Building the Cathedral | 5. Construction

Making New Myths for a New Worldview

BREAKING GROUND

Ultimately, a creative mythology built from personal mythmaking is both an engagement with universal archetypes as well as a highly unique and idiosyncratic vision of a particular mind. Like a fingerprint, they are common to all humans, but no one is the same. Speaking to this distinctive aspect, Campbell compares creative myths to portraits of their mythmaker, revealing their personal essence, rooted in their own time and place of the world as it is. “A great portrait,” he says in Creative Mythology,

is a revelation, through the “empirical,” of the “intelligible” character of a being whose ground is beyond our comprehension. The work is an icon, so to say, of a spirituality true to this earth and to its life, where it is in the creatures of this world that the Delectable Mountains of our Pilgrim’s Progress are discovered, and where the radiance of the City of God is recognized as Man.[i]

In personal myth, the universal and particular collide. According to thinkers like Jung and Campbell, what links them is the unconscious, which is both personal and transpersonal, individual and collective. As such, creative myths are able to evoke the universal numinous by means of entirely novel and unique symbols.

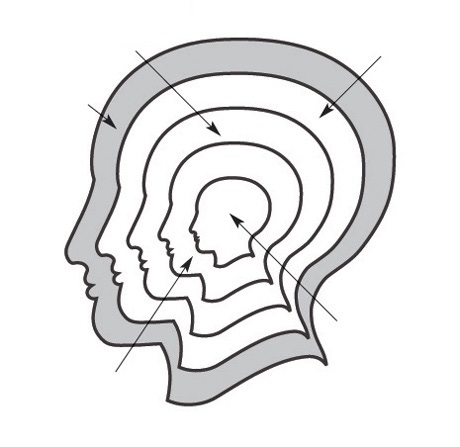

Our psyches are teeming with such inchoate images. Abiding just below the surface of consciousness are a whole host of psychic figures and personas: parts of your own personality, it turns out, just waiting to be engaged. A bit deeper and one encounters the great inherited archetypes, which need only the right symbolic representation to become activated in conscious awareness. It is the task of the creative imagination to do just this.

Initiating contact with such bedrock forces can be done in various ways. Dreams, active imagination, fantasy thinking, meditative trances, psychedelics/entheogens, mystical rapture, out-of-body experiences and the like can all produce profound and often transformative spiritual experiences. Even depressions, nervous breakdowns, and a “dark night of the soul” can prime the psyche for transformative resolutions of lasting power. All are means by which consciousness traverses beyond the normal, culturally-conditioned boundaries and into extreme states of the psyche for exploration and elaboration.

From these deep reserves spring the ever-refreshing waters of myth. If society’s “heap of broken images” were like salvaged bricks which one could use to build new structures, then here we come upon the original brick forge itself. The task is no longer to rework or rearrange, but to create. The goal is to generate entirely new mythical dynamics and symbolic forms through creative myth.

