God's Fight with the Dragon, Part I

The Roots of the Devil and the End Times in Ancient Near Eastern Myth

It may come as a shock to learn that the most important story about God in ancient Israelite religion was the one in which he battles a draconic sea monster using his lightning bolts and mighty storm winds. Most people will not even know such a story existed, let alone that it formed the core of ancient Temple worship, or that it was the basis for the later invention of the Devil in Christian mythology. But, if we’re to understand the history of apocalyptic thought, and early Christianity specifically, we must consider the crucial role played by this ancient myth and its various transformations throughout history. That is what I attempted in my book The Combat Myth According to Mark: From Ancient Near Eastern Genre to Apocalyptic Gospel, which I began as an undergraduate thesis and finished while assisting one of my professors at the Albright Institute of Archeological Research in Jerusalem a little over ten years ago. Using methods of comparative mythology, I attempted to track the evolution of the “combat myth” from ancient near eastern cultic traditions into ancient Israelite religion, Jewish apocalypticism, and, finally, the early Christian church. Those familiar with the dragon tale from the work of Joseph Campbell, Erich Neumann, and Jordan Peterson will perhaps be intrigued to learn just how fundamental this myth truly is—and how it is still shaping the religious psyche today.

This series is posted as part of an ongoing effort of mine to showcase the novel insights introduced by the modern historical-critical perspective on the Bible. Any form of metamodern Christianity worth the name must take this perspective seriously, I believe, even as it transcends its limited frame for something more comprehensive.

The Combat Myth Genre

In Genesis 1, Creation is presented as a series of differentiations, each one more minute than the last, until our own familiar world is, as it were, whittled into being from the formless, cosmic tohu wa-bohu. So God makes Order out of Chaos, and sense out of confusion—a process of paramount importance to human communities from the creation of Genesis to today. Indeed, to compare great things with small, the modern scholar engages in a similar task when approaching the disparate, sometimes bewildering, but ever fascinating texts which have come down to us from the ancient Near East. To make sense of them likewise requires differentiation: separating similar sorts from the whole, and forming categories of like types. When we do so, the dizzying blur is focused somewhat and we can see, if only a bit more clearly, through the eyes of the peoples who produced them.

The genre of “combat myth” is one such type or category, into which scholars place those ancient stories sharing the same basic plot of battle between two supernatural adversaries.[1] In rudimentary terms, such myths narrate a god’s fight with a monstrous villain who threatens order and life in the cosmos. The champion “divine warrior” is invariably the storm-god, while his destructive adversary typically takes the form of a dragon or sea monster. After a struggle for dominance in which the dragon initially proves victorious, the divine warrior ultimately vanquishes his foe, thereby ensuring order and fertility in the cosmos. For this he is granted kingship and, his triumph festively celebrated, the storm-god processes to his newly-constructed palace (i.e., temple) for enthronement as king.

Versions of this myth are attested throughout the ancient Near East in Egyptian, Sumerian, Babylonian, Ugaritic, Hurro-Hittite, Assyrian, and Israelite texts. To the west, its variations appear in such Greek tales as the battle of Zeus with Typhon, and Apollo with Python;[2] further east, it underlies the Indian tale of Indra’s battle with Vritra.[3] This attestation across such vast expanses of geography, time, and culture suggests that, to many ancient peoples, the myth maintained a considerable importance. However, to appreciate this significance we must more fully understand the myth itself.

Of course interpreting such myths in any definitive sense is impossible; they are multivalent stories with resonances in various semantic registers (some of which have no doubt been lost to history). Nevertheless, from our vantage point, the combat myth does seem to have at its core one appreciable, overarching concern, whose fundamental importance to human life helps to explain its broad popularity. That concern is order itself: where it comes from, how to maintain it, and what to do when it goes away. Viewed in this light, the enduring popularity of the combat myth would have owed largely to its success at providing a means by which ancient peoples could make sense of their world—to know why and how the world was structured. Thus Richard J. Clifford astutely notes that

the combat myth was a customary ancient way of thinking about the world. Ancient Near Eastern “philosophical” thinking was normally done through narrative. …To do philosophy, theology, and political theory, modern thinkers employ the genre of the discursive essay rather than the narrative of the combat myth. Despite the differences, one should not forget that ancients and moderns share an interest in ultimate causes and both are intent on explaining the cosmos, the nature of evil, and the validity and the functions of basic institutions.[4]

Once one appreciates this fundamental concern with the establishment of order, the combat myth’s specific relationship to 1) agricultural, 2) cultic, 3) political, and 4) philosophical/theological aspects of life in the ancient Near East becomes more clear. Examining these diverse yet interrelated realms of experience reveals an equally complex set of semantic interrelationships, all of which bear heavily on the present study:

1) Agricultural. An interpretation with nearly universal acceptance among scholars holds that most combat myths reflect the transitions of the agricultural calendar, its narrative progression mirroring seasonal changes and their effect on fertility. In this sense, the divine warrior is principally the god of the storm and rainfall, and thus the bringer of fertility, sustenance, and life itself. Conversely, the enemy of the divine warrior represents sterility and death: the forces of destruction and Chaos embodied as a monstrous creature such as a dragon or serpentine beast. Every year these cosmic forces—fertility/sterility, the growing season/the barren summer—battle for supremacy. The lack of rain and relative dearth of summer signaled the temporary victory of the chaos-monster, but fall rejuvenation heralded the ultimate success of the storm-god, whose autumnal rains then came to revive the land yet again.

This agricultural interpretation provides perhaps the most basic and obvious sense of the combat myth—one whose universal significance would in itself justify the broad popularity of the narrative in the ancient world. The order of the seasons—so important to agricultural societies—is explained, its origin made clear, and assurance given that, even in the harsh dearth of the barren season, life will spring again; such is the order of things.

2) Cultic. Linking the mythic narrative to agricultural realities allows us to appreciate the actual material contexts of the myths themselves, since most seem to have had a cultic Sitz im Leben at a (usually springtime) New Year festival. As a celebration of new life and the return of fertility, it is not surprising that such a setting occasioned the myth’s chief cultic realization (given the basic agricultural interpretation just considered).

Yet the relationship of the combat myth to the New Year is still more fundamental. Indeed, because the combat myth is essentially about order and the imposition of order onto Chaos, the creative act lies at the heart of the myth. For this reason, the combat myth is often a cosmogony, the victory of the divine warrior resulting in the actual Creation of the world. Since Creation provided the paradigmatic model for the New Year festival—the “Beginning” as archetype for the new beginning—the role of the combat myth at the festival is further elucidated.

However, to say that Creation provided the archetype for the New Year is not to suggest that the first was a kind of metaphor for the second, or that the New Year was somehow “modeled” on Creation. Rather, the New Year was Creation: each New Year was a new Creation. As Mircea Eliade has shown, ritual activity in ancient religious cult did not merely recall sacred deeds of the primordial past—it re-created them. Thus, ancient Near Eastern New Year festivals were celebrated as a return to the beginning of time itself; indeed, each New Year was a re-Creation of the cosmos. This “eternal return” helps to explain one chief concern of ancient New Year ceremonies: purification. Eliade writes:

Since the New Year is a reactualization of the cosmogony, it implies starting time over again at its beginning, that is, restoration of the primordial time, the “pure” time, that existed at the moment of Creation. This is why the New Year is the occasion for “purifications,” for the expulsion of sins, of demons, or merely of a scapegoat. For it is not a matter merely of a certain temporal interval coming to its end and the beginning of another (as a modern man, for example, thinks); it is also a matter of abolishing the past year and past time. Indeed, this is the meaning of ritual purifications…[5]

This semantic association of the New Year with renewal, re-purification, forgiveness of sins, and ablution is critical, and I shall note particular examples as they appear. In terms of specific rites, however, the notion that these festivals were fundamentally re-creations and not simply recollections or commemorations elucidates why the combat itself is thought to have been ritually reenacted at such New Year festivals, as well as why the texts of these myths were recited as part of the celebrations. Through these enactments, participants in the cult actually helped facilitate the new Creation.

