God's Fight with the Dragon, Part III

Axial Age Transformations of the Combat Myth

Developments of the Hebrew Combat Myth

No doubt owing to its significance in cultic life, the Israelite combat myth became an extremely potent topos in Hebrew literature. It was one configuration that later prophets and writers could count as a given for their audience, be they commoners or kings. Moreover, the whole complex of almost archetypal meanings informing the myth provided an infinitely rich treasure-trove of images from which to draw. Power, hubris, victory, death, defeat, revival, celebration, triumph—all had their place in the combat myth; all could be employed to heighten the semantic and expressive levels of one’s message.

Of course, such images were not taken indiscriminately, outside the demands of context; essentially, it was the chief themes of the myth which provided the basis for association and metaphor. Thus, the full range of agricultural, cultic, political, and philosophical interconnections are brought to bear. Re-creation, renewal, feast, purification, epiphany, procession, victory, kingship, and the assertion of justice—all interwoven in the combat myth—likewise interweave in allusion. Some theme or image may be more prominent in one writer’s metaphor, some in another, but all are at least latent and implicit, none is far from the surface. Thus, reading of restoration one minute, we should not be surprised if the author then alludes to a procession or enthronement. Though a seeming non sequitur, familiarity with the combat myth and its cultic context makes the connection logical and even expected. This said, we can begin to examine some of the most important applications and revalorations of the combat myth in Israel’s history.

After the fundamental significance of the Chaoskampf myth in the cult, the most important by far is the one it took in times of national persecution or disaster. In particular, concerns over renewal/restoration and the assertion of lapsed justice help to explain its relevance in moments of defeat. In such crises, the myth was invoked as part of a divine call to action.[1] Thus, Yahweh’s past victories against the chaos-forces were consulted as the archetype for his salvific work, to which men in later times of trial could harken back. If Yahweh had defeated the enemy then, surely he could do it again.

To be sure, the most disastrous event in Israel’s history before the first century CE was the Babylonian Exile, when Nebuchadnezzar II invaded Judah, ended the monarchy, destroyed the Temple, and deported a great number of Jews to Babylon. In the wake of such tragedy, many struggled to make theological sense of what had happened. In their desperate prayers and lamentations, some in exile turned to the Chaoskampf tradition from old Israelite myth and cult as a reminder (and perhaps, in some sense, a reenactment) of Yahweh’s power to overcome great foes. Indeed, the cosmogonic aspect of the myth—that is, the Creation of Israel’s world, whose fundaments had been the Temple and Davidic Monarchy—became particularly salient for a people still smarting from the recent destruction of those national pillars. Recollections of Yahweh’s great victory thus became an impassioned plea for him to repeat that epic battle—to become the divine warrior yet again and rescue his people from the destructive grips of a great enemy. As before, this victory would bring about the creation of a new Israel, a new king and a new Temple. As ever, the combat myth became the framework for interpreting political realities: Babylon was the beast, Yahweh the vanquishing storm-god.

We find an example of such use in Psalm 74, where the author examines his people’s suffering despite Yahweh’s supposed power and Israel’s former glory. He pleads with Yahweh to vindicate his humiliated people, and thus his own name, by coming again as the divine warrior:

How long, O God, is the foe to scoff?

Is the enemy to revile your name forever?

Why do you hold back your hand;

why do you keep your hand in your bosom?

Yet God my King is from of old,

working salvation in the earth.

You divided Sea by your might;

you broke the heads of the Dragons in the waters.

You crushed the heads of Leviathan;

you gave him as food for the people in the wilderness. (vv. 74:11-14)

Likewise Psalm 77:

Will the Lord spurn forever,

and never again be favorable?

Has his steadfast love ceased forever?

Are his promises at an end for all time?

…I will call to mind the deeds of Yahweh;

I will remember your wonders of old.

I will meditate on all your work,

and muse on your mighty deeds.