LETTING PSYCHE SPEAK

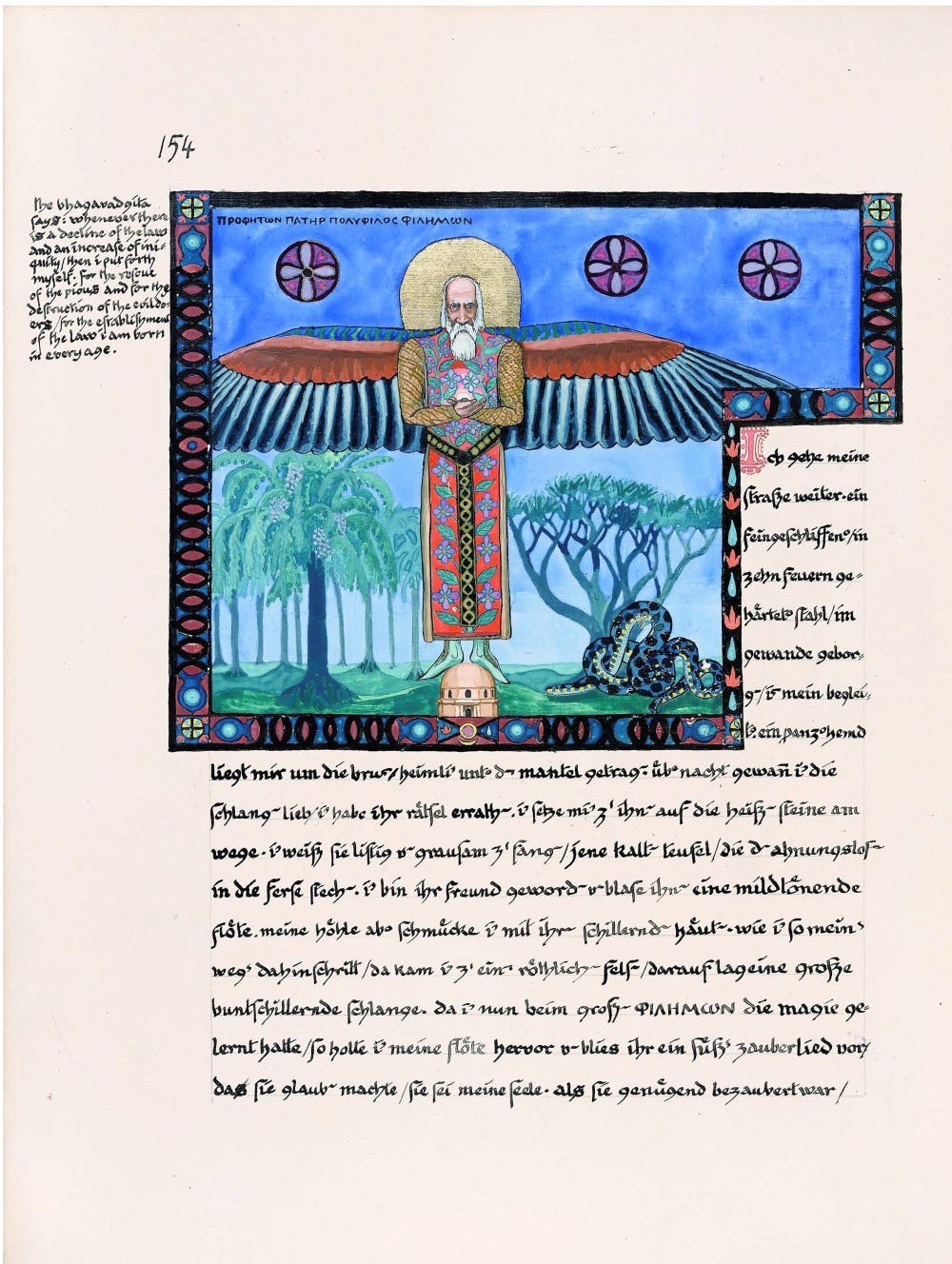

One method creative mythmakers, including Jung, have used to forge a fruitful link with the unconscious is by entering into discourse with distinct mythic personalities in their own unconscious. Letting your own psyche speak in its native voices can be a crucial bridge from your own inner dynamics and the dynamics playing themselves out in other psyches the world over.

Despite the seeming uniformity of our personalities—the apparently singular nature of our ego or self—such characters actually reside in all of us, and provide their own perspectives: ones usually more in touch with the unconscious world of archetypes. It was in this way that the character of Philemon appeared to Jung and served him as a sort of guide or guru figure with whom he could converse. Much of the Red Book consists of dialogue in this vein. Even in his conscious life, Jung divided himself into personality No. 1 and No. 2—No. 1 being the more rational and scientific, and No. 2. the more emotive and artistic.

Such a divvying up of the psyche is not at all uncommon, especially among great minds of talent or creativity. One thinks of the composer Robert Schumann, for instance, who wrote different styles of music under different pseudonyms he’d split off from himself: Florestan and Eusebius. Similarly, the writer and philosopher Søren Kierkegaard had a whole cast of characters in his head, each with his own perspective and stage of faith. Using them, he composed his Governance-inspired. “Authorship.”

Such inner personas are called “imagoes,” and can serve as a significant cast of characters in our personal myth. Dan McAdams writes:

Each of us consciously and unconsciously fashions main characters for our life stories. These characters function in our myths as if they were persons; hence, they are “personified.” And each has a somewhat exaggerated and one-dimensional form; hence, they are “idealized.” Our life stories may have one dominant imago or many.[ii]

Such imagoes might serve as genuinely mythic personalities in our creative mythology. Indeed, the tension of their often-disparate natures and interests is itself a form of the psyche seeking resolution and a harmony of opposites. To this end, we, as mythmakers, may direct the drama, channeling psychic tension into cathartic wisdom. Larsen notes:

In our personal mythology our story ultimately is told, and that story includes characters. The ego, I, or sense of self, whichever we choose to call it, is both immensely powerful and, at the same time, confusingly fragile. Our most important task, though, is the gaining of self-knowledge. More than merely actors, at best we are skilled directors. To put on the “good show” that comprises life we need to keep track of our inner cast.[iii]

In cases like this, personal myth, self-focused, bleeds imperceptibly into creative mythology, culture-oriented. You begin down the path of personal myth by crafting a meaningful interpretation of your life experience, drawing out the inner conflicts of your psyche and personifying them, such that, through their interplay and dialogue, you begin to find catharsis and resolution.

But as an expression emerging from your unconscious, your imagoes can be culturally important voices, dynamics others also feel. They may serve to populate your mythological pantheon—as daimons, perhaps, or demi-gods and goddesses, spirits, heroes or villains. As with any pantheon, the interactions between characters figures as an interplay of different fundamental forces vying for their own. Wisdom and self-knowledge lie in the harmonization of this polyphony of voices. McAdams writes:

A personal myth may be seen as a complex set of imaginal dialogues involving different imagoes developing over narrative time.[iv]

In this way, the most elementary function of personal mythmaking returns to our focus. Recall how Dan McAdams defined personal myth as, first and foremost, a story we construct “to bring together the different parts of ourselves and our lives into a purposeful and convincing whole.”[v] By working with our inner cast of characters in creative mythology, we do just this, bringing into alignment not just the episodes of our experience in meaningful story, but also the different parts of our psyche. In the process, we also externalize common tensions others likely share. Tensions between thinking and feeling, faith and doubt, worldly cares and transcendent aspirations, etc. Within you lies a microcosm of the entire world. Name the voices and set them talking. What they work out can bring both personal resolution and cultural insight.