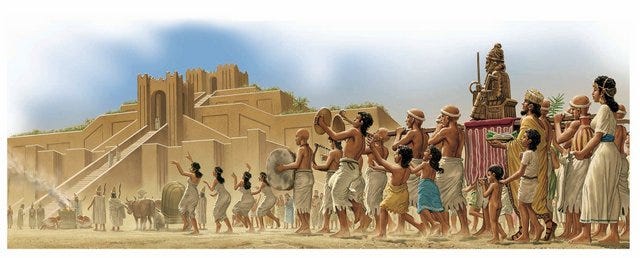

Eliade’s notion of eternal return may also shed light on the key cultic activity of these ancient Near Eastern New Year festivals. For central to all was the festal procession of the storm-god’s idol, which was taken from its temple and ceremonially paraded with majestic pomp and fanfare before the people as it traveled to some different cultic site(s). Since sheltered for the rest of the year within its holy precincts, out of sight, this was the god’s chief presentation before the people—that is, his chief epiphany. The New Year was the time when the god revealed himself in all his glory. So Eliade:

Symbolically, man became contemporary with the cosmogony, he was present at the creation of the world. In the ancient Near East, he even participated actively in its creation (cf. the two opposed groups, representing the god and the marine monster). It is easy to understand why the memory of that marvelous time haunted religious man, why he periodically sought to return to it. In illo tempore the gods had displayed their greatest powers. The cosmogony is the supreme divine manifestation, the paradigmatic act of strength, superabundance, and creativity.[6]

The presentation of the deity concluded, the god returned through the city gates to his great temple in the main city. With the reinstallation of the idol, the cultic rites of the New Year festival were essentially concluded.

In the interaction of myth and ritual, the orderly cycle of Nature’s seasonal changes has its counterpart in the human realm of religious rite, each one dialectally informing the other: myths about order are actively embodied as actions which give a sense of order to human life. Patterned behavior and religious time impose order on the bewildering Chaos of personal experience and, as players in the cosmic drama, human beings themselves help facilitate rejuvenation of the cosmos through ritual.

3) Political. On the level of human communities, social hierarchy and institutions were structural givens of ancient life in need of explanation as much as those of the natural world. In practical terms, the maintenance of social order required strong political leadership, and in the ancient Near East it was the king who filled this vital role—a position of immense social, cultic, and even philosophical importance. For this reason kingship is a central concern in nearly all combat myths. The divine warrior, consequent to his mighty deeds, is granted kingship over the cosmos, and a palace is built for him (the palace of the god being in fact his temple: the god’s abode on earth).

Though, since divine kingship was itself a reflection of earthly practices and perceptions of kingship, historical/political realities also played a role in various combat myths. As the god’s representative on earth, the human king was also associated with the storm-god’s battles against the negative forces of Chaos and destruction. The king’s battles with his earthly enemies mirrored the god’s battles with his supernatural enemies. On this level, then, combat myths had clear political and historical overtones; myth and history informed one another.

4) Philosophical/Theological. Finally, seeing the combat myth as a vehicle for “philosophical” or “theological” thinking allows us to consider broader ways in which the myth articulates assumptions about the nature of the world, and what kinds of conclusions its draws. When we do so, a particular worldview emerges—one which, though realistic about the struggles and trials of life, is ultimately optimistic about the underlying workings of the cosmos. The divine warrior is a god of order, while the dragon represents all that is destructive and disorderly—that is, Chaos. Because of this dichotomous conflict, the combat myth is often referred to as the myth of Chaoskampf: the battle with Chaos. But Chaos is defeated (if only cyclically), which in itself seems to assert a basic confidence in the life-affirming workings of the cosmos, thus offering hope in times of death, dearth, and loss.

The god of order and fertility is the rightful king, whose power was both theologically important (i.e., indicative of/justifying the god’s central place in the pantheon) but also of a broader “philosophical” significance. That the divine warrior is proclaimed king entails more than just neat narrative closure to such myths. Rather, it says something about the cosmos: the good god of order and fertility is in control. He is powerful over the forces of Chaos; he can defeat them, and has. In the ever-uncertain lives of men and women in the ancient world—so much at the whim of death, disease, war, and a host of other uncontrollable forces—such narratives no doubt provided a sense of reassurance and stability. Though the fields go barren and chaotic forces take hold of the world for a time, the god of order and prosperity is in charge; he is king.

Additionally, the association of the combat myth and purification outlined earlier should also be considered in light of its broader philosophical implications. In a similar way to the existential threats just cited, spiritual degradation and corruption no doubt presented their own anxieties. Impurities resulting from moral and/or ritual failures, personal or public, required purgation. With the return to the pure, original state of the cosmos, the New Year offered fresh assurance of a clean slate. Thus, by extension, the victory of the storm-god and the defeat of Chaos could inspire private, psychological comfort in addition to general, philosophical confidence.

All of these aspects of the combat myth form a complex of interrelated themes. Rejuvenation, divinity, kingship, and justice interweave in a rich tapestry of association—each informing the other, each but one element in a broader, holistic worldview. The totality, however, is best understood as one cosmic myth of order.

Having considered the crucial themes and associations common to all ancient Near Eastern combat myths, our task now turns to examining the common structure they share. However, Clifford cautions, “One must be careful methodologically about describing the elements of the genre of combat myth in the ancient Near East. There is no ideal form of the myth but only diverse realizations.”[7] Unique elements in any regional combat myth should not be looked upon as divergences from some pure and original form; each version of the myth reflects the specific concerns of the people telling it.[8] Though, given this important caveat, Clifford does ultimately conclude that “a consistent plot line can be abstracted.”[9] Indeed, some useful attempts have already been made at outlining the basic plot of the combat myth and abstracting its core narrative elements.

The first major attempt to do so was put forth by Joseph Fontenrose in his comprehensive study of ancient combat myths.[10] His outline proved a crucial first step, though not without its flaws (as subsequent critique by Neil Forsyth has demonstrated).[11] Forsyth subsequently proposed an alternative schema, applying to the combat myth those narrative functions developed by the Russian Formalist Vladimir Propp.[12] His schema identifies the following fundamental narrative elements:

1. Lack/Villainy 2. Hero emerges/prepares to act 3. Donor/Consultation 4. Journey 5. Battle 6. Defeat 7. Enemy ascendant 8. Hero recovers 9. Battle rejoined 10. Victory 11. Enemy punished 12. Triumph

Thus the conflict begins with an initial dilemma: (1) A monstrous villain poses a challenge. (2) The heroic warrior god appears to meet this challenge. (3) At this point, he may be aided by some counsel, a “donor” supplying him with either a helpful gift or merely some important advice. (4) The storm-god sets out on his mission. (5) The battle ensues, usually with (6) the god’s initial defeat by the monster. Consequently, (7) the monster’s power and strength increase. However (8) the god soon recovers from his initial defeat and (9) the second round of the cosmic battle ensues. (10) This time the god is victorious and (11) he punishes the monster (usually by mutilating the corpse in some way). (12) Finally, the storm-god exults in a triumphant celebration, such as a feast or glorious procession (thus reflecting the cultic New Year setting). Forsyth notes that some of these elements are always present in combat myths (e.g., Villainy, Battle, Victory) “for without them the narrative would not be a combat,” but adds that “others may at times be absent or attenuated without changing the basic structure and character of the narrative.”[13] Though not without its own flaws, Forsyth’s narrative schema is helpful for providing a consistent framework for the genre, and I shall adopt it in this monograph.[14]

Having thus considered the myth’s basic themes and structure, a few specific motifs warrant attention, since certain motifs and images reoccur in different combat myth traditions with a regularity suggestive of generic composition. Indeed, since these are often employed outside of a strictly narrative context (particularly in later texts, whose allusions assume familiarity with the myth), their recognition can be crucial for appreciating less explicit applications of the Chaoskampf myth.

The most important of these include the following: (1) Because the hero is god of the storm, anthropomorphized meteorological phenomena provide common images: thus the winds are his chariot, lightning-bolts are his arrows, and, most importantly, thunder is his battle cry or mighty voice. At the sound of his mighty voice, the storm-god’s enemies quake, flee, or submit. (2) Whether in the context of battle or punishment, binding of the enemy is a recurrent topos, either with a rope or, more specifically, a muzzle. (3) After defeating the chaos-monster, trampling of the body, or any form of stepping/stomping/standing upon the body are common punishments (thus humiliating the victim, and exalting the victor). (4) So too is a) dividing/dismembering the body, which is usually followed by b) scattering of the corpse. Though distinct actions, the latter requires the former to have first taken place, and so I consider these as two parts of the same motif.

While many of these actions no doubt reflect common features of actual battle in the ancient world, in myths of combat they become essentially formulaic deeds of the victorious storm-god, with a regularity typical of generic composition. Still, one must be cautious about positing allusions to the combat myth based on such imagery. Imagery alone is rarely enough to establish a connection; obviously not every instance of binding or trampling recalls the myth of Chaoskampf. However, one is on sounder ground certainly the more such motifs are found together, while a true convergence of themes, structure, and imagery will provide the strongest case for arguing a text’s dependence on the combat myth.

