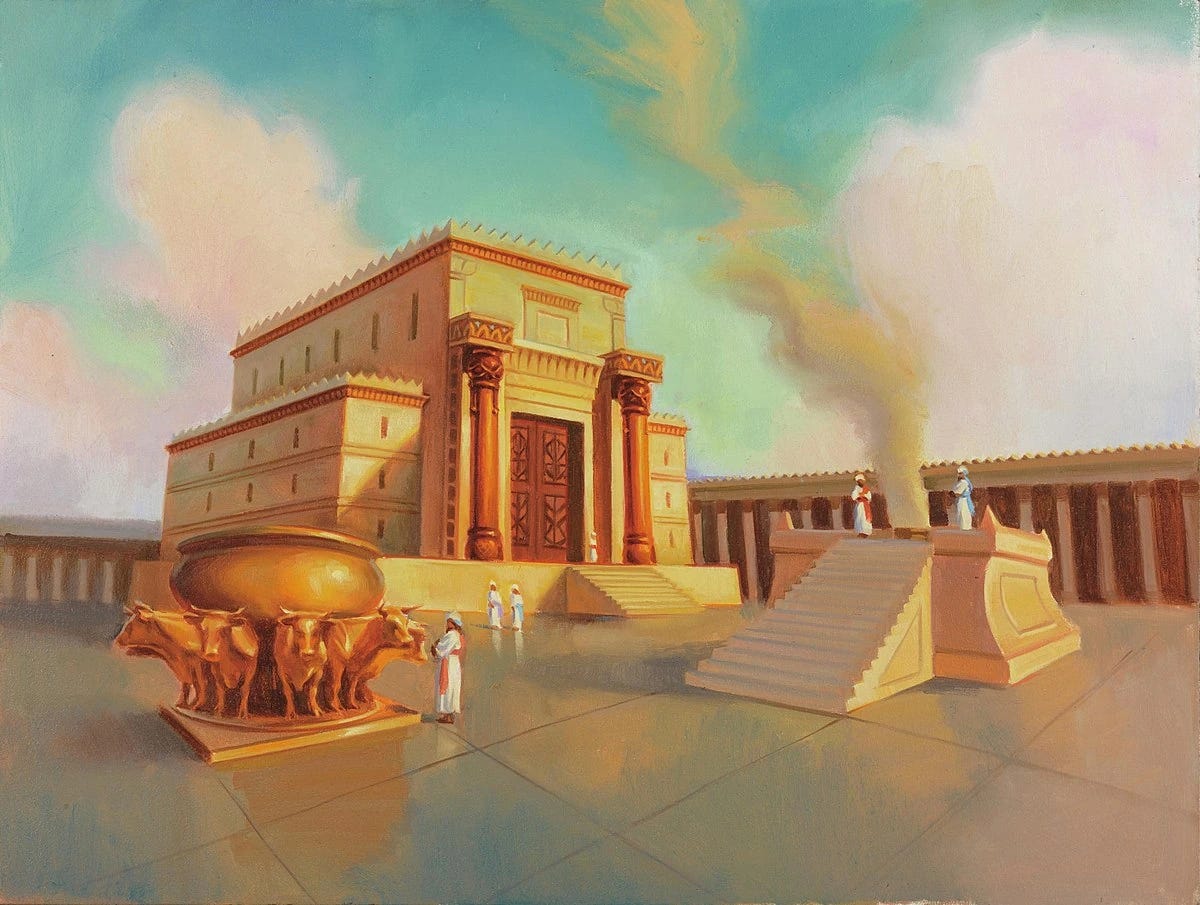

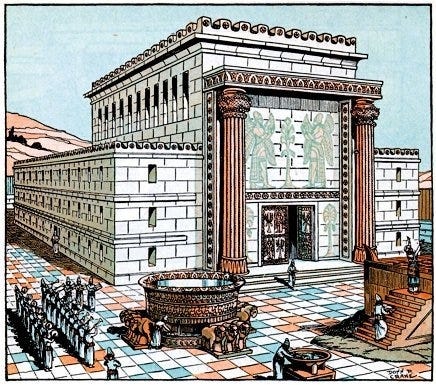

In his seminal works on the psalter,[35] Norwegian scholar Sigmund Mowinckel proposed a comprehensive interpretation for these texts. Given the psalms above, some of which comprise a subset of a distinct corpus dealing with Yahweh’s kingship (the so-called “Enthronement Psalms”),[36] Mowinckel proposed a Sitz im Leben within the liturgy of a festival similar to the Babylonian Akītu Festival or the Hittite Purulli Festival. Such would have been, for the Israelites, the Feast of Tabernacles, also called the Feast of Booths and Sukkot: Israel’s (originally New Year) harvest festival.[37] It was at this time, as the agricultural year came to its end, that infertility, death, and disorder became most salient. The forces of Chaos would assume their temporary dominance over the cosmos, and the Israelites looked to Yahweh’s autumn rains which would herald the return of fertility and life.[38] In anticipation of such rejuvenation, and akin to other ancient Near Eastern New Year festivals, the festival celebrated (and, in Eliadean terms, enacted) Yahweh’s defeat of the raging Sea and its associate Dragon,[39] as well as his victory over Death.[40]

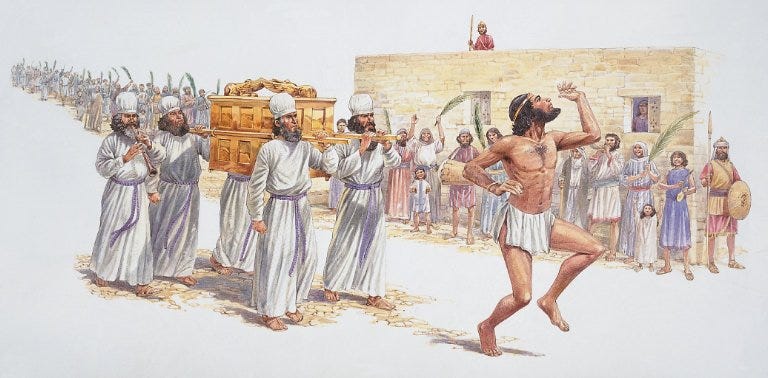

Mowinckel argued that the central cultic event of this festival was the triumphal procession of Yahweh.[41] In this procession, Yahweh—symbolized by his holy shrine, the ark—was carried amidst singing and dancing to the Temple, where the god was then ritually enthroned.[42] Such processional rituals were, as we have seen, integral parts of other ancient Near Eastern New Year festivals, while it is possible that such a ritual enthronement had also existed at Ugarit.

It is in the context of such an event that antiphonal processional hymns like Psalm 118 become clear:

There are glad songs of victory in the tents of the righteous.

“The right hand of Yahweh does valiantly…”

…Open to me the Gates of Righteousness,

that I may enter through them

and give thanks to Yahweh.

This is the Gate of Yahweh;

the righteous shall enter through it.

…Save us, we beseech you, O Yahweh!

O Yahweh, we beseech you, give us success!

Blessed is the one who comes in the name of Yahweh.

We bless you from the House of Yahweh.

Yahweh is God,

and he has given us light.

Bind the festal procession with branches,

up to the horns of the altar. (vv. 15, 19-20, 25-27)

The “victory” here alluded to is none other than Yahweh’s triumph over the forces of Chaos, celebrated as the procession makes its way to the inner gates of the Temple.[43] The “tents” were likely the ritual booths, and the branches those the Israelites cut in celebration of the Feast of Tabernacles:

On the fifteenth day of this seventh month, and lasting seven days, there shall be the Festival of Booths to Yahweh.

…On the first day you shall take the fruit of majestic trees, branches of palm trees, boughs of leafy trees, and willows of the brook; and you shall rejoice before Yahweh your God for seven days.[44]

Like the cultic icons of the gods at the other ancient New Year festivals, the ark no doubt followed along a fixed processional road, a via sacra, on its way to the Temple. Mowinckel posits that this was the mĕsillâ: the ascending “paved road” often citied in related psalms.[45] Indeed, in an article entitled “No Highway! The Outline of a Semantic Description of Mesillâ,” N. L. Tidwell provides an in-depth analysis of the nature and function of this kind of road in ancient Israel. He independently concurs that the mĕsillâ indeed acted as the processional via sacra of ancient Israel, particularly during the Feast of Tabernacles:

The Old Testament portrait of ancient Israel’s “road that ascends” consistently maintains an unbreakable bond between mesillâ and sacred sites, specifically the tabernacle/tent/Ark-sanctuary cities…In fact, the evidence suggests that the “road that ascends” to the city gate and continues beyond the gate as the main, paved route to the city’s temple was on certain festival occasions, notably at Sukkot, a significant part of a sacred way whose two termini were the temple within the city and a natural sacred site outside the city walls.[46]

Given the nature of this processional road, Tidwell draws comparisons with the processional road at Hattusa, “which extended from the sanctuary within the city to the ḫuwasi stone outside the city,” as well as with the processional road at Babylon which linked Marduk’s temple to the bīt akīti outside the city. [47] Like these other processional roads principally associated with the New Year festival, the Sacred Way in Jerusalem likely ascended from a “natural sacred site” just outside the city up to the Temple in the city proper. From this suburban site, the ark would have been processed up the Jerusalem mĕsillâ into the Temple during the New Year festival.

Again, these findings corroborate Mowinckel’s assertion that the procession to the Temple was understood as the “ascent” or “going up” to Jerusalem/the Temple, expressed in numerous psalms by the Hebrew verb ‘ālâ.[48] Likewise, Tidwell finds that

the verb most distinctly and, among the road-words of the Old Testament, uniquely associated with mesillâ is ‘ālâ; mesillâ alone, of all the biblical road words, is … the only road word which functions as the grammatical subject of ‘ālâ.[49]

So, for example, Psalm 24, which describes the cultic “ascent” to the gates of the Temple and the following antiphonal exchange between celebrants, who bear the ark and petition entry from the gate-keeper:

The earth is Yahweh’s and all that is in it,

the world, and those who live in it;

for he has founded it on the Seas,

and established it on the Rivers.

Who shall ascend (‘ālâ) the Mountain of Yahweh?

And who shall stand in his Holy Place?

Those who have clean hands and a pure heart,

who do not lift up his soul to what is false,

and do not swear deceitfully.

They shall receive blessing from Yahweh,

and vindication from the God of his salvation.

Such is the company of those who seek him,

who seek the face of the God of Jacob.

Lift up your heads, O gates!

and be lifted up, O ancient doors!

that the King of (the) glory may come in.[50]

Who is the King of (the) glory?

Yahweh, strong and mighty,

Yahweh, mighty in battle.

Lift up your heads, O gates!

and be lifted up, O ancient doors!

that the King of (the) glory may come in.

Who is this King of (the) glory?

Yahweh of Hosts,

he is the King of (the) glory.[51]

Yahweh, who is proclaimed King at the New Year festival, is here represented by his ark, which has arrived at the Temple gates and awaits cultic installation within the Holy of Holies.

Concerning the details of the processional road, its location and starting-point, Mowinckel conjectures:

On the basis of the story told in 2 Sam. 6 as to how David took Yahweh’s ark to Jerusalem, we may guess that the processional way started from a place called the house of Obed-Edom, outside the oldest part of the town, the ‘castle of David’, and from there it ran on the outside (to the east) of, or through the royal castle and into the temple court through the eastern gate…[52]

Based on a convergence of evidence given above, I posit here that the House of Obed-Edom was probably the “natural sacred site” at the starting point of the mĕsillâ. This correlation matches the comparative data well: as the ḫesti house marked the starting point of the Hittite processions, and the “Akītu house” the Babylonian processions, so the House of Obed-Edom began the Israelite processional way.

Leaving the House of Obed-Edom and traveling along this Sacred Way, Yahweh (as the ark) would then pass by the festive crowds excitedly clamoring for a glimpse at their deity. As noted in Chapter 1, it was for this reason that the New Year procession was also the premier cultic epiphany of the god. Mowinckel too argues this idea, noting that this was the time when Yahweh’s shrine was presented to be seen before all of Israel, not hidden in the darkness of the Holy of Holies. “The festival is, then,” he notes, “a festival of the epiphany of Yahweh in the literal meaning of the word.”[53] Moreover, Mowinckel argues, “It is this appearance and enthronement day of Yahweh which originally was called ‘the day of the Lord’, ‘the day of the feast of Yahweh’.”[54] The Day of the Lord is thus the same as the day of Yahweh’s procession during Sukkot—the day of his epiphany.