NEW SYMBOLS

Personal myth and creative mythology are thus, as their names suggest, shot through with paradox. Myth, something traditionally elaborated by a collective, is somehow personal; something supposedly consisting of inherent archetypes is somehow creative. The consequence, in practice, is that any individual mythmaking will necessarily exhibit both common and idiosyncratic elements. Creative myths will include both universal and unique imagery, traditional and novel, in varying degrees and dynamics.

There are many ways this can occur. We have already considered exploring your own inner psychic dimensions as mythic figures. But what about unconscious material in the deeper strata of the collective unconscious? There are numerous ways we might play with archetypes, and explore entirely novel configurations and dynamics between symbols for their development.

Perhaps an ancient archetype is presented through a new symbol. Or the old, traditional symbol is set in conversation with an archetype or symbol only fully developed in an unrelated tradition, thus creating a new relationship or synthesis. Or, perhaps a newly emerging archetype that has been evolving in the collective unconscious for some time is finally given a symbolic representation. Creative mythology thus emerges out of old and new elements. Creative myth, says Campbell, is that which

springs from the unpredictable, unprecedented experience-in-illumination of an object by a subject, and the labor, then, of achieving communication of the effect. It is in this second, altogether secondary, technical phase of creative art, communication, that the general treasury, the dictionary so to say, of the world’s infinitely rich heritage of symbols, images, myth motives, and hero deeds may be called upon…to render the message. Or on the other hand, local, current, utterly novel themes and images may be used…[vi]

The plots of such new myths could be profound and revealing. What if Christ and Buddha were part of the same pantheon? What if Jehovah were a woman? What is the cosmological “map” of the DMT experience? The unconscious? What if angels were reincarnations? What if the Devil were redeemed back into Heaven?

Always ask, How do the old symbols speak to today? How do they seek to be transformed? Perhaps you write your own Gospel, or walk with God in the Garden. Campbell writes:

One way to activate the imagination is to propose to it a mythic image for contemplation and free development. Mythic images—from the Christian tradition, or from any other, for that matter, since they are all actually related—speak to very deep centers of the psyche. They came forth from the psyche originally and speak back to it. If you take in some traditional image proposed to you by your own religious tradition, your own society’s religious lore, proposing it to yourself for active imagination, without any strict game rules defining the sort of thoughts you must bear in mind in relation to it…letting your own psyche enjoy and develop it, you may find yourself running into imageries, experiences, and amplifications that do not fit exactly into the patterns of the tradition in which you have been trained.[vii]

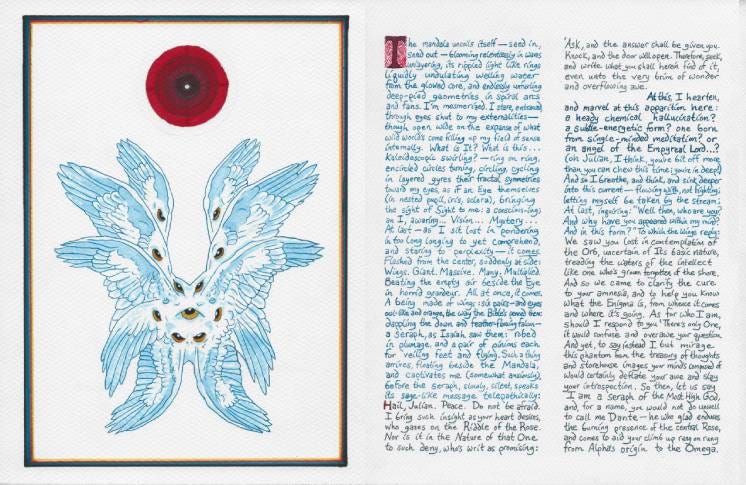

Otherwise, entirely new images and figures can be employed to express the numinous. Perhaps these come from dreams, intuitions, visions, or any of the number of “core experiences” mentioned earlier. Here your own, idiosyncratic experience with the unconscious comes into play. Perhaps you imagine a new conception of heavenly beings, a novel rendition of angels/devas called junnas. Or you mythologize the magical process by which plants grow—a force you call Elwis, alive in all things. Or you relate the wisdom of your guardian spirit, Bemniah. Or you write a drama about the passage of a soul from one body to the next, describing all the spiritual functionaries it meets in-between. Or you compose the Ultimate Mystery as a symphony of strings. Or paint your own soul. The world of myth is open to explore.