Finally, with regard to the history of the combat myth pattern, we find that its origins, transmission, and influence are complex and fairly unclear. Fortunately, however, these considerations are not relevant to the present study since we are not attempting any kind of in-depth history of the ancient Near Eastern combat myth genre. Rather, our interests are limited to that’s genre’s application in one text of the first century CE, the Gospel of Mark. The following survey of select combat myths from the ancient Near East is meant therefore only to flesh out the above narrative schema and highlight the recurrent themes and motifs so that one can recognize their ultimate presence in the Gospel of Mark. Accepting a genetic relationship of these texts while ignoring more complicated issues of origin and lines of dependence, the following survey is organized more or less chronologically[15]—a presentation which may obfuscate the complexity of transmission history, but nonetheless allows for a general sense of evolution. To these specific examples of the combat myth we now turn.

Ninurta vs. Azag

Perhaps the oldest extant combat myth from the ancient Near East is the Sumerian text Lugal-e, which describes the battle between Ninurta (god of the thunderstorm and fertility) and the dragon Azag. The version we possess was originally composed around 2150 BCE.[16] The conflict begins as Ninurta sits on his throne at feast. Sharur, his trusty battle mace (which acts as an independent agent in the story), enters and informs him of a terrible and unprecedented new threat: the “fearless warrior, Azag,” who was “nursed by wild beasts.”[17] This Azag has spawned a host of evil helpers—the Stone Things, which serve the villain as an army of warriors—and has been treacherously proclaimed king over the highland by the plants there. Sharur warns Ninurta that Azag now seeks a decisive confrontation:

It has given instructions concerning you for an encounter,

Warrior, there have been consultations with a view to taking away your

kingship.

…It is slapping faces, relocating dwelling-places,

Daily the Azag is turning the border (district) over to its side![18]

Thus roused to action by this encroaching threat, Ninurta sets off to battle the rebellious beast. He mounts his storm-chariot, riding the seven gales and casting a tempest in front of him as he hurries onward. As he drives, he slaughters countless couriers of the enemy, and victories over various draconic and serpentine beasts are recalled:

O Ninurta, may the names of the warriors slain by you be mentioned:

The Kulianna, the Basilisk, the Gypsum…

…the Thunderbird, and the “Seven-headed Serpent”

you verily slew, (o) Ninurta, in the highland.[19]

Though successful against the helpers of the enemy, perhaps even trampling them all before him,[20] Ninurta is eventually cautioned by Sharur not to attack Azag. Ninurta disregards Sharur’s counsel, however, and as the sun stops and darkness covers the earth he confronts the dragon:

The Azag rose to attack in the front line of the battle,

The sky it pulled down as a weapon for its hip, took it in hand,

into the earth it struck the head snakelike…

The Azag was going to crash like a wall (down) on Ninurta, Enlil’s son;

as were it a day of doom, it screamed wrathfully,

like a formidable serpent, it hissed from among its people…[21]

Against Ninurta’s attack, Azag raises a dust storm and thereby defeats the overconfident storm-god. The divine warrior overcome, Sharur flees to Enlil for counsel in the matter, where he learns that Enlil will muster a rainstorm to clear the dust that Azag is raising. Enlil does just this, and Ninurta—no longer choked by the dust—is able to vanquish the dragon. In a rage, Ninurta sends forth his battle cry and tramples Azag, then dismembers/divides its body. This done, he then “scattered it over the mountain” and “strewed it like flour.”[22]

After thus vanquishing Azag, Ninurta then judges its helpers, the Stone Things, turning them into a massive irrigation system by heaping up large quantities of the rocks. Each receives a unique punishment or reward, depending on whether or not it defected to his side. Where dispersed lakes had formed on mountaintops, he now builds dams to combine their waters and direct them down from the mountaintops to water the fields. So his combat results in a fertilizing, creative, and order-bringing act, whereas before the forces of Chaos had threatened to encroach and destroy. After this, Ninurta makes his way to his barge which, piled with riches, then festively processes down the waters to songs and praise. Finally, for all of his accomplishments, Enlil affirms the kingship of Ninurta, and the gods praise his kingly glory.

This text is exemplary of the combat myth as outlined above. The usual themes are prominent: Ninurta must defend his just and orderly kingship from the would-be usurper dragon. The storm-god’s victory results in greater order in the cosmos, both because the depredations of Azag have been neutralized, but also because the battle itself leads to an act of creation. Moreover, all of this is connected with the agricultural calendar, as the summer dust winds of Azag are defeated and Ninurta’s irrigation system waters the fields. The barren season is over and the abundance of the growing time begins.

All the imagery typical of the combat myth is likewise employed here. We see the god’s mighty voice in the form of his battle cry, as well as the trampling of the enemy, the dividing/scattering of its body, and even the binding of the Stone Things.

In its basic elements, the narrative rather neatly fits Forsyth’s combat myth schema: (1) Lack/Villainy: The dragon Azag has arisen and challenges Ninurta’s kingship, hoping to usurp the throne of the storm-god himself. (2) Hero emerges/prepares to act: Ninurta hears of this threat and is compelled to battle the beast. (3) Donor/Consultation: Sharur counsels Ninurta on the danger and strength of his foe. (4) Journey: Ninurta rides forth on storm clouds to fight Azag. (5) Battle: The two foes meet; Ninurta attacks, but Azag raises a giant dust storm in counter-attack. (6) Defeat: The dust storm overwhelms Ninurta. (7) Enemy ascendant: Consequently, Azag appears victorious in his rebellion. (8) Hero recovers: Sharur goes to Enlil, however, from whom he secures assistance.[23] (9) Battle rejoined: With the aid of Enlil’s rainstorm, the battle begins anew. (10) Victory: This time, Ninurta is victorious, and he slays Azag. (11) Enemy Punished: In a rage, Ninurta sounds his battle cry and tears the Azag apart, then scatters the body over the mountains. (12) Triumph: Ninurta festively processes down the waters in his barge. His kingship is asserted and his power is again uncontested as a result of his victory.

As intimated above, this final event, the procession of the god, reflects cultic practices—perhaps even a festal event specific to this very myth (though in this instance we cannot be certain). William Hamblin observes that Ninurta’s battle here represents an ideal form of warfare in the ancient Near East, and that such a triumphal procession would have taken place after the defeat of an historical enemy. The “Hymn to Innana,” he says, provides evidence of such, whose text describes a triumphal procession complete with music from tambourines and lyres.[24] Generally, procession of a god’s idol from one cultic site to another was a phenomenon practiced in the ancient Near East, sometimes by barge (as in Egypt), and it seems likely that this text reflects just such a cultic procession. Moreover, given the agricultural underpinnings of the myth, it is very plausible that it was associated with a seasonal festival celebrating the triumph of fertility (Ninurta) over barrenness and Chaos (Azag).

Ninurta vs. Anzu

Ninurta is the hero of another extant, though incomplete, combat myth. In this myth, the storm-god battles the monster Anzu: a composite beast with lion- and bird-like features. This Anzu has been appointed the guardian of the chief god Enlil’s chambers—chambers which house the Tablet of Destinies: a sacred tablet which confers on its possessor the authority to rule over the cosmos. After being entrusted with guarding it, Anzu comes to covet the Tablet and dreams of usurping power:

The exercise of his Enlilship his eyes view.

The crown of his sovereignty, the robe of his godhead.

His divine Tablet of Destinies Anzu views constantly.

As he views constantly the father of the gods, the god of Duranki,

The removal of Enlilship he conceives in his heart.

“I will take the divine Tablet of Destinies, I,

And the decrees of the gods I will rule![25]

Finally, seizing the opportunity while Enlil is disrobed and bathing in the holy waters, Anzu steals the Tablet of Destinies and flies away to his mountain. With the Tablet controlling the Norms of the cosmos now under the control of the monster Anzu, order is destroyed and Chaos assumes dominance over the cosmos.

Ultimately, the task falls to Ninurta to battle the beast, retrieve the Norms, and thereby reassert order. His mother Mami counsels Ninurta, advising him to use the powers of the storm to subdue Anzu and then slit his throat. Then,

When the hero heard the speech of his mother,

He was wroth, he raged (and) departed for [Anzu’s] mountain.