…When the Waters saw you, O God,

when the Waters saw you, they were afraid;

the very Deep trembled.

The clouds poured out water;

the skies thundered;

your arrows flashed on every side.

The crash of your thunder was in the whirlwind;

your lightning lit up the world;

the earth trembled and shook.

Your way was through the Sea,

your path, through the mighty Waters;

yet your footprints were unseen. (vv. 7-8, 11-12, 16-19)

Of all the writers to employ the combat myth in this way, one in particular demands special attention. He is the author of Isaiah 40-55 (called Second or Deutero-Isaiah), and he employs Chaoskampf traditions extensively to this end. Indeed, fundamental to his entire prophetic message is the metaphorical comparison of Israel’s impending restoration from exile with the rejuvenation which followed Yahweh’s victory over the forces of Chaos. So we read:

Awake, awake, put on strength,

O arm of Yahweh!

Awake, as in days of old,

the generations of long ago!

Was it not you who cut Rahab in pieces,

who pierced the Dragon?

Was it not you who dried up Sea,

the Waters of the Great Deep;

who made the depths of Sea a road

for the redeemed to cross over?

So the ransomed of Yahweh shall return,

and come to Zion with singing;

Everlasting joy shall be upon their heads;

they shall obtain joy and gladness,

and sorrow and sighing shall flee away.

I, I am he who comforts you;

why then are you afraid of a mere mortal who must die,

a human being who fades like grass?

You have forgotten Yahweh, your Maker,

who stretched out the heavens

and laid the foundations of the earth.

You fear continually all day long

because of the fury of the oppressor,

who is bent on destruction.

But where is the fury of the oppressor?

The oppressed shall speedily be released;

they shall not die and go down to the Pit,

nor shall they lack bread.

For I am Yahweh your God,

who troubles the Sea so that its waves roar—

Yahweh of Hosts is his name.

I have put my words in your mouth,

and hidden you in the shadow of my hand,

stretching out the heavens

and laying the foundations of the earth,

and saying to Zion, “You are my people.” (Is 51:9-16)

The prophet begins by pleading with his god, literally attempting to rouse him as though he had fallen asleep and thus become inattentive to the calamities befalling Israel. He harkens back to the “days of old,” when Yahweh was still a warrior fighting for his people. He demonstrated his power then by defeating the Dragon Rahab and the roaring Sea, whom he divided so that Israel might cross into the Promised Land. With this connection, Deutero-Isaiah highlights the fact that the Exodus tradition is itself based on the combat myth. However, in an imaginative and bold move, he adds to the traditional topos (present even in Exodus 15) which linked Yahweh’s dividing/dismembering of the Sea and Israel’s crossing of the Red Sea. Indeed, he relates this salvific passage to the Sacred Way of the New Year festival. Thus, in a crucial metaphorical linkage, Deutero-Isaiah makes the Exodus crossing the via sacra of the New Year procession. With this brilliant relationship, the dividing and trampling motifs are combined: the Sea itself is the Way trampled by the faithful en route to the Temple.

Deutero-Isaiah continues the metaphor: after Yahweh defeated Sea, he established Creation (“stretching out the heavens…”); now he is urged to fight again, not Sea but Babylon. He is compelled to create again, not the first Monarchy and Temple—which lie in ruins—but new ones. Then his chosen people shall return to Zion a saved and redeemed nation, not sent to Death’s Pit as through the famine of barren summer. Rather, in abundance, they shall march to Zion “with singing” as they had during the New Year procession. For sorrow and sighing will flee away just as the chaos-waters were said to flee at God’s rebuke.