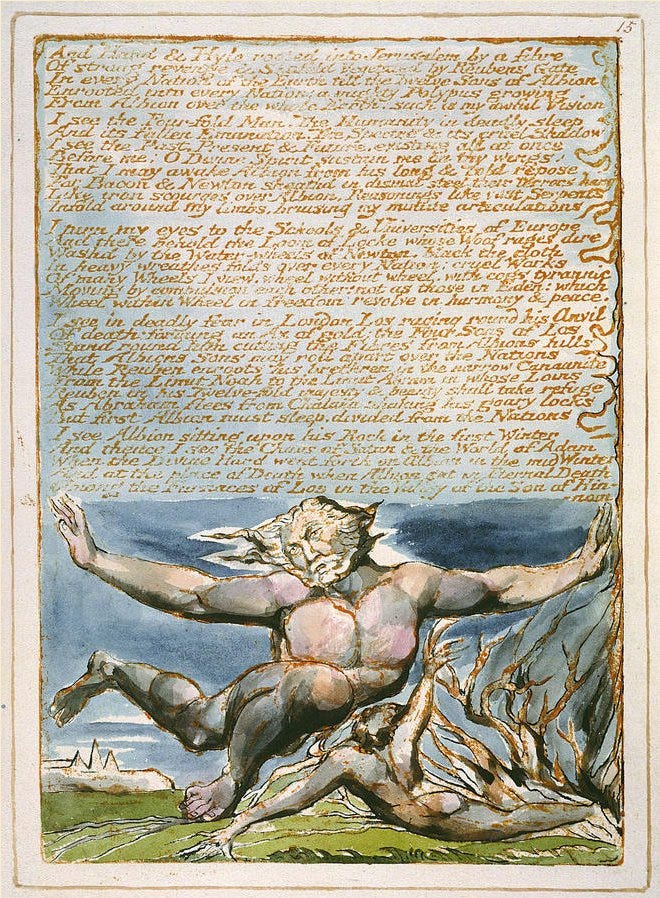

One of the most enduring examples of creative mythology at this level of originality is the work of poet and artist William Blake (1757–1827). Blake was a visionary in every sense of the word, possessed of daringly innovative ideas as well as a profound sensitivity for channeling unconscious material. A critic of conventional organized religion, he was committed to forging his own spiritual canon of inspired works rooted in his own experience. “As he developed his personal myth,” writes Leo Damrosch in his book Eternity’s Sunrise: The Imaginative World of William Blake, “it grew challengingly complicated and increasingly strange.”[viii] Eventually, though, a basic story is gleaned: Albion, the primordial man, has fallen asleep, and in becoming unconscious has lost his primeval wholeness. He fragments into four personalities, or Zoas. These are: Urizen, who represents rationalistic thinking and the oppressive imposition of law; Luvah, the nonrational emotions; Tharmas, the unifying power; and Urthona, the creative imagination.

Los (the name of Urthona in his fallen state) is the true hero of Blake’s myth. He is the craftsman, the forger, the creator, ever laboring at his smithy and challenging the relentlessly-codifying Urizen with revolutionary new forms. He labors at constructing a vast structure, the great art city of Golgonooza: a vast temple to the creative imagination. Like Albion, and the other Zoas in turn, Los also has a fragmented personality: a female emanation, Enitharmon, and a shadowy Spectre. Bringing all together in harmonious synthesis, he builds the great city of his imagination:

Therefore Los stands in London building Golgonooza,

Compelling his Spectre to labours mighty. Trembling in fear,

The Spectre weeps, but Los unmoved by tears or threats remains.

“I must create a system, or be enslaved by another man’s;

I will not reason and compare: my business is to create.”

So did Blake see his mythopoeic project: to create his own system, or else be fated to conform to one imposed upon him.

The system he creates is—true to the call of personal mythmaking—an expression of his own inner psychological workings. Many have noted the parallels between his inner cast of characters and those of the human psyche. Indeed, though some have been tempted to bring in Freud, Damrosch insightfully notes:

More congenial to Blake’s conception than Freud’s is Jung’s, which is not surprising, since Jung was interested in many of the same sources that Blake drew on. The Jungian category of thinking could be said to correspond to Urizen, intuition to Urthona, emotion to Luvah, and sense perception to Tharmas.[ix]

In this way, one sees a clear connection between Blake’s imagoes and Jung’s psychological types. More than that, the number four (the quaternity) was the symbol of psychic wholeness in Jung’s thought. (Jung, for his own part, built the Tower into four separate structures to represent this.) The Four Zoas of Albion’s psychic wholeness seem reminiscent of the same idea, while the presence of a feminine subpersonality and a shadowy double are all shockingly similar to Jung’s theories of the anima and shadow.

Clearly, Blake’s work taps into deep archetypal patterns. While boldly innovative, it is also elementary at the same time, reflecting in novel forms the ancient outlines of the human unconscious. In this way, he can invent from his imagination a veritable pantheon of deity-like forces in a creative epic—and yet, all the while, remain true to experience and the deep realities beyond our ken. Such is the nature of effective creative myth.