My lord hitched the Seven-of-Battle,

The hero hitched the seven ill winds,

The seven whirlwinds which stir up the dust,

He launched a terrifying war, a fierce conflict.

While the gale at his side shrieked for strife,

Anzu and Ninurta met on the mountainside.[26]

The two then battle one another in single combat as darkness overtakes the mountain. Ninurta unloads the power of the storm on Anzu, then fires an arrow at the beast. But his arrows prove ineffective so long as Anzu has the Tablet. Temporarily defeated, Ninurta has the god Hadad report his failure to Ea, the trickster god, in hope of some assistance. As a result, Ea provides Ninurta with a plan to use the South Wind against Anzu’s wings; after this, he is to cut them, then slit the beast’s throat. Unfortunately, the remainder of the text is too fragmentary to say precisely what follows. However, it is clear that Anzu is defeated, his throat slit (presumably by Ninurta), and order reinstated with the reacquisition of the Tablet of Destinies.

Again, themes and motifs common to the combat myth reappear. The central concern is again kingship. When Anzu steals the Tablet of Destinies, he has effectively usurped Enlil’s kingship over the cosmos. The good god of order has been defeated by a monstrous beast of disorder. Now, Ninurta must go forth to battle Anzu. To do so, he employs all of his meteorological weaponry.

Plot-wise, this story also fits well the combat myth schema: (1) Lack/Villainy: The chaos-monster Anzu steals the Tablet of Destinies. (2) Hero emerges/prepares to act: After other gods refuse the challenge, Ninurta emerges to conquer Anzu. (3) Donor/Consultation: Ninurta’s mother, Mami, counsels him before his departure. (4) Journey: Ninurta heads to Anzu’s mountain. (5) Battle: Ninurta and Anzu engage in their initial combat. (6) Defeat: The arrow Ninurta launches is ineffective. (7) Enemy ascendant: Anzu is seemingly insurmountable so long as he possesses the Tablet. (8) Hero recovers: Ninurta is taught by Ea how to defeat Anzu using the South Wind. Due to the fragmentary nature of the sources, however, we cannot speak definitively about narrative functions 9 through 12, though we assume that (9) the battle is rejoined, because (10) Anzu is ultimately defeated. The punishment of Anzu (11) and Ninurta’s triumph (12) cannot be identified with certainty.

The Storm God vs. the Serpent

A very compact version of the combat myth has survived from the Hurro-Hittite tradition. It relates the conflict between the Storm God and the Serpent, also known as Illuyankas. The text goes back to at least the Old Hittite Period (c. 1750-1500 BCE), but our surviving copies date to sometime between 1500 and 1190 BCE.[27] The action begins:

When the Storm God and the serpent fought each other in Kiskilussa, the serpent defeated the Storm God.

Then the Storm God invoked all the gods: “Come together to me.” So Inara prepared a feast.[28]

A grand banquet is then prepared, teeming with alcoholic drinks. The goddess Inara then enlists a man named Hupasiya to aid her in a scheme. She dresses in her finest clothes and lures the serpent from his lair, saying, “I’m preparing a feast. Come eat and drink!”[29] The serpent obliges her, comes up from his lair and drinks heartily at the banquet until he is incapacitated. This done, Hupasiya emerges and binds the serpent with a rope. The dragon thus ensnared, “The Storm God came and killed the serpent, and the gods were with him.”[30]

Though rather brief compared to the Ninurta myths, this ancient story still exhibits most of the core elements of the combat myth. Functions 1, 2, and 5 are quickly combined,[31] as the villain Illuyankas and the hero Storm God are introduced in the same breath relating the battle. Function 4 seems entirely lacking, however.[32] (5) The two battle, (6) with the initial defeat of the Storm God. (8)The Storm God recovers after (3) Inara aids him. (9) The second battle then occurs once Hupasiya has bound the Serpent. (10) This time the Storm God is victorious. (12) The hero’s triumph is recognized and celebrated by his fellow gods, who gather together with him at the battle’s conclusion.

With regard to imagery, the binding motif is notable, particularly for such a compact telling of the conflict. Its presence demonstrates that the binding topos was more than a superfluous narrative detail, recurrent in such combat myths simply for its prevalence in actual warfare tactics. Rather, it was an important formulaic motif—a persistent element in the combat myth genre.

Now, compared to those already considered, far more can be said about this myth regarding its agricultural significance and related cultic context. For the account we have of this Hittite combat myth is prefaced by a note explaining it as “the text of the Purulli (Festival).”[33] This Purulli Festival was the annual New Year’s festival that celebrated the regeneration of life and re-confirmed the kingship.[34] As we have noted, the defeat of the chaos-monster and the victory of the storm-god symbolized the destruction of disorder and infertility and the cyclical ascension of fertility and life. Thus the myth was recited at the annual festival, when the earth became fertile and green again:

…[T]hey speak thus—

“Let the land prosper (and) thrive, and let the land be protected” –and when it prospers and thrives, they perform the Purulli Festival.[35]

It was only at this special cultic event that the statue of the Storm God was brought out from its temple and wheeled on an ox-drawn carriage in a festive procession.[36] Trevor Bryce paints a vivid picture of this scene:

We can retrace the path of a festival procession as it leaves the palace gate and proceeds along the ceremonial way, exiting the city through the so-called King’s Gate, and passing outside the walls before again entering the city through the Lion Gate. We can imagine the processional way lined with the city’s inhabitants and foreign visitors, awaiting the spectacle soon to pass by them. In the distance, the songs of musicians, the pounds of the drums, cymbals, tambourines, and castanets can be heard, growing ever louder as the procession approaches. …Various cultic calls are made by designated performers and attendants—’aha!’, ‘kasmessa!’, ‘missa!’.[37]

Hittite processions led to a ḫuwasi stone outside the city: an altar-propped stele housed in a sacred shrine which represented the deity’s presence.[38] At the New Year, the Storm God traveled even farther, all the way to the city of Nerik, where the story of his defeat of the dragon Illuyankas was probably ritually re-enacted.[39] After this, the icon of the Storm God was returned to its usual residence within the city temple until the next great festal procession.

Marduk vs. Tiamet

The Enûma Eliš is the best-documented combat myth to survive from the ancient Near East. Composed in the latter part of the second millennium BCE,[40] it recounts the battle between the storm-god Marduk and the serpentine goddess Tiamet,[41] whose name means “Sea.” The narrative begins with an account of the creation of the gods by Tiamet and Apsu (Sea and Sky). Soon after their creation, however, this younger generation of gods grows too noisy and disruptive for their parents. Tiamet and Apsu therefore plan to destroy their boisterous offspring. However, the god Ea, hearing of the plot, intervenes and preemptively slays Apsu. This only temporarily neutralizes the threat, however, since Tiamet continues with her plan to destroy the other gods—now as an act of vengeance for the murder of her consort. To aid her in this fight, she forms and dispatches great helper beasts including “monster serpents,” “the Viper” and “the Dragon.”[42]

Ea hears of this new plotting too, and brings the news to the Divine Council. At first, the gods who might dare challenge Tiamet are either unable or too afraid to do so. Eventually, however, the young storm-god Marduk steps up to battle Tiamet. Marduk requests that in return for this service he be declared the ultimate king over the cosmos. To this the gods readily oblige:

Joyfully they did homage: “Marduk is king!”

They conferred on him scepter, throne, and vestment.[43]

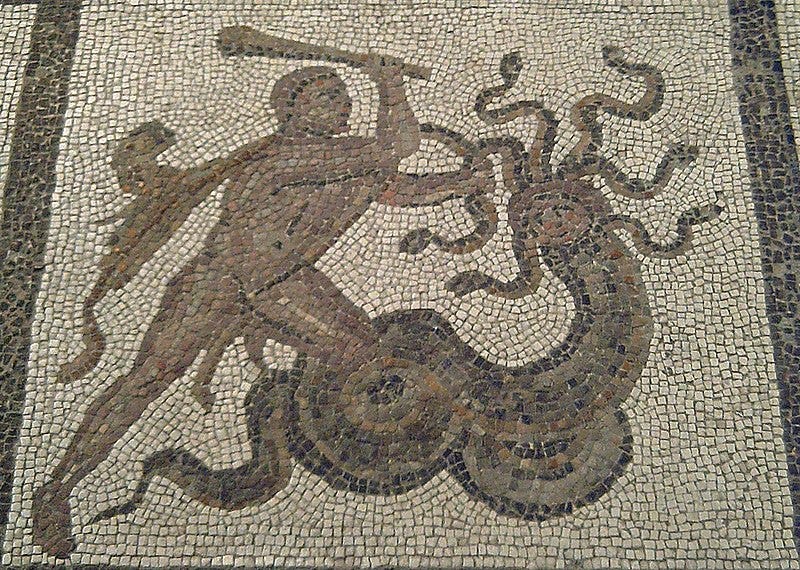

Marduk then mounts his storm-chariot, harnesses the winds, and readies lightning-bolt arrows as his weapons. Finally, sea-god and storm-god engage in single combat:

The lord spread out his net to enfold her,

The Evil Wind, which followed behind, he let loose in her face.