Finally, with much singing and dancing, the ark arrived at the Temple, where it was re-installed. This was understood as the god’s enthronement. Indeed, Yahweh was imagined as “enthroned between the Cherubim” of the ark in the Temple.[55] Like the triumphant announcement of Baal’s kingship after his defeat of Yamm, and that of Marduk before his defeat of Tiamet, Yahweh was then declared king after his defeat of Sea, Leviathan, and Death. So Enthronement Psalm 93:[56]

Yahweh has become king! he is robed in majesty;

Yahweh is robed; he is girded with strength.

He has established the world; it shall never be moved.

Your throne is established from of old;

you are from everlasting.

The Rivers have lifted up, O Yahweh,

the Rivers have lifted up their voice;

the Rivers lift up their roaring!

But mightier than the voices of many Waters,

than the waves of Sea,

is Yahweh on high.

Your decrees are very sure;

holiness befits your House,

O Yahweh, forevermore.[57]

Yahweh has become king after defeating the chaos-forces and creating the world. The chaos-waters—here “the Rivers” and “Sea,” and thus parallel to Baal’s enemies (Judge) River and Sea—opposed him, lifting up their thunderous voice in challenge to his power. But his mighty voice (thunder) is mightier than theirs, and so he rules assuredly and forevermore from his house (Temple) as king. As Baal’s voice was said to issue forth from his temple at the celebration of his enthronement, so is Yahweh’s voice praised at his.

These aspects are highlighted in Psalm 29, which many scholars maintain was originally “a Canaanite psalm taken over wholesale, with the simple substitution of the name of Yahweh instead of Baal for the deity concerned.”[58] Regardless, it too presents Yahweh enthroned after vanquishing the chaos-waters, emphasizing the power of his mighty voice:

The voice of Yahweh is over the Waters;

the God of glory thunders,

Yahweh, over many Waters.

The voice of Yahweh is powerful;

the voice of Yahweh is full of majesty.

The voice of Yahweh breaks the cedars;

Yahweh breaks the cedars of Lebanon.

He makes Lebanon skip like a calf,

and Sirion like a young wild ox.

The voice of Yahweh flashes forth flames of fire.

The voice of Yahweh shakes the wilderness;

Yahweh shakes the wilderness of Kadesh.

The voice of Yahweh causes the oaks to whirl,

and strips the forest bare;

and in his temple all say, “Glory!”

Yahweh sits enthroned over the Flood;

Yahweh sits enthroned as king forever.

May Yahweh give strength to his people!

May Yahweh bless his people with peace! (vv. 3-11)

Ingenious, comprehensive, and placing ancient Israel appropriately in its ancient Near Eastern milieu, Mowinckel’s theory has found widespread acceptance—though also its share of detractors.[59] I side with recent defenders of the theory[60] and accept the outlines of Mowinckel’s hypotheses as stated above. Indeed, as we shall see in Chapter 7, Mowinckel’s reconstruction is crucial for understanding Mark’s handling of Jesus’ ministry, particularly the triumphal entry and crucifixion, and even informs the very structuring of the gospel narrative.

Drawing all of these strands together, from traditional motifs of the combat myth to reconstructions of its crucial festival, I close this examination of the combat myth in its original ancient Israelite cultic context with a look at Psalm 68. As a liturgical text of the New Year festival, it is dense with Chaoskampf material, and includes within its cluster of imagery the mighty voice, binding, trampling, and scattering motifs; traditional epithets and descriptions of the Canaanite storm-god; allusions to the battles with Sea and Death; as well as vivid descriptions of the New Year procession to the Temple:

Let God rise up, let his enemies be scattered;

let those who hate him flee before him.

…Sing to God, sing praises to his name;

lift up a song to the Rider of the Clouds;

his name is Yahweh—

be exultant before him.

…Rain in abundance, O God, you showered abroad;

you restored your heritage when it languished;

your flock found a dwelling in it;

in your goodness, O God, you provided for the needy.

…With mighty chariotry, twice ten thousand,

thousands upon thousands,

Yahweh came from Sinai into the Holy Place.

You ascended the high Mount,

leading captives in your train

and receiving gifts from people,

even from those who rebel against Yahweh God’s abiding there.

…Our God is a God of salvation,

and to the God Yahweh belongs escape from Death.