Because symbols are the language of the unconscious, to question the “veracity” or “truth-value” of such symbols is to miss the point. Myth speaks to the inner, psychic world of mankind, not the outer, objective world. As such, what matters is whether energies are activated or not, whether the new symbol is working to evoke the sense of the numinous, whether a given image works. If it does, it has something to say, something to teach us. If not, keep working with it, or try something else. Creative mythmaking is, like all creative work, an experimental process. The difference is that here, aesthetic interest is not the main goal, but rather numinous connection.

The Ultimate Mystery is just that—a profound and incomprehensible Mystery. Symbols can help to mediate our experience of it, but must never be taken as the thing itself. As the Buddhist expression goes, The finger pointing at the moon is not the moon. Symbols are tools for meditation, a means to approach the numinous. Engaging them creatively helps keep you in proper relationship to them. It is much harder to make an idol out of an image you yourself have crafted.

The threat to myth is always its turning to stone, its ossification, its concretization. This happens when one takes a symbol literally. It is thus objectified, and so you lose the dynamic play-exchange between the subjective and objective mindsets. The energy stops flowing, and living myth dies. Ultimately, the waste land we inhabit today came into being precisely because of this over-objectification of the world. We learned to think scientifically, and either lost or threw away our ability to think mythically.

This does not need to be the case. Science and myth can live together. Indeed, they must. Science has provided us an entirely new model of the universe. Psychologically, our image of the universe demands mythic expression, mythic integration. The objective world, too, must ultimately find a home in subjective mythic forms. Today, this great task likewise falls to the individual mythmaker as well. And so it is that this, too, provides a basis of material for the creative mythmaking—indeed, an urgent and important one.

A NEW COSMOS

Human beings have never stopped asking the perennial questions: Where did we come from? What are we made of? What is the shape and makeup of the universe? Such questions fill us with wonder, while their answers provide us a crucial sense of orientation.

These types of questions once found answers through myth. Today, we get them through science. Science has revealed to us the amazing grandeur of the skies and the unfathomable depths of the atom. It has told us our origins, and has provided an awesome map of our place in existence. Such things truly are the stuff of the tremendous and fascinating Ultimate Mystery. Campbell writes:

Not the neolithic peasant looking skyward with his hoe, not the old Sumerian priesthood watching planetary courses from the galleries of ziggurats, nor the modern clergyman quoting from a revised version of their book, but our own incredibly wonderful scientists today are the ones to teach us how to see: and if wonder and humility are the best vehicles to bear the soul to its hearth, I should think that a quiet Sunday morning spent at home in controlled meditation on a picture book of the galaxies might be an auspicious start for a voyage.[x]

Unfortunately, the incredible glories of our world revealed by science have not yet been meaningfully integrated into the collective psyche. Indeed, for many people, the new vision of the universe is mainly that of a vast, careless void, which came into being by chance and goes onward without reason or purpose to direct it. They feel today more or less as Blaise Pascal did when the implications of the new scientific discoveries were just beginning to sink in:

When I consider the short duration of my life, swallowed up in an eternity before and after, the little space I fill engulfed in the infinite immensity of spaces whereof I know nothing, and which know nothing of me, I am terrified. The eternal silence of these infinite spaces frightens me.

Experienced in this way, the universe is only terrible, and life within it, but “a tale / Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, / Signifying nothing.” It is, in short, meaningless.

This does not need to be the case. The reason for this unfortunate prevalence of despair stems from the fact that our new understanding of the universe has not been meaningfully integrated into our collective consciousness. That is to say, it has not yet been rendered mythologically.

Science is a powerful method for understanding objective reality. Indeed, it is by far the most powerful tool ever devised by mankind for this end. What it is not good at is communicating that reality in ways that speak to our subjective experience, that render those truths into something emotionally and psychologically significant. This is what myth does.

Psychologically, humans crave story. We connect with narrative structures, with clear meanings and morals, and the beauty of a compelling tale well-told. This is why, for millennia, people turned to their mythic stories for satisfying answers to life’s profound questions. Science, by contrast, is not interested in such things. It dwells in questions, not answers, and its focus is objective fact, without regard for how these facts are emotionally or psychologically integrated into a subjective psyche.

The result is that, today, we have a great many facts about the universe but no meaningful story of it. As yet, our new model of the cosmos has not found any definitive expression in the mythic modality. So long as this is the case, people will continue to experience the universe as meaningless. Because such a perspective is psychologically so taxing and emotionally unfulfilling, it is understandable why many continue to hold on to entirely outmoded mythic systems. A world made in six days, talking snakes, a boat holding all the world’s animals. These are symbolically-rich myths; but, at the level of explanation for objective realities, are no more than fairy-tales. Still, even intelligent people will maintain them as literal truths if it means avoiding the only alternative: a set of facts detailing a bleak, careless universe, undirected, stretching shudderingly into a yawning infinity. A silly myth is better than a convincing chaos.