When Tiamet opened her mouth to consume him,

He drove in the Evil Wind that she close not her lips.

As the fierce winds charged her belly,

Her body was distended and her mouth was wide open.

He released the arrow, it tore her belly,

It cut through her insides, splitting her heart.

Having thus subdued her, he extinguished her life.

He cast down her carcass to stand upon it.[44]

So is the cosmic Sea defeated and her body trampled. Tiamet’s allies are terrified by the defeat and seek to escape, but Marduk rounds them up and binds them all:

The whole band of demons that marched on her right,

He cast into fetters, their hands he bound.

For all their resistance, he trampled (them) underfoot.

…valiant Marduk

Strengthened his hold on the vanquished gods,

And turned back to Tiamet whom he had bound.

The lord trod on the legs of Tiamet,

With his unsparing mace he crushed her skull.[45]

Marduk then picks up the corpse of Tiamet and, “like a fish” divides the body in two. Thus he fashions the heavens and the earth out of the defeated Sea, literally creating life and order out of the dead embodiment of sterility and Chaos. He then sets the proper boundaries for the raging waters and fashions humanity. The combat myth thus becomes a cosmogony. Marduk takes the Tablet of Destinies from the wrongful gods and fastens it on his own breast. The Norms have come to an orderly and just ruler. A palace/temple is constructed and the throne granted to him; his victory validates the gods’ proclamation of him as eternal king over the cosmos.

Again, the themes of kingship and order are fundamental to this combat myth. Only Marduk is able to slay Tiamet, making him uniquely qualified to rule as king. The rule of Tiamet was cruel and destructive, while the accession of Marduk inaugurates the prosperous reign of the beneficial storm-god.

Nearly all of the typical images reoccur: Marduk wields the weapons of the storm, binds Tiamet and her serpentine helpers, and tramples the carcasses of his enemies. Finally, the body of the chaos-monster is divided, becoming the fertile material for creation.

Plot-wise, the myth fits well into Forsyth’s schema. Briefly: (1) Lack/Villainy: Tiamet seeks to destroy the gods. (2) Hero emerges/prepares to act: Marduk emerges at the Divine Council. (3) Donor/Consultation: Marduk is promised kingship at the Council and prepares his weapons for battle. (4) Journey: Marduk sets out to confront Tiamet. (5) Battle: Marduk and Tiamet engage in single combat. (10) Victory: Marduk is triumphant. (11) The enemy punished: Marduk binds and tramples upon the conquered, then tears Tiamet in two. (12) Triumph: Marduk receives his kingship, a palace/temple is built for him, and all the gods chant his glorious names in the Divine Council. Interestingly, functions 6 through 9 (Defeat, Enemy ascendant, Hero recovers, Battle rejoined) are lacking here—an omission which may have served to heighten the philosophical/theological implications of the myth: Marduk is so powerful he needs but one attempt to defeat the forces of Chaos. Such zealous propaganda for the god, while emphasizing the power of the divine warrior, implicitly emboldens the religious participant: the greater Marduk is, the greater assurance one can have in the ultimate triumph of order over Chaos.

Like the Hittite combat myth’s connection with the New Year Purulli Festival, recitation of the Enûma Eliš was a key liturgical element in the Babylonian Akītu Festival: the twelve-day Babylonian New Year festival celebrating agricultural rejuvenation. Marduk’s victory over Tiamet was assured, and his reign meant the renewal of the world. While Chaos and death had for a time asserted themselves over the cosmos, the festival allowed for the turning back of the clock—indeed, all the way back to the creation of the world. To ritually enact this re-creation, on the fourth day of the festival the sesgallu priest would recite the Enûma Eliš to the temple statue of Marduk.[46] The following day, the priests would purify the temple of all spiritual pollution, thus ridding the sacred precincts of the contamination which had accumulated throughout the year. Recalling that the New Year meant a return to the completely pure state of the first Creation, this necessitated that all pollution be cleansed. So Julye Bidmead notes that the Akītu was a time of general ablution, when demons were expelled, diseases cured, and sins forgiven.[47] So too was the kingship renewed, as the king was ritually humiliated by the priest in the temple to show his ultimate subservience to Marduk.

On either the eighth or ninth day of the festival the great procession began. At this time, the statues of the gods were removed from their temples and processed through the streets of the city on jeweled chariots in great pomp and fanfare. Accompanied by singers, dancers, and musicians, the statue of Marduk traveled the processional way, the Babylonian via sacra, from the main gate of the Esagila (Marduk’s temple) out of the city’s Ishtar Gate to the bīt akīti (the “house of the Akītu”).[48] Like the ḫuwasi stone of the Hittite processions, the bīt akīti was a small cultic structure just outside the city. It served to house the gods during the festival, where they would remain for a few days before ultimately returning to their usual temples until the next New Year festival.

Baal vs. Sea (Yamm)

At last we come to the Ugaritic texts, the so-called Baal Cycle, consisting of Baal’s battles with Yamm (Sea), the seven-headed dragon Litan (sometimes written as Lotan), and Mot (Death). Though likely composed earlier than some of the myths already considered (c. 1400 BCE), I consider them here for more in-depth analysis, and as the most applicable segue into the Hebrew texts of the following chapter. For, since it is generally accepted that the West Semitic mythology preserved in these texts is exemplary of the broader Canaanite mythology which influenced the Hebrew Bible, these combat myths are our closest extant parallels to those of the early Israelites and thus provide crucial material for comparison.

The Baal-Yamm conflict is a rich example of the combat myth genre. Unfortunately, due to the fragmentary nature of the recovered materials, our knowledge of these myths is incomplete and our understanding of the Cycle’s narrative progression reliant on scholarly reconstructions. Nevertheless, we can still glean a more or less coherent series of events.

The first conflict begins, as we have it, in medias res: Yamm, the chaos-monster—who, like Tiamet, represents the raging Sea (and is himself some kind of dragon)—has sent messengers to the Divine Council, demanding that the storm-god Baal be taken captive and that Yamm’s kingship be acknowledged. As head of the Council, El consents to their demand and gives Baal over to Yamm as his prisoner. The rebel Yamm is thus made king.

However, the craftsman god Kothar-wa-Hasis constructs two clubs for Baal with which he might slay Yamm and reassert his own kingship. Baal takes the first and attacks Yamm, but the weapon proves ineffective. After this initial defeat, Kothar presents Baal with the second club, and with this Baal is finally able to slay Yamm:

The weapon leaps from Baal’s hand,

[Like] a raptor from his fingers.

It strikes the head of Prince [Yamm,]

Between the eyes of Judge River.

Yamm collapses and falls to the earth,

His joints shake,

And his form collapses.

Baal drags and dismembers (?) Yamm,

Destroys Judge River.[49]

For this victory over Yamm, Baal is thus proclaimed king:

So Yamm is dead!

[Baal reigns! (?),]

So he rules![50]

Now recognized as king, Baal demands of El that a palace/temple be built for him. Eventually El consents and allows one to be built on the storm-god’s holy mountain, Zaphon. He announces this to Anat, Baal’s consort, who then carries the news to Baal as a messenger and joyously proclaims El’s decree:

Adolescent Anat laughed,

She raised her voice and declared:

“Receive the good news, O Baal,

Good news I bring to you!

‘Let a house be given you like your brothers’,

A court, like your kin’s.

Call a caravan into your house,

Wares inside your palace.

Let the mountains bring you abundant silver,

The hills, the choicest gold.

And build the house of silver and gold,

The house of purest lapis lazuli.’”[51]

With his temple complete, Baal then travels (presumably in a triumphal procession) through the towns of the surrounding country, concluding finally with the victorious god’s entry into his temple. Once enthroned within, the storm-god sounds his mighty voice—his thunder that reverberates throughout the land:

Baa[l] gave forth his holy voice.

Baal repeated the is[ssue of (?)] his [li(?)]ps,

His ho[ly (?)] voice covered (?) the earth,

[At his] voice…the mountains trembled.