But God will shatter the heads of his enemies,

the hairy crown of those who walk in their guilty ways.

Yahweh said, “I stifled the Serpent,

I muzzled the Deep Sea!”

…Your solemn processions are seen, O God,

the processions of my God, my King, into the Sanctuary—

the singers in front, the musicians last,

between them girls playing tambourines:

“Bless God in the great congregation,

Yahweh, O you who are of Israel’s fountain!”

There is Benjamin, the least of them, in the lead,

the princes of Judah in a body,

the princes of Zebulun, the princes of Naphtali.

Summon your might, O God;

show your strength, O God, as you have done for us before.

…Rebuke the Beasts that live among the reeds,

the herd of bulls with the calves of the peoples.

Trample under foot those who lust after tribute;

scatter the peoples who delight in war.

…O Rider in the heavens, the ancient heavens;

listen, he sends out his voice, his mighty voice.

(vv. 1, 4, 9-10, 17-18, 20-22, 24-28, 30, 33)

NEXT: DEVELOPMENTS OF THE HEBREW COMBAT MYTH

[1] ABD, “Warrior, Divine,” 876.

[2] Andrew R. Angel, Chaos and the Son of Man: The Hebrew Chaoskampf Tradition in the Period 515 BCE to 200 CE, Library of Second Temple Studies (London: T & T Clark, 2006), 25 n. 177.

[3] Frank Moore Cross, Canaanite Myth and Hebrew Epic: Essays in the History of the Religion of Israel (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1973), 140.

[4] For this translation, see Mitchell Dahood, Psalms (Garden City: Doubleday, 1966), 131. Though this reading is debated, many scholars translate this passage similarly, likewise reading the Hebrew verb šbm here. Cf. Patrick D. Miller, “Two Critical Notes on Psalm 68 and Deuteronomy 33,” HTR 57 (1964): 240, who translates, “The Lord said, ‘I muzzled the Serpent, I muzzled the Deep Sea.’” He cites Frank Moore Cross for additional authority, n. 3. For a critique of this reading, see Day, God’s Conflict, 113-19.

[5] God’s Conflict, 6.

[6] Ibid., 6, 39.

[7] For an extensive comparison, see Yahweh and the Gods and Goddesses of Canaan, Journal for the Study of the Old Testament. Supplement Series (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 2002), 185-225.

[8] Ibid., 186.

[9] Wakeman, God’s Battle with the Monster, 107.

[10] Of course, death does not always have these mythical resonances. Often in the Hebrew material death is simply the expiration of life. Like the sea, which was also understood devoid of its supernatural agency, death’s mythological overtones must be assessed contextually.

[11] W. F. Albright, “The Psalm of Habakkuk,” in Studies in Old Testament Prophecy, ed. Harold Henry Rowley (Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark, 1957), 12-13. On reading “Death” in v. 13, Albright declares in note oo on 17: “The θάνατον of [the LXX] is obviously original, as seen by Cassuto, Annuario di Studi Ebraici, loc. cit.” Wakeman, God’s Battle with the Monster, 108, seems to accept Albright’s translation, but notes, “Should this reading be accepted, it would be the only direct reference to a conflict between Yahweh and Mot.” Day, Yahweh and the Gods and Goddesses of Canaan, 192, rejects it, positing that “nothing in the text previously has led one to expect that ‘death’ is actually the name of the enemy. How exactly the verse should be translated is uncertain.” However, as we have seen, the text is brimming with Chaoskampf imagery, as Yahweh’s battles with Sea and River are recalled. Even the Sun and Moon appear with their mythological associations here. Thus the context certainly suggests a mythological interpretation of Death as the final enemy in the Canaanite combat myth. Moreover, Day admittedly cannot provide a better, alternative translation.

[12] Albright, “The Psalm of Habakkuk,” 17 n. qq.

[13] See, e.g., Is 14:12; 1 Sam 28:13; Ps 71:20, 143:6; and Job 4:23, 15:29. See Wakeman, God’s Battle with the Monster, 108.

[14] The trampling of Death may also be at work in Micah 1:3: “For lo, Yahweh is coming out of his Place, and will come down and tread upon the back of the Earth,” though the broader context of the verse makes this interpretation dubious. However, the idea that Yahweh would come forth from his Temple to battle the forces of Chaos is entirely in keeping with the primary cultic context which celebrated his victories over the chaos-monsters: the New Year festival. This shall be considered in greater depth below.