Clearly, what is desperately needed today is an account of the universe that is both in accord with our scientific understanding of it and also psychologically fulfilling. That is, we need a new mythological rendering of the cosmos, one that is right both objectively and subjectively. As ever, this is the task for poets and artists, not scientists, for it must speak to the heart, not just the head. It must be beautiful, not simply correct. As such, it is the endeavor of personal mythmaking—one of finding a new, mythic language for creation.

Fortunately, the subject matter doesn’t disappoint. Its majesty and sublime scale beg to be rendered mythically. In the heavens, sprawling purple clouds that span for eons give birth to stars. Their vast explosions sow the cosmos with elemental seeds. Life emerges in the depths. Epochs of magic metamorphosis change fish to birds. A mystical code in every cell unfolds its intricate design. Consciousness emerges from the dark—to learn, to love, to create.

Here, the task is not so much the crafting of new symbols, since the subject matter is physical and not metaphysical, immanent reality and not transcendent archetypes. What we need, rather, is a new narrative, a new Genesis. A shared mythic telling that relates the physical processes as sacred history. Our culture lacks a creation myth about the Ultimate Mystery. We do not lack a Story, only its proper telling. We do not lack a great cosmological myth—only mythmakers.

For those who take up the call of creative mythology, an epic awaits to be told. Ironically, it is far grander and more sublime than we could ever have imagined. Science has revealed to us a universe of incomprehensible glory and splendor. It falls to us to lift this from the dry prose of textbooks into the solemn grandeur of poetic myth. Our greatest story has yet to be told. To do so is not just the most auspicious task for artists of any generation. It is also a service to humanity—to call people back to inhabit their world as it is. To help them feel at home in the universe again. And so, to return a sense of meaning to existence, sacralizing the heavens once more and returning to Earth its proper sense of sacredness.

Doing so would free people at last to leave behind their childish creation tales for something both grander and truer. More than that, it would dissipate the lies allowing so many to desecrate and destroy the Earth. A resacralized universe is one to be revered, not raped for raw materials. A New Myth is possible—one with new heavens and a new Earth, pervaded by the glory of the mysterium tremendum et fascinans.

In this way, through personal myth, the cosmological function of myth could be fulfilled: to present a total image of the universe through which the ultimate mystery manifests. We only await the poets to come who will commit themselves to the task. The personal mythmaker is called, ultimately, to communicate the universe and transform the world—a much broader and bigger calling than has hitherto been imaged for such work. But so it is. Personal mythmaking is the key to bringing meaning back into the world. It begins with the individual, but very quickly expands, for those who feel so called, into the social realm—to articulate new, living mythic symbols and even a meaningful vision of the cosmos.

However, to do so, personal myth must move beyond an individual subjective consciousness and out into the collective consciousness. That is, it must become objective, and so externalized. Thus we come to a crossroads. How deep are you to go with this mythmaking process? How driven are you to explore the possibilities of personal myth and your own potential for self-actualization? How far do you feel called—or fated—down the path of individuation, of carving out your own unique expressions of archetypal forms? Have you had a numinous experience? The sense of the Great Mystery “sweeping like a gentle tide, pervading the mind with a tranquil mood of deepest worship,” or perhaps a “sudden eruption up from the depths of the soul” more like Jung’s? Are these the secret gems of a secret personal myth, or do they call out to become something more? something you feel inspired to share with the world somehow? to work these experiences into a personal myth that’s something more than personal—perhaps, even, a seed of the New Myth not yet on the horizon?

THE OPUS

It is one thing to maintain a personal religion as a collection of personally-meaningful symbols, ideas, memories, etc. It’s a rather different thing to actually convert these from the blueprint stage in your head to a finished building out in the world. To do this requires externalizing them into some kind of container—to craft something tangible, as Jung and Blake did, and thereby change the world.

This is truly the task of building your cathedral.

At a certain point, for certain people, personal myth demands outward expression. These experiences and formulations compel some kind of externalization, their making real in the world in some physical form. They long to be communicated to others. The communication of such myths is a key factor of Campbell’s definition of creative mythology. “In what I am calling “creative” mythology,” he writes,

the individual has had an experience of his own—of order, horror, beauty, or even mere exhilaration—which he seeks to communicate through signs; and if his realization has been of a certain depth and import, his communication will have the value and force of living myth—for those, that is to say, who receive and respond to it themselves, with recognition, uncoerced.[xi]

The precise motivation behind this urge to share will vary among individuals. It may even vary over time for the same person. Perhaps the drive is toward simple self-expression, the way the early Modernist artists sought to express themselves and their biographies through art. Or it is pure therapy, a psychiatric process for working out the unconscious stirrings within. Perhaps it is felt with all the compulsion of an exorcism—a need to purge oneself of built-up spiritual forces. Or it is experienced as prophecy: a channeling of the divine into the world for the world’s edification and enlightenment. Maybe it is part of a more intentional social project, to meet the urgent demand of the world for living myth, such as the crafting of a collective cosmology. Or maybe it is entirely unclear what and why you feel the need to express such things. Perhaps you will learn what it all means afterwards, after it has been externalized and you can take it all in for what it is.