The ancient [mountains?] leapt [up?],

The high places of the ear[th] tottered.

The enemies of Baal took to the woods,

The haters of Hadd to the mountainsides.

And Mightiest Baal spoke:

“O Enemies of Hadd, why do you tremble?

Why tremble, you who wield a weapon against the Warrior?”

Baal looked forward;

His hand indeed shook,

The cedar was in his right hand.

So Baal was enthroned in/returned to his house.[52]

Thematically, concerns of fertility and kingship are clearly evident in this myth, while, with regard to specific images, the god’s mighty voice is clear from the above passage, and the dividing/dismembering of the defeated corpse may be attested at the battle’s close (though the condition of the text makes a definite translation impossible). In terms of plot, the narrative represents a fairly complete combat myth: (1) Lack/Villainy: Yamm dethrones the storm-god Baal. (2) Hero emerges/prepares to act: Baal moves to attack Yamm’s messenger, but is stopped by either Anat or Asherah.[53] The text becomes fragmentary, however, so that we do not know precisely about Baal’s next action(s). (3) Donor/Consultation: Kothar counsels Baal and gives him two clubs with which to defeat Yamm. Function 4 is not attested. (5) Battle: Using the first of Kothar’s clubs, Baal attacks Yamm. (6) Defeat: The first club proves ineffective against Yamm. (7) Enemy ascendant: Yamm stands strong after this first attack, Baal’s efforts having had little effect. (8) Hero recovers: Kothar gives Baal the second club. (9) Battle rejoined: Baal attacks Yamm with the second club. (10) Victory: The second attack proves successful, and Yamm collapses. (11) Enemy Punished: Uncertain, though according to Smith and Parker’s tentative translation, Baal dismembers Yamm. (12) Triumph: Baal goes through many towns, presumably on a triumphant procession, concluding ultimately with his enthronement in his palace/temple.

Many scholars believe that a cultic procession of the god’s idol is reflected in this final event.[54] Indeed, given the broad attestation of such practices throughout the ancient Near East, it seems likely that Ugarit too had its processional ceremonies, at which time the victorious storm-god—fresh from victory over the forces of Chaos—traveled amongst the people before being led back to his temple. Indeed, some have posited a Ugaritic New Year festival similar to the Purulli and Akītu festivals; though celebrated at the harvest-time rather than at spring, this festival would have shared similar characteristics as a celebration of fertility’s return.[55] While more cautious on the notion of an autumnal Ugaritic New Year festival, Mark Smith nevertheless acknowledges that “both the Baal-Yamm and Baal-Mot conflicts lead up to the autumn rains,”[56] and that

each major part of the cycle uses the imagery of the fall interchange period… This period witnesses the alternation of the eastern dry winds of the scirocco with the western rain-bringing winds coming off the Mediterranean Sea until the western winds finally overtake the eastern winds… The meteorological phenomenon of Baal’s coming in the storm over Yamm could be correlated with the coming of the fall rains. Scholars have long viewed Baal’s battle with Yamm as inspired by the eastward procession of the rain-storm from the Mediterranean Sea to the coast.[57]

Such a backdrop for the Baal Cycle certainly supports the idea that its combat myths had some role in a fall Near Year harvest festival. At this festival, the Baal Cycle would have likely served as a key cultic text, perhaps even as a sort of script for the religious pageant. So Arvid Kapelrud writes, “The arrival of the god to the temple, his enthronement and the hieros gamos are all acts that were not told for enjoyment; they represent cultic performances.”[58] Given what we know from other New Year festivals, such a conclusion is very compelling, and suggests that the enthronement of Baal was a chief ritual of the festival. While such enthronements may have played a part in other New Year festivals—since the storm-god’s accession to kingship is a ubiquitous theme in ancient Near Eastern combat myths and likely had a ritual counterpart (presumably connected to his re-installation within his temple/palace)—of the New Year festivals thus far considered, evidence for the ritual enthronement of the deity is strongest at Ugarit.[59] As we shall see, however, ancient Israel likely shared this practice.

Baal/Anat vs. the Dragon

In addition to Yamm, Baal is also said to have slain the seven-headed dragon Litan, which is either a helper of Yamm, or another designation for Yamm himself:[60]

When you killed Litan, the Fleeing Serpent,

Annihilated the Twisty Serpent,

The Potentate with the Seven Heads,

The heavens grew hot, they withered.[61]

A parallel tradition depicts Anat as the slayer of Yamm and his Dragon (Ugaritic “Tunnan”). She boasts:

Surely I fought Yamm, the Beloved of El,

Surely I finished off River, the Great God,

Surely I bound Tunnan and destroyed (?) him.

I fought the Twisty Serpent,

The Potentate with the Seven Heads.[62]

Elsewhere we read:

She sets a muzzle on Tunnan.

She binds him on the heights of Lebanon.

“Toward the desert (or: Dried up), shall you be scattered, O Yamm!

To the multitude of ḫt, O Nahar!

You shall not see (or: Indeed shall you see); lo! you shall foam up!”[63]

Here we reencounter the slaying of the sea dragon, which is said to have seven heads (cf. Ninurta’s enemy, the “Seven-headed Serpent”). In addition, we see again the binding motif encountered in other combat myths, such as Ninurta’s binding of the Stone Things, the binding of Illuyankas, and Marduk’s binding of Tiamet. Here the manner of binding is specified as muzzling. Finally, according to Wayne Pitard’s translation, Anat scatters him in the desert—by now a very familiar motif, as the chaos-monster’s body is divided/dismembered and then strewn.

Because these passages are only fragmentary allusions to a combat elsewhere unattested, they do not provide us with a narrative complete enough for a generic analysis based on plot. Beyond the obvious fact that they narrate a battle with a monstrous villain, only their scattered images—so recognizable now from the genre—allow us to suppose a more developed combat myth which once framed them.

Baal vs. Death (Mot)

Fresh from his victory over Yamm and the building of his temple, Baal is confronted by his ultimate enemy: Death (“Mot” in Ugaritic). Like Yamm, Mot is a representative of Chaos and destruction—indeed, as the very negation of life and fertility, he is the chaos-enemy par excellence. “The progression in the myth is logical,” notes E. Theodore Mullen. “To insure the fertility and stability of the cosmos, [Baal] must first make the universe secure from Yamm and the chaotic forces of the sea. Next he must overcome the forces of death and sterility, an equally important conflict.”[64] Indeed, I should say more important. With the threat of Mot, there is a progression in magnitude: the Dragon and Sea were formidable; Death is existential. Yamm was antagonistic; Mot is antithetical.

This final conflict begins after Baal, newly enthroned within his temple, sends messengers to Mot to communicate word of his kingship. But Mot responds by announcing his own insatiable appetite, and threatens to devour Baal. Indeed, Baal succumbs, and accepts submission to Mot, who then directs Baal to his underworld domain, commanding:

And you, take your clouds,

Your winds, your bolts, your rains;

…Lift the mountain on your hands,

The hill on top of your palms.

And descend to Hell, the House of “Freedom,”

Be counted among the inmates of Hell;

And you will know, O God, that you are dead.[65]

Lifting up the mountain, Baal is to descend into the pit and so enter Hell. His defeat is also depicted in more anthropomorphic terms by Mot, who elsewhere recounts:

Then I approached Mightiest Baal;

I took him like a lamb in my mouth,

Like a kid crushed in the chasm of my throat.

Dead is mightiest Baal,

Perished the Prince, Lord of the Earth.[66]

Baal, the god of rain and fertility, is thus killed by the chaos-enemy Death—eaten by the voracious consumer of life. Like Sea before him, Death now assumes his temporary dominance over the cosmos as the life-bringing rains cease. The gods can only mourn Baal’s end, lamenting a future ruled by bareness and sterility.

Eventually, however, Anat goes to retrieve Baal from Death. She finds Mot and attacks him. The two battle and Anat proves victorious. She divides/dismembers Mot, then scatters his body like seed, letting the birds eat his limbs. Mot overcome, Baal is thus restored to life, and upon his return is re-enthroned as king. Rain and fertility return to the world as a result of his resurrection, and El himself rejoices:

“I can sit and I can rest,

And my spirit within can rest.

For Mightiest Baal lives,

The Prince, Lord of the Earth, is alive.”[67]

After his resurrection, Baal seeks Mot, who—despite his confrontation with Anat—nevertheless remains undefeated. The two then engage in battle:

They eye each other like fighters,

Mot is fierce, Baal is fierce.