As this passage demonstrates, the language used to articulate the future hope of Yahweh’s intervention and restoration could be drawn not only from the combat myth generally, but the New Year festival specifically as the cultic enshrinement of that myth. Writing during the Babylonian Exile, Deutero-Isaiah draws frequently from the festival as a powerful metaphor for Israel’s eventual renewal. Mowinckel summarizes this succinctly, writing:

Interpreters have always been aware of the close relationship between the enthronement psalms and Deutero-Isaiah…[who is] dependent on the ideology and style of the enthronement psalms. That is to say, he has consciously imitated and used them as a pregnant expression of the message he is bringing.[2]

So the festival’s processional road features prominently. Such, we recall, was the mĕsillâ, the paved road, which indeed permeates the book of Isaiah as a kind of leitmotif. Here it is reimagined as the road which will run from Babylon to Zion, carrying the exiles home:

Then the eyes of the blind shall be opened,

and the ears of the deaf unstopped;

then the lame shall leap like a deer,

and the tongue of the speechless sing for joy.

For waters shall break forth in the wilderness,

and streams in the desert;

the burning sand shall become a pool,

and the thirsty ground springs of water;

the haunt of jackals shall become a swamp,

the grass shall become reeds and rushes.

A processional road (mĕsillâ) shall be there,

and it shall be called the Sacred Way;

the unclean shall not travel on it,

but it shall be for God’s people;

no traveler, not even fools, shall go astray.

No lion shall be there,

nor shall any ravenous Beast come up on it;

they shall not be found there,

but the redeemed shall walk there.

And the ransomed of Yahweh shall return,

and come to Zion with singing;

everlasting joy shall be upon their heads;

they shall obtain joy and gladness,

and sorrow and sighing shall flee away. (Is 35:5-10)

The return of the captives is here pictured as Yahweh’s cosmic rejuvenation (the divine warrior’s “Shalom” in Hanson’s terms), and the path of the exiles as the Sacred Way, the processional road of the New Year festival. Only the redeemed shall walk there, as only the righteous/purified could enter the Gate of Righteousness,[3] and no Beast will any longer be a threat. The exiles shall return to Zion with singing and celebration along this “eschatological via sacra,”[4] and here again, “sorrow and sighing” flee away like the rebuked chaos-waters.

Indeed, even the language of physical healing recalls the festival. As Eliade observed, the New Year was indeed a re-creation, a return to the pure time of origin. All accumulations of stain or imperfection were abolished. All Nature returned to a state of original purity. For this reason, the New Year was not only a time of ritual ablution, but also associated with healing. Eliade writes that

since ritual recitation of the cosmogonic myth implies reactualization of that primordial event, it follows that he for whom it is recited is magically projected in illo tempore, into the “beginning of the World”; he comes contemporary with the cosmogony. What is involved is, in short, a return to the original time, the therapeutic purpose of which is to begin life again, a symbolic rebirth.[5]

The “eschatological via sacra” described in Isaiah 35 reappears in Isaiah 40, which likewise leads the exiles back to Zion through the desert:

A voice cries out:

“In the wilderness, clear the Road of Yahweh!

Make straight in the desert a processional way (mĕsillâ) for our God!

Every valley shall be lifted up,

and every mountain and hill be made low;

the uneven ground shall become level,

and the rough places a plain.

Then the glory (kbôd) of Yahweh shall be revealed,

and all people shall see it together,

for the mouth of Yahweh has spoken.”

…Ascend (‘ālâ) a high mountain,

O herald of good tidings to Zion;

lift up your voice with strength,

O herald of good tidings to Jerusalem,

lift it up, do not fear;

say to the cities of Judah,

“Behold your God!”

See! Lord God comes with might,

and his arm rules for him. (Is 40:3-5, 9-10a)

This passage is brimming with imagery from the procession of the New Year festival. Of special interest, however, is the processional herald, crying out to the people, “Clear the Road of Yahweh!” This figure is not simply a poetic construction. Evidence shows that actual heralds were responsible for leading ancient cultic processions. So, for example, in the eleventh book of The Golden Ass, Apuleius notes in his description of the Isis procession: “And there were many whose job it was to cry out, ‘make the road clear for the sacred objects’.”[6] Compare also the description of the Akītu procession and its emphasis on clearing the processional road for the passing deity:

From Hostile Elam [Nabu] entered upon a road of jubilation, a path of rejoicing … of success to Su-an-na. The people of the land saw his towering figure, the ruler in (his) splendor. Hasten to go out (Nabu), Son of Bel, you who know the ways and the customs. Make his way good, renew his road, make his path straight, hew him out a trail.[7]

Such heralds would certainly have been part of the New Year procession in ancient Israel when, as the people excitedly clamored to glimpse the deity—when his glory (the kbôd of his ark) was revealed in cultic epiphany (explaining the prophet’s reiterations of “Behold your God!” and “See!”)—a clear path was needed for passage. Such would have been the role of the processional herald.

However, the herald’s proclamations were more than simple calls for room. Indeed, in Deutero-Isaiah’s scene, after “ascending” (ālâ) the processional road (mĕsillâ) up the Temple mount, the herald was also to proclaim the “good news.” These are not mere general exultations, however, as the Hebrew verb bśr usually means “to report good news” in a very specific sense—namely “to report the good news from the battlefield.” Indeed, this association with military triumph renders it an almost technical term: the bśwrh is the good news proclaimed by a messenger/herald after victory in battle (so e.g., 2 Samuel 18:20-27; 2 Kings 7:9;). So we find that bśr is the verb used to announce the death of enemy kings (e.g., 1 Samuel 31:9; 2 Samuel 1:20; 4:10; 18:19-32). Used in the context of the New Year festival—the cultic celebration of the storm-god’s defeat of the chaos-monsters—the term thus refers specifically to Yahweh’s victory in battle against the forces of Chaos. The enemy king (Yamm or Mot) is dead; Yahweh, instead, has become king.

Such, indeed, was the significance of bśr and its cognates even in the Baal Cycle. There we read how, after Baal slew Yamm, Anat comes as a herald from El to Baal with message that, since he is now king, a palace/temple can be built for him:

Adolescent Anat laughed,

She raised her voice and declared:

“Receive the good news (bśr), O Baal,

Good news (bśwrh) I bring to you!

‘Let a house be given you like your brothers’,

A court, like your kin’s.[8]

Sigmund Mowinckel observes that “[t]he term ‘glad tidings’ (bšrt) was already used in Ugarit about the announcement that Baal had again become alive, and in the same terms the cultic festival announced to Israel the appearance of Yahweh as king and his enthronement.”[9] Such appears to be the significance of “reporting the good news” (the Hebrew verb bśr) in the New Year Enthronement Psalms:

Sing to Yahweh, bless his name;

report the good news (baśśĕrû) of his salvation from day to day.

…Say among the nations, “Yahweh has become king!” (Ps 96:2, 10a)

Such was the task of the New Year festival herald, about whom we may briefly conjecture further, since a survey of the usages of bšr in the Hebrew Bible reveal an intimate connection with a specific figure: the son(s) of the high priest of the ark. So, for example, Ahimaaz, son of Zadok, high priest of the ark, bears the “good news” to David that the would-be usurper Absalom is dead (2 Samuel 18). Likewise, in 1 Kings 1:42, Jonathan, son of the other high priest of the ark, Abiathar, relates the “good news” to the would-be usurper Adonijah that Solomon has become king. Notably, in 1 Sam 4:17, an unnamed Benjaminite must report the good news from the battlefield (of the ark’s capture), since Hophni and Phineas, the sons of the high priest of the ark, Eli, have themselves been killed in the battle. These, and other passages, suggest that the traditional herald/messenger of the good news was the son of the high priest of the ark—a fitting designation, given the ark’s importance in the New Year festival. The would-be usurper king, Sea or Death, was defeated, and the son of the high priest could march triumphantly at the fore of the procession, proclaiming the good news and demanding, “Clear the Road of Yahweh!”