Whatever the reason behind the urge to communicate one’s mythology, the project will stem from a similar origin and lead to a similar outcome in any case. You have had a meaningful insight into life, an intuition about the Ultimate Reality, and now must put it into form in order to share it with others. It must therefore take some tangible shape: book(s), painting(s), sculpture(s), song(s)—the possibilities are as endless as the media that might be used to render them.

This is called the opus of the creative mythmaker, and whatever form it takes, it must work to contain the mythic material and communicate it effectively to others. Bond writes: “The work, the opus, the labor provides a form that holds inner and outer experience together in the vessel of meaning.”[xii] Through the opus, the creative mythologist converts their individual experiences of the Ultimate Mystery into a coherent container of psychic power. It does this by translating the experience into a language that best communicates the ineffable qualities of the numinous experience into images and symbols.

Like all inspiration, the original experience may have been immediate and passively received, but the translation process itself is a reflective, conscious activity. Indeed, it may be long and arduous, with many fits and starts, just to communicate. This period can be immensely fruitful for the mythmaker, as an opportunity to further clarify and flesh out what in the “blueprint” phase remained hazy and uncertain. Ultimately, says Bond, “the cultural form that the myth takes requires a conscious labor, an opus, but the vision itself is a product of psyche.”[xiii] Whoever would seek to do this must become an artist of their myth.

Regardless of what else such creations might be, there is an undeniable link between this process and the work of the artist. Simply put, the external formation of non-traditional, personally-resonant mythic imagery is an imaginative aesthetic enterprise. The inner voice in Jung’s head recognized this even before he did. To fashion a creative myth is to make a work of art of some kind or another.

Art, of course, is hard to define and pin down. Things can be art even while serving other, perhaps more primary functions. In fact, most of the pictorial “art” from history, so-called, was originally engaged religiously, as objects for meditation and religious contemplation. What one person sees as a work of art might, for another person, be seen as a religious icon. Neither are wrong. Jung saw what he was doing as something other than art. That does not stop millions of people from admiring his Red Book as an aesthetic object.

The relationship between art and religious material culture is rich and deep, and goes back to the dawn of time. Cave paintings, the very first examples of art we know of, are believed to have been primarily used for magical and shamanistic purposes. The first poets told mythic stories of gods and spirits; prophecy itself was poetry, and poetry prophecy. The very word “inspiration” (the process of being inhabited or influenced by spiritual forces) still relates to both religious authority (an “inspired” scripture) and aesthetic artfulness and ingenuity (an “inspired” work). Art and mythmaking are intricately bound, and always have been.

Indeed, Campbell has suggested that the artist and the mystic share a fundamental orientation to the world. The very “yes” we say to our life and consequently the world is, he claims, the same “yes” to life that inspires the artist to create. For Campbell, the true artist is neither teacher nor activist, neither provocateur nor marketer; the true artist is pushing nothing—only presenting the world as it is in an expression of that pure inner gratitude for being. Thus “the first function of art is exactly that which I have already named as the first function of mythology…”[xiv] The artist performs the metaphysical function of myth. In this way, the true artist is, fundamentally, a mystic.

In a world now devoid of religious seers, shamans, and prophets, it falls upon the mythic artist to continue the mystical function of mythmaking in the world. This they do by translating their personal experience of the holy into outward symbols that can serve as evocations and suggestions to others for how they can experience the holy for themselves. They play the midwife to others’ spiritual development, working by indirect means to ignite a subjective connection with the Source. Campbell writes:

we move—each—in two worlds: the inward of our own awareness, and an outward of participation in the history of our time and place. …Creative artists…are mankind’s awakeners to recollection: summoners of our outward mind to conscious contact with ourselves, not as participants in this or that morsel of history, but as spirit, in the consciousness of being. Their task, therefore, is to communicate directly from one inward world to another, in such a way that an actual shock of experience will have been rendered: not a mere statement for the information or persuasion of the brain, but an effective communication across the void of space and time from one center of consciousness to another. …The mythogenetic zone today is in the individual in contact with his own interior life, communicating through his art with those “out there.”[xv]

Creative mythology thus entails more than simply “getting the point across” about a numinous or sacred experience. It is more than a recounting of an event or an essayistic description of what you think it all means. Rather, creative mythology is evocative—it calls out something from within the audience. It employs the imagistic language of symbols to work on the inner worlds of the audience to help facilitate their own wonder and to inspire their own imaginations. It does this, Jung might say, by activating the archetypes latent in the audience, and thus arousing their own organic response of mystery and wonder.