They gore each other like buffalo,

Mot is fierce, Baal is fierce.

They bite each other like serpents,

Mot is fierce, Baal is fierce.

They drag each other like runners,

Mot falls, Baal falls.[68]

The fight is evenly matched; both gods rage until mutual defeat or exhaustion. Eventually, though, El steps in to arbitrate and calls on Mot to withdraw. He does, and Baal is once again proclaimed king over the cosmos, having proved victorious over the great forces of Chaos: Sea, his associate Dragon, and Death.

Most of the themes of the combat myth are starkly illustrated here. The reflection of agricultural changes, for example, is clearly evident. As the parched, barren summer corresponds to Mot’s ascendency and the death of the storm-god, Mot’s defeat means agricultural rejuvenation. That his defeat by Anat is described as the sowing of new crops makes the association even more explicit. The return of fertility is celebrated as Baal’s resurrection, while the rather indecisive conclusion to his battle with Mot suggests the endless nature of the agricultural cycle. Mot is not annihilated; the battle is perennial.

Having already discussed the relationship of the Baal Cycle with Ugaritic religious cult, it is noteworthy that the conflict with Mot strengthens the hypothesis that a New Year festival existed at Ugarit and celebrated agricultural renewal through Baal’s victory over Sea and Death. At this time the statue of Baal was likely taken from its temple and brought through the surrounding towns before ultimately being processed back to the temple for a ritual re-enthronement of the deity.

Though more tenuous, we may even read philosophical and theological significance in the myth’s presentation of Death. Not surprisingly, Death is a malevolent force, its insatiable appetite serving as an apt metaphor for the ubiquity of the mortal condition and the transience of all life. Moreover, the fact that Death is never ultimately killed, and that Baal’s battle with him essentially ends in a draw, reflects a realistic reflection on the nature of mortality. Death is an intractable element of life; even mightiest Baal is subject to it.

Finally, all of these ideas (i.e., seasonal change, the ordering of the cosmos, mortality) are expressed as contests for kingship. Thus the myth intimately links natural order with political order, as different qualities and states of existence are presented as different kingdoms/kingships. The kingdoms of Yamm and Mot are destructive, bleak, and tyrannical. The kingdom of Baal, by contrast, is generally bountiful, joyous, and just.

The clearest generic motif attested in this combat myth is the dividing and scattering of Mot’s body. That Anat scatters the body like seed (to be eaten by birds) is reminiscent not only of her battle with the Dragon (whom she also scatters in uncultivated/desert places), but also of Ninurta strewing the defeated body of the dragon Azag like flour over the mountains. The similarities suggest a coherent topos: the defeated chaos-monster is divided, its body serving as nourishment in a once-barren place.

In Baal’s battle with Mot, we find again the fundamental plot progression of the combat myth: (1) Lack/Villainy: Mot contests the kingship of Baal. Functions 2 through 4 are absent,[69] and Baal appears to acquiesce immediately to the threat. (5) Battle: Mot devours Baal. (6) Defeat: Baal is killed. (7) Enemy ascendant: With Baal dead, the rains stop and the powers of death and sterility overshadow the world. (8) Hero recovers: Baal returns to life. (9) Battle rejoined: Baal and Mot engage in single combat. (10) Victory: While the actual result of the battle seems like more of a stalemate, El declares Baal the victor. (11) Enemy Punished: Baal does not appear to punish Mot, and in fact Mot is never actually killed. (12) Triumph: Baal re-ascends his throne, and Mot is now subject to his kingship. The forces of Chaos have been defeated.

To conclude, we have surveyed in this chapter some of the extant combat myths from the ancient Near East. These myths pit warrior storm-gods against the forces of Chaos, embodied variously as a dragon, the raging Sea, or even Death itself. The divine warrior rises to meet this challenge, and battles his enemy with the weapons of the storm. His first attempt ends in defeat, however, and in this temporary failure the forces of Chaos become dominant over the cosmos. Eventually, the warrior god revives and in his resurgence slays the enemy. Such victories often include the binding/muzzling, trampling, and dividing/scattering of the chaos-monster. With his victory, the storm-god sounds his mighty voice (thunder) and assumes kingship over the cosmos—an achievement celebrated at a New Year festival which included a triumphal procession of the god and perhaps a ritual enthronement of the deity within his temple.

In the next chapter, I shall show how these ancient Near Eastern combat myths—particularly those from Ugarit—provide insight into the combat myths the ancient Israelites. From there I shall demonstrate how and why later apocalyptic Jewish authors articulated their eschatological ideas in terms of the Hebrew combat myth.

NEXT: THE HEBREW COMBAT MYTH

[1] Other designations for the genre are sometimes used, such as “the myth of Chaoskampf” (struggle with Chaos) or the “conflict myth.” Less common designations also occur.

[2] Joseph Fontenrose, Python: A Study of Delphic Myth and Its Origins (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1959). Cf. Carolina López-Ruiz, When the Gods Were Born: Greek Cosmogonies and the Near East (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2010), 84-129.

[3] Fontenrose, Python, 194-209.

[4] Clifford, “The Roots of Apocalypticism,” 28.

[5] Mircea Eliade, The Sacred and the Profane: The Nature of Religion (New York: Harcourt, 1959), 77-8; emphasis original.

[6] Ibid., 79-80; emphasis original.

[7] Clifford, “The Roots of Apocalypticism,” 28.

[8] For an insightful analysis of this process see Fontenrose, Python, 5-9.

[9] Clifford, “The Roots of Apocalypticism,” 7.

[10] Fontenrose, Python, 262-4. He presents the following components as key elements: (1) The Dragon Pair, (2) Chaos and Disorder, (3) The Attack, (4) The Champion, (5) The Champion’s Death, (6) The Dragon’s Reign, (7) Recovery of the Champion, (8) Battle Renewed and Victory, (9) Restoration and Confirmation of Order. Adela Yarbro Collins made use of this schema in Adela Yarbro Collins, The Combat Myth in the Book of Revelation, Harvard Dissertations in Religion (Eugene: Wipf and Stock Publishers, 1976), 59-61.

[11] Forsyth, The Old Enemy, 441-4.

[12] Vladimir Propp, Morphology of the Folktale (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1928).

[13] Forsyth, The Old Enemy, 446. Those which may not always appear, and are therefore less essential, include functions 7-9.

[14] As does Clifford, “The Roots of Apocalypticism,” 28-31. It is important to note, however, that I am only making use of Forsyth’s schema and not attempting any kind of Proppian/functional analysis. Though Forsyth roots his schema in Proppian terminology, he does so with a critical eye to Propp’s weaknesses and methodological shortcomings (see Forsyth, The Old Enemy, 446, 447, 450). Moreover, his schema is comprehensive, synthesizing Propp, Fontenrose, as well as the Aarne and Thompson folktale index (ibid., 446). This schema will be helpful for the majority of ancient Near Eastern texts, though it becomes problematic in examinations of the Hebrew material (see Chapter 2).

[15] With the deliberate exception of the Ugaritic material, which is considered last and at greater length given its importance for the Hebrew combat myth.

[16] Thorkild Jacobsen, The Harps That Once...: Sumerian Poetry in Translation (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1987), 234. However, notes Forsyth, The Old Enemy, 55, the first known copies of this myth date only from c. 1800 BCE.