It is from just this festal scene that Deutero-Isaiah draws the basis for his cosmic vision in the earlier passage above and again a few verses later:

How beautiful upon the mountains

are the feet of the herald of the good news (mĕbaśśēr),

who announces peace,

the herald who brings good news (mĕbaśśēr ṭôb),

who announces salvation,

who says to Zion, “Your God has become king!”

Listen! Your sentinels lift up their voices;

together they sing for joy;

For in plain sight they see

the return of Yahweh to Zion. (Is52:7-8)[10]

The “good news,” originally the proclamation of Yahweh’s ultimate victory over the chaos-forces by the herald, is here imagined as Yahweh’s victory over the nations which brings his people home. “Yahweh has become king!”—the exclamation of the festival—is now used to symbolize Yahweh’s re-assumption of power once Israel is restored. Peace is at hand now that Yahweh’s war with the Dragon (Babylon) is over. Now the people can sing just as they sang at his procession, since now they see Yahweh return to Zion, just as he used to process up his hill and into his Temple for enthronement. Such is the role of the combat myth and the New Year festival in Deutero-Isaiah.

Though, while Deutero-Isaiah was the most important prophet to employ the combat myth and its cultic festival in this way, he was certainly not the first. Even before the Exile, Nahum’s prophetic message spoke to the late seventh century downfall of Assyria in terms of the primordial battle:

A jealous and avenging God is Yahweh,

Yahweh is avenging and wrathful;

Yahweh takes vengeance on his adversaries

and rages against his enemies.

…His way is in whirlwind and storm,

and the clouds are the dust of his feet.

He rebukes the Sea and makes it dry,

and he dries up all the Rivers;

…Yahweh is good,

a stronghold in a day of trouble;

he protects those who take refuge in him,

even in a rushing Flood.

He will make a full end of his adversaries,

and will pursue his enemies into darkness.

Why do you plot against Yahweh?

He will make an end;

no adversary will rise up twice.

…Look! On the mountains: the feet of one

who brings good news!

Who proclaims peace!

Celebrate your festivals, O Judah,

fulfill your vows,

for never again shall the wicked invade you;

they are utterly cut off. (Nah 1:2, 3b-4a, 7-9, 15)

Nahum is certainly similar to the later prophet in his metaphorical utilization of the combat myth and the New Year festival. Yahweh is again the cloud-rider storm-god, whose mighty rebuke subdues the traditional enemies of the Chaoskampf: Sea and River. In an interesting boast, the prophet even alludes to the traditional progression of the combat myth in which the storm-god’s first attack would prove ineffectual, thus allowing the adversary to “rise up twice.” Like Marduk, however—whose immense power demanded only one attempt to slay the Sea—Yahweh can likewise boast that the first battle with his enemies shall prove the last. Finally, and in very similar language to Deutero-Isaiah, the herald of the festival is mentioned. The herald tops the Temple mount and declares the good news of Yahweh’s ultimate victory (here, over Assyria), allowing Judah to celebrate the Festival of Booths without fear of invasion. As Isaiah shows, of course, this assurance proved misplaced, since the very power that destroyed Assyria then came and subjugated Judah. Yahweh’s enemies did indeed rise twice, or, rather, the Yamm of Assyria fell, only to be followed by the swallowing Mot of Babylon. So could the message of Nahum become the message of Deutero-Isaiah—only now writ larger, cosmicized into Axial Age religious proportions.