[15] Wakeman, God’s Battle with the Monster, 106-17.

[16] Smith, The Ugaritic Baal Cycle Vol. 1, 63.

[17] Ibid., 97.

[18] See the analysis of Day, Yahweh and the Gods and Goddesses of Canaan, 186.

[19] For example, in 1 Cor 15 and Rom 5.

[20] Such a myth would also explain other biblical authors’ more subtle allusions to Yahweh’s battles with Death. See e.g., Alan J. Hauser, “Yahweh Versus Death: The Real Struggle in 1 Kings 17-19,” in From Carmel to Horeb: Elijah in Crisis, ed. Alan J. Hauser and Russell Inman Gregory (Sheffield: Almond Press, 1990), 11-83.

[21] Clifford, “The Roots of Apocalypticism,” 17, 19; cf. Hamblin, Warfare in the Ancient Near East, 122.

[22] See Smith, The Ugaritic Baal Cycle Vol. 1, 87-96.

[23] Ibid., 108.

[24] Ibid., 108.

[25] Quoted in Ibid., 108; emphases mine.

[26] Clifford, “The Roots of Apocalypticism,” 29.

[27] Smith, The Ugaritic Baal Cycle Vol. 1, 109.

[28] For an intriguing view on apocalypticism’s development in light of the evolving dynamic between myth and history in ancient Israel (and, briefly, the combat myth), see Paul Hanson, “Jewish Apocalyptic against Its Near Eastern Environment,” RB 78 (1971): 31-58.

[29] Clifford, “The Roots of Apocalypticism,” 31-32.

[30] For the dating of Exodus 15, see Cross, Canaanite Myth and Hebrew Epic, 121-3. Cross calls it “one of the oldest compositions preserved in biblical sources” and suggests a “tenth-century date or earlier for its being put first into writing,” 123.

[31] For a more extensive treatment of Exodus 15 and the combat myth see ibid., 112-144.

[32] Hanson, “Jewish Apocalyptic against Its Near Eastern Environment,” 43.

[33] Hanson, The Dawn of Apocalyptic, 304.

[34] Ibid., 305.

[35] Sigmund Mowinckel, Psalmenstudien, 6 vols. (Oslo: J. Dybwad, 1921-1924), vol. 2 = The Psalms in Israel’s Worship, 106-92.

[36] Pss 47, 93, 95, 96, 97, 98, 99, 100.

[37] Sigmund Mowinckel, He That Cometh (New York: Abingdon Press, 1956), 131-45; The Psalms in Israel’s Worship, 106-192.

[38] The Psalms in Israel’s Worship, 130, 134-5, 163-4.

[39] Ibid., 108, 135, 143-6, 167.

[40] Ibid., 152.

[41] As the above list shows, the procession was an important element in the Divine Warrior Hymns, no doubt reflecting their cultic setting.

[42] Mowinckel, The Psalms in Israel’s Worship, 115, 130, 170-82.

[43] Ibid., 180-2.

[44] Lev 23:34, 40.

[45] Mowinckel, The Psalms in Israel’s Worship, 171.

[46] N. L. Tidwell, “No Highway! The Outline of a Semantic Description of Mesillâ,” VT 45 (1995): 263; emphasis mine.

[47] Ibid., 263-4.

[48] This phrase thus has a specifically cultic meaning, as the “Songs of Ascent” (Psalms 120-34) reflect. See Mowinckel, The Psalms in Israel’s Worship, 171 n. 171.

[49] Tidwell, “No Highway,” 259-60.

[50] The “glory” (kbôd) of Yahweh is explicitly associated with the ark in 1 Sam 4:21-22.

[51] Frank Moore Cross also suggests that this “psalm is an antiphonal liturgy used in the autumn festival. The portion of the psalm in verses 7-10 had its origin in the procession of the ark to the sanctuary at its founding… On this there can be little disagreement.” He also points out the psalm’s connection with the combat myth, noting, “We may see reflected in this liturgy the reenactment of the victory of Yahweh in the primordial battle and his enthronement in the divine assembly or, better, in his newly built (cosmic) temple.” See Cross, Canaanite Myth and Hebrew Epic, 93. Later, he notes the similarity between the festal shout, “Lift up, O Gates, your heads!” and the triumphant shout of Baal after defeating Yamm in the Ugaritic texts, “Lift up, O Gods, your heads!” (97-99).