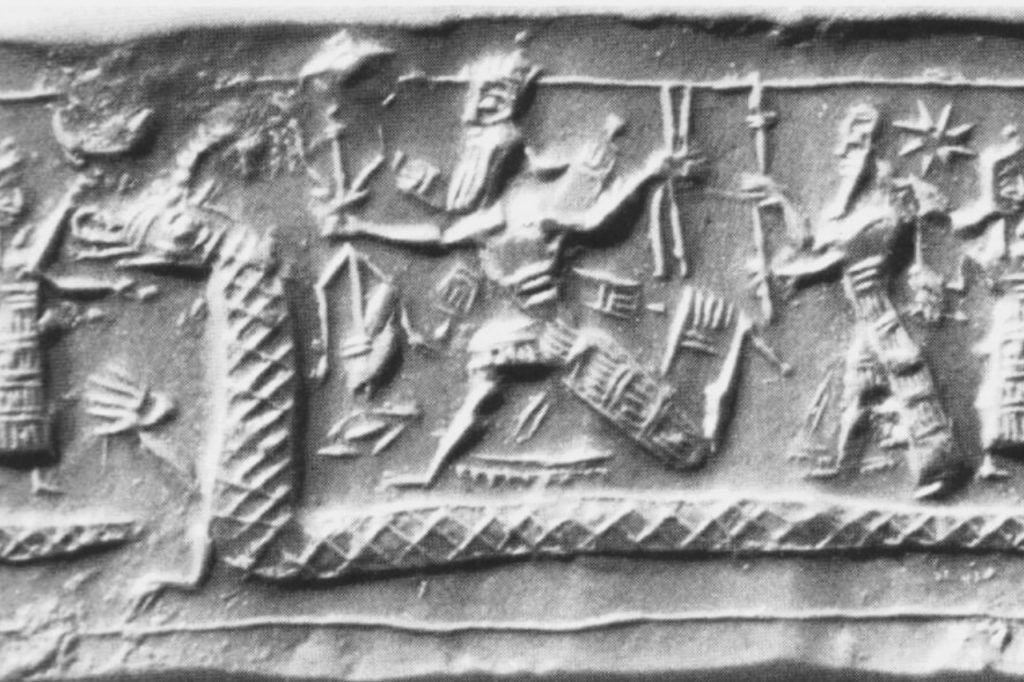

[17] Jacobsen, The Harps That Once, 237-8, lines 27, 28. The text is not clear about the nature of Azag. Jacobsen has suggested that it may be some kind of “tall hardwood tree,” but notes that there are “any number of possibilities” (234, 237 n. 8). Other commentators, such as William J. Hamblin, Warfare in the Ancient Near East to 1600 BC: Holy Warriors at the Dawn of History (London: Routledge, 2006), 124, refer to it simply as a dragon. Indeed, ninth-century BCE reliefs erected by Assyrian king Assurnasirpal II depict a god carrying thunderbolts and attacking a dragon-lion. These are thought to depict Ninurta attacking Azag, as is a similar scene found on Neo-Assyrian seals. See Jeremy A. Black and Anthony Green, Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia: An Illustrated Dictionary (London: British Museum Press, 1992), 36.

[18] Jacobsen, The Harps That Once, 239, lines 52-53, 55-56.

[19] Ibid., 243, lines 128-9, 133.

[20] The text is unclear. This interpretation accords with ibid., 235, line 4.

[21] Ibid., 245, lines 168-170, 173-5.

[22] Ibid., 249-250.

[23] This may also be seen as a double of Donor/Consultation.

[24] Hamblin, Warfare in the Ancient Near East, 125-6.

[25] ANET 112-13, Lines 5-9, 12-13.

[26] ANET 515, Tablet II, lines 28-35.

[27] Harry A. Hoffner and Gary M. Beckman, Hittite Myths, 2nd ed., Writings from the Ancient World (Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1998), 11.

[28] Ibid., 11, A i 9-11.

[29] Ibid., 12, B i 7-8.

[30] Ibid., 12, B i 17-18.

[31] (1) Lack/Villainy, (2) Hero emerges/prepares to act, and (5) Battle.

[32] (4) Journey.

[33] Hoffner and Beckman, Hittite Myths, 11, A i 1.

[34] Trevor Bryce, Life and Society in the Hittite World (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), 195.

[35] Hoffner and Beckman, Hittite Myths, 11 A i 4-8.

[36] Charles Allen Burney, Historical Dictionary of the Hittites (Lanham: Scarecrow Press, 2004), 86.

[37] Bryce, Life and Society, 189, 190.

[38] See Burney, Historical Dictionary of the Hittites, 87, 255-6.

[39] Bryce, Life and Society, 195.

[40] Benjamin R. Foster, Before the Muses: An Anthology of Akkadian Literature, 3rd ed. (Bethesda: CDL Press, 2005), 436. The precise date is much debated.

[41] While the Enûma Eliš does not explicitly describe Tiamet as a serpent or dragon, it does make reference to her “tail,” and a Neo-Assyrian cylinder seal (c. 900-750 BCE) showing a warrior with lightning in his hands treading upon the back of a long dragon may represent the slaying Tiamet (Clifford, “The Roots of Apocalypticism,” 17).

[42] ANET 62, Tablet I, lines 133 and 140.

[43] ANET 66, Tablet IV, lines 29-30; italics original.

[44] ANET 67, Tablet IV, lines 95-104.

[45] ANET, Lines 116-118, 127-30; italics original.

[46] Julye Bidmead, The Akītu Festival: Religious Continuity and Royal Legitimation in Mesopotamia, Gorgias Dissertations Near East Series (Piscataway: Gorgias Press, 2002), 60.

[47] Ibid., 72.

[48] Ibid., 96.

[49] CTA 2.iv.25-27 = Mark S. Smith and Simon B. Parker, Ugaritic Narrative Poetry, Writings from the Ancient World (Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1997), 104.

[50] CTA 2.iv.34-35 = ibid., 105.

[51] CTA 1.4.v.25-35 = Mark S. Smith, The Ugaritic Baal Cycle Vol. 1, Supplements to Vetus Testamentum, (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1994), 539.

[52] CAT 1.4.vii.29-42 = Mark S. Smith and Wayne Thomas Pitard, The Ugaritic Baal Cycle Vol. 2, Supplements to Vetus Testamentum (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 2009), 650.

[53] The text is corrupt here and the names of either goddess are possible restorations. See ANET, 130.

[54] See Oswald Loretz and Manfried Dietrich, Mythen und Epen IV (Gutersloh: Gutersloher Verlagshaus, 1997), 1168 n. 112; Johannes Cornelis de Moor, An Anthology of Religious Texts from Ugarit, vol. 16, Religious Texts Translation Series (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1987), 62 n. 277; Gregorio del Olmo Lete, Canaanite Religion: According to the Liturgical Texts of Ugarit (Bethesda: CDL Press, 1999) 139-41, 282-91; Dennis Pardee and Theodore J. Lewis, Ritual and Cult at Ugarit, Writings from the Ancient World (Leiden: Brill, 2002) 69-72. Smith, The Ugaritic Baal Cycle Vol. 1, more cautiously concludes, “This seems plausible, although it cannot be confirmed.”

[55] The best presentation of the thesis is Johannes Cornelis de Moor, New Year with Canaanites and Israelites, 2 vols., Kamper Cahiers (Kampen: Kok, 1972). He has interpreted some extant texts (describing celebratory dancing and music to lyres, tambourines, and cymbals) in light of this cultic rite (specifically U 5 V, no. 2: Obv.3-5).

[56] Smith, The Ugaritic Baal Cycle Vol. 1, 63.

[57] Ibid., 97-8.

[58] Arvid Schou Kapelrud, Baal in the Ras Shamra Texts (Copenhagen: G.E.C. Gad, 1952), 29-30.

[59] For the idea of the Ugaritic New Year festival as an “enthronement festival,” see ibid., 117, 123, 128, 143; Sigmund Mowinckel, The Psalms in Israel’s Worship (Oxford: Blackwell, 1962), 125, 132-4; L. R. Fisher and F. B. Knutson, “An Enthronement Ritual at Ugarit,” JNES 28 (1969): 156-7; Moor, New Year with Canaanites and Israelites, vol. 1, 4-10.

[60] For the former interpretation, see Kapelrud, Baal in the Ras Shamra Texts, 101-2. The latter interpretation is favored by Day, God’s Conflict, 14.

[61] KTU 1.5.i.1-4 = Smith and Parker, Ugaritic Narrative Poetry, 141.

[62] CAT 1.3.iii.38-42 = ibid., 111.

[63] KTU 1.83:9-13 = Wayne T. Pitard, “The Binding of Yamm: A New Edition of the Ugaritic Text KTU 1.83,” JNES 57, no. 4 (1998): 273.

[64] E. Theodore Mullen, The Divine Council in Canaanite and Early Hebrew Literature, Harvard Semitic Monographs (Chico: Scholars Press, 1980), 75-76.

[65] KTU 1.5.v.6-8, 14-17 = Smith and Parker, Ugaritic Narrative Poetry, 147.

[66] KTU 1.6.ii.21-23; 149, KTU 1.5.vi.9-10 = ibid., 156.

[67] KTU 1.6.iii.18-21 = ibid., 158.

[68] KTU 1.6.vi.16-22 = ibid., 162.

[69] (2) Hero emerges/prepares to act, (3) Donor/Consultation and (4) Journey. Function 2 would be redundant, since Baal has already emerged to defeat Yamm. Additionally, one could see Anat’s help in reviving Baal as fulfilling the role of function 3, the way Inara can be seen as the Donor in the Illuyankas combat myth.