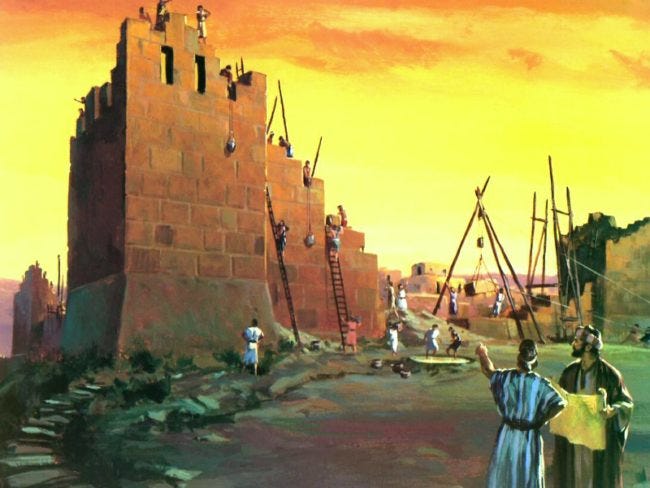

Eventually, however, Isaiah’s long hoped-for Restoration did occur. With the Persian defeat of Babylon, the Jewish exiles were indeed allowed to return to their homeland and begin rebuilding the national pillars which war had destroyed decades earlier. In a basic sense, then, the expectant visions of Isaiah were fulfilled. Babylon, the chaos-monster, was destroyed and Israel had traveled the desert Way back to a new Temple. With this apparently successful conclusion, one might expect a cessation of grand visions for return and the renewal of Israel. However, various historical developments following the Restoration led to precisely the opposite: rather than ceasing, prophetic visions of rejuvenation and re-creation actually intensified.

In part, this was justified by the very real disappointments and frustrations of reconstruction. On the other hand, and not without irony, the continuance of yearning for cosmic renewal was a product of its own indulgence: it was a dissatisfaction with reality engendered by an over-exuberant hope. Given the lofty, cosmic language used so poetically and with such power by Isaiah and other visionaries, no restoration could ever have matched the rhetoric. With every frustration, delay, false-start, and failure to return Israel to its imagined former glory, disappointment grew, and the prophetic visions of a Second Paradise now but served as a foil to the lackluster realities on the ground. Surely this was not the promised rejuvenation, some must have thought. Surely it is still to come.

With these developments, it is not surprising that the hoped-for event comes to lose its moorings in historical reality. Since presumably unfulfilled, the idea of restoration continued to be developed and, with time, took on a truly cosmic scope. So, as Mowinckel puts it, “The salvation to come is looked upon as an enthronement day of Yahweh with cosmic dimensions—such in short is the substance of the prophecy of re-establishment and later also of eschatology.”[11] This is why the combat myth and apocalypticism are so intricately linked. The language of the New Year poetically employed by prophecy becomes infinitely enlarged. In this way, the temporary dominance of the Chaos at the end of the year is transformed into world cataclysms at the End of Time. The storm-god’s defeat of these forces and the return of original fertility is transformed into Yahweh’s final battle with the forces of Evil and the ultimate restoration of the earth back to the Edenic Paradise of the Beginning. The apocalypse is essentially the cosmic New Year.

Such cosmic aggrandizement of the New Year likely provides the background for the so-called Isaianic Apocalypse (chapters 24-7), written probably a century or more after Israel’s return from captivity and later embedded into earlier prophecies. It reads in part:

Your dead shall live, their corpses shall rise.

O dwellers in the dust, awake and sing for joy!

For your dew is radiant dew,

and the earth will give birth to those long dead.

Come, my people, enter your chambers,

and shut your doors behind you;

hide yourselves for a little while

until the wrath is past.

For Yahweh comes out from his Place

to punish the inhabitants of the earth for their iniquity;

the earth will disclose the blood shed on it,

and will no longer cover its slain.

On that Day, Yahweh with his cruel and great and strong sword will punish Leviathan, the fleeing serpent, Leviathan the twisting serpent, and he will kill the Dragon that is in the Sea. (Is 26:19-27:1)

“The Day of the Lord,” the epiphany day of Yahweh at his harvest New Year festival, becomes the day of impending restoration of the entire cosmos, and the judgment for Israel’s enemies.[12] So the combat myth, notably the themes of rejuvenation and the assertion of justice, undergirds apocalyptic expectation. Of particular note in this passage, however, is the antiquity of the mythic traditions employed despite the relatively late date of the text.[13] The language describing Leviathan here in Isaiah 27:1 is so similar to that describing Baal’s defeat of Litan that scholars propose direct dependence on a common West Semitic tradition:[14]

Isaiah 27:1

…punish Leviathan the fleeing serpent,

Leviathan the twisting serpent…

KTU 1.5.i.1-4

…killed Litan, the Fleeing Serpent,

Annihilated the Twisty Serpent…

This late use of particularly ancient mythic traditions becomes a recurrent tendency in apocalyptic literature (and one I shall further explore in the following chapter).