[52] Mowinckel, The Psalms in Israel’s Worship, 171.

[53] Ibid., 119; emphasis mine. Earlier, he writes that “the fundamental thought in the festal experience and the festal myth is that Yahweh is coming…and ‘revealing himself’, ‘becoming revealed’ and ‘making himself known’… This is not a mere idea, it is reality, visibly expressed through the symbols and rites of the feast… The festival, in short, is the festal epiphany of Yahweh,” 142.

[54] Ibid., 116.

[55] 1 Sam 4:4; 2 Sam 6:2; 2 Kings 19:15; 1 Chron 13:6; Ps 80:1; Ps 99:1; Is 37:16.

[56] Mowinckel, The Psalms in Israel’s Worship, 144-5.

[57] Following Mowinckel’s interpretation of “Yahweh mālakh.” Cf. Ibid., 107-9.

[58] Cross, Canaanite Myth and Hebrew Epic, 151-152; Day, God’s Conflict, 60.

[59] A survey of the scholarly debate is provided by J. J. M. Roberts, “Mowinckel’s Enthronement Festival: A Review,” in The Book of Psalms: Composition and Reception, ed. Peter W. Flint, et al. (Leiden: Brill, 2005), 97-115. Miller draws on J. J. Stamm’s extensive survey of Psalms research up to 1955 and notes that “Mowinckel’s theory was accepted, even if with some reservations, by [F. M. Th.] Böhl, [Johannes] Pedersen, [Aage] Bentzen, [Ivan] Engnell, [Aubrey R.] Johnson, and [Geo] Widengren” and counts “[Paul] Humbert, [Elmer A.] Leslie, and [Gerhard] von Rad among those who accepted some form of Mowinckel’s enthronement festival.” However, “it was rejected, but with hardly any argument, by [Jean] Calès, [Heinrich] Herkenne, [Edward J.] Kissane, [Friedrich] Nötscher, [Emanuel] Podechard, [Alphons] Shulz, [Raymond J.] Tournay, [W. Emery] Barnes, [Bernardus Dirks] Eerdmans, [Otto] Eissfeldt, [Johnnes] de Groot, [Robert Henry] Pfeiffer, [Ernst] Sellin-Rost, and [Moses] Buttenweiser. The only scholars to make a sustained argument against Mowinckel’s reconstruction were [Lásvló István] Pap, [Norman H.] Snaith, [Sverre] Aalen, and [Hans-Joachim] Kraus, and of those, according to Stamm, the only one to make a persuasive case was Krause” (101-4); emphasis mine. However, Miller then states, “One may question whether Kraus has made a persuasive case” (104). Cf. Johann J. Stamm, “Ein Vierteljahrhundert Psalmenforschung,” Theologische Rundschau 23 (1955): 1-68. For a similarly sympathetic overview of the debate, see Ben C. Ollenburger, Zion, the City of the Great King: A Theological Symbol of the Jerusalem Cult, Journal for the Study of the Old Testament Supplement Series (Sheffield, England: JSOT Press, 1987), 22-33. More recently, a sustained critique has been offered in Allan Rosengren Petersen, The Royal God: Enthronement Festivals in Ancient Israel and Ugarit? Ibid. (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1998). This is presented almost as a general indictment of the entire Myth-and-Ritual School’s methods, and is ultimately unpersuasive. Indeed, Miller posits that the recent lack of consensus about Mowinckel’s view owes more to shifting interests of the field than to any successful counter-argumentation, 109.

[60] Day, God’s Conflict, 18-38, 123-4, 180ff, 165, and reaffirmed in Yahweh and the Gods and Goddesses of Canaan, 100; Patrick D. Miller, “Israelite Religion,” in The Hebrew Bible and Its Modern Interpreters, ed. Douglas A. Knight and Gene M. Tucker (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1985), 220-22; John Gray, The Biblical Doctrine of the Reign of God (T & T Clark, 2000); and Roberts, “Enthronement Festival,”113.