While the resurrection imagery in this passage could simply be metaphorical for Israel’s expected renewal as a nation, it may represent the apocalyptic expectation of bodily resurrection in the radical new world order after Yahweh’s epiphany and judgment—a utopian world where there shall be no more death for Israel’s faithful. In this sense, we see the apocalyptic reflex of the storm-god’s defeat of Death. The prophet writes similarly in a passage a few verses earlier:

And he will destroy on this mountain

the shroud that is cast over all peoples,

the sheet that is spread over all nations;

he will swallow up Death forever.

Then the Lord God will wipe away the tears from all faces,

And the disgrace of his people he will take away from all the earth,

For Yahweh has spoken.

It will be said on that day,

Lo, this is our God; we have waited for him, so that he might save us.

This is Yahweh for whom we have waited;

let us be glad and rejoice in his salvation. (Is 25:7-9)

As noted before, we find here an ironic reversal of the Baal/Mot (or rather Yahweh/Mot) combat myth. Whereas Death conquered Baal by swallowing him, here Yahweh swallows Death. Thus Yahweh is the divine warrior who defeats the forces of death and destruction—not just at the end of the year, but forever. The victory has a decidedly eschatological tone, as his success over those forces inaugurates a radically new era of divine intimacy, joy, forgiveness, and deliverance from oppression. Day notes that these sections of Isaiah are best understood as “proto-apocalyptic or late prophecy,” and posits, quoting G. W. Anderson, that they belong “to that phase in prophecy in which the sharp contours of the here and now begin to be lost in more spacious visions of a transformation of all things.”[15]

Nowhere is this tendency more pronounced than in chapters 9-14 of Zechariah, usually attributed to an author called Second Zechariah. Though these post-Exilic texts are notoriously difficult to date,[16] they are clearly at home in the “proto-apocalyptic” tradition, if not representative of full-blown apocalypticism. So we read:

See, the Day of Yahweh is coming, when the plunder taken from you will be divided in your midst. For I will gather all the nations against Jerusalem to battle, and the city shall be taken and the houses looted and the women raped; half the city shall go into exile, but the rest of the people shall not be cut off from the city. (Zech 14:1-2)

So the world descends into utter Chaos. The deprivations and decay of the closing year are eschatologized into the ultimate ruin of the city of Jerusalem. However, this moment of Chaos’ triumph does not last long. As in the combat myth, this is the cue for the glorious divine warrior. So we read in the next verse:

Then Yahweh will go forth and fight against those nations as when he fights on a day of battle. On that Day his feet shall stand on the Mount of Olives, which lies before Jerusalem on the east; and the Mount of Olives shall be split in two from east to west by a very wide valley; so that one half of the Mount shall withdraw northward, and the other half southward. And you shall flee by the valley of the mountain, for the valley between the mountains shall reach to Azal; and you shall flee as you fled from the earthquake in the days of King Uzziah of Judah. (14:3-5b)

The battle won, so follows the rejuvenation and assumption of kingship:

Then Yahweh my God will come, and all the Holy Ones with him. On that Day there shall not be either cold or frost. And there shall be continuous day (it is known to Yahweh), not day and not night, for at evening time there shall be light. On that Day living waters shall flow out from Jerusalem, half of them to the eastern sea and half of them to the western sea; it shall continue in summer as in winter. And Yahweh will become King over all the earth; on that Day Yahweh shall be one, and his name one. (14:5c-9)

Finally, as if to make all of these connections with the New Year festival and the combat myth explicit, the prophet concludes:

Then all who survive of the nations that have come against Jerusalem shall go up (‘ālâ) year after year to worship the King, Yahweh of Hosts, and to keep the Feast of Tabernacles. …And there shall no longer be traders in the House of Yahweh of Hosts on that Day. (14:16, 21b)

The language of the prophet is certainly far beyond “the here and now,” describing rather scenes of truly cosmic restoration and transformation. His use of the combat myth—and, more specifically, the New Year Feast of Tabernacles—is notable. Again, the festival’s “Day of the Lord” is projected as a cosmic event: Yahweh is revealed, not in the epiphany of his ark during the procession, but in person as it were—as the wrathful divine warrior himself appearing to the entire world. So Yahweh will fight, bestriding like a colossus the divided Mount of Olives. Entering Jerusalem from the east—echoing the ark’s festal procession through the Temple’s eastern gate—he then defeats Israel’s enemies, whose typical association with the chaos-monsters is assumed. His (re)assumption of kingship is the consequence of this victory, and Yahweh is proclaimed king over the cosmos. Finally, the Temple is cleansed of impurity (the “traders” being expelled) in a ritual re-purification expected of the New Year, and all the nations of earth go up year after year to celebrate the Feast of Tabernacles.

From here it is not too difficult to see the contours of later, full-blown apocalypticism, as well as the role which the combat myth and the New Year festival will play within that emerging tradition. Such developments are the focus of the next chapter and are crucial for understanding the role and importance of the combat myth in the Gospel of Mark.

NEXT: APOCALYPTICISM AND THE COMBAT MYTH

[1] See Jon Levenson, Creation and the Persistence of Evil: The Jewish Drama of Divine Omnipotence (San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1988), 17-26.

[2] Mowinckel, The Psalms in Israel’s Worship, 116-17.

[3] Cf. Pss 24, 118.

[4] Mowinckel, The Psalms in Israel’s Worship, 171.

[5] Eliade, The Sacred and the Profane: The Nature of Religion, 82.

[6] Met. 273.13-14, as noted in ABD, “Processions,” 472.

[7] Paul Volz, Jesaia II, Kommentar Zum Alten Testament (Leipzig: Deichertsche, 1932), 4.

[8] CTA 1.4.v.25-9 = Smith and Pitard, The Ugaritic Baal Cycle Vol. 2, 539.

[9] Mowinckel, The Psalms in Israel’s Worship, 142.

[10] For the translation “Yahweh has become king,” see ibid., 107-9.

[11] Ibid., 189; emphasis mine.

[12] For the original motif of “judgment” and Yahweh’s epiphanic festival, see ibid., 146-50.

[13] Many scholars have proposed a late date for the Isaiah Apocalypse. In his commentary on Isaiah 1-39, Joseph Blekinsopp notes, “Study of the language, vocabulary, themes, and tone of these chapters persuaded practically all critical readers as early as the first half of the nineteenth century…that they come to us from the time of the Second Temple,” Joseph Blenkinsopp, Isaiah 1-39: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary, The Anchor Bible (New York: Doubleday, 2000), 347-8. However, others have proposed an earlier composition in the sixth century BCE, including Cross, Canaanite Myth and Hebrew Epic, 135, and Blenkinsopp himself, 348. Either way, the temporal distance from the Ugaritic material is substantial.

[14] Day, God’s Conflict, 142; Angel, Chaos and the Son of Man, 5.

[15] G. W. Anderson, “Isaiah XXIV-XXVII Reconsidered,” SVT 9 (1963): 126, quoted in Day, God’s Conflict, 144; emphasis mine.

[16] Cf. Carol L. Meyers and Eric M. Meyers, Zechariah 9-14: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary, The Anchor Bible (New York: Doubleday, 1993), 15-16, who argue a fifth-century setting (18-26).