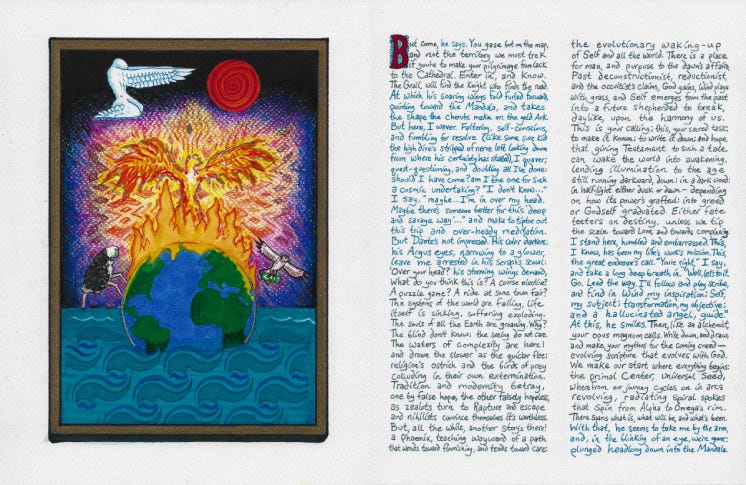

Creative mythologies thus aspire to the same sort of reception that religious myth and ritual sought to evoke, but no longer can. But what is dead in the traditions can emerge with all vitality in the living myths of today’s creative mythologists. No doubt there are still many people who, when opening the Bible, are filled with excitement and a sense of wonder before a sacred, numinous text. However, such an experience is becoming less and less common as the symbols therein and the mythic system they inform lose their grip on the imagination. They are more likely to be encountered as old, overly familiar, outdated, dead. Opening the Red Book, however, or an illuminated copy of Blake’s Jerusalem, is a very different experience. You immediately feel an electric pulse, of wonder and uncertainty, interest and curiosity. Indeed, you feel the tug of the mysterium tremendum et fascinans. Here is living water. Not necessarily because it is more true than ancient Scripture, but only because the symbols are still speaking, still dynamic, still vital. Here, one feels, is a genuine personal encounter with the Source, whatever that may mean. As such, it is compelling, fascinating, captivating. It activates the archetypal energies in a way old systems no longer can.

Whatever the specific driving motivation for the mythologist to create, this is ultimately the end one strives toward. Creative myth causes living water to flow once more in our spiritual desert. For those receptive to it, it opens a portal to the deep unconscious Source of myth, which, in religious traditions—now dead and ossified—had remained barred. This is the meaningful vocation of the creative mythmaker.

MYTHS OF PURPOSE, PURPOSE IN MYTH

Such tasks are clearly of great importance—especially today, when meaning is so desperately sought, but direction so unclear. The influence of the contemporary mythmaker, then, could not be overstated. Their work can and will literally change the world.

And so it is that personal mythmaking of the most elementary kind discussed at the outset loops back to such high-flown creative mythmaking which includes the crafting of artistic mythologies for the world. That is, for some, the communication of mythic images becomes for them a goal of immense personal importance. For such people, the commitment to the project of crafting and sharing their creative myth is itself the anchor of their life story—the imaginative act that frames their life as an integrated and purposeful whole. Communicating their personal experience of the sacred becomes the driving motivator of their personal narrative. What is my meaning? To make myths and share them. One’s personal myth is being a creative myth-maker.

Our horizons tell our story, and presently they are full of shallow monuments to only our baser drives and of empty of all meaningful endeavor. Though the skylines rise with soaring peaks, we live in a spiritual desert, a barren wasteland stretching forward without interruption. To replenish that desert, to fill the world again with myth, to activate in others the sense of meaning and wonder—this, surely, is a worthy task. Here we spiral back to the psychological function of myth: producing the New Myth is indeed a thing to live for, a mythic seizure, something to motivate us—not just for ourselves, but for the world in which we live. In this way, personal myth ties us back to our broader context, to fulfill the psychological function of myth in its most robust expression:

the centering and unfolding of the individual in integrity, in accord with himself (the microcosm), culture (the mesocosm), the universe (the macrocosm), and that awesome ultimate mystery which is both beyond and within himself and all things.[xvi]

Such is the calling of contemporary mythmaking, which strives, ultimately, toward that New Myth beyond the horizon, the one that will renew people’s sense of meaning and place, the one that will gather them together in shared aspiration, the one that will motivate a new and renewed civilization.

NEXT: 6. THE MASTER PLAN

Buy a print copy here:

NOTES

[i] Campbell, Creative Mythology, 35-36.

[ii] McAdams, The Stories We Live By, 122.

[iii] Larsen, Mythic Imagination, 204.

[iv] The Stories We Live By, 131.

[v] The Stories We Live By, 12.

[vi] Creative Mythology, 40.

[vii] Campbell, Thou Art That, 38-39.

[viii] Leo Damrosch (2015) Eternity’s Sunrise: The Imaginative World of William Blake (Yale University Press, New Haven, CT), 155.

[ix] Eternity’s Sunrise, 156.

[x] Creative Mythology, 614.

[xi] Creative Mythology, 4.

[xii] Bond, Living Myth, 138.

[xiii] Living Myth, 131.

[xiv] Campbell, The Mythic Dimension, 238.

[xv] Creative Mythology, 92-93.

[xvi] Creative Mythology, 6.

I love reading your writing, thanks Brendon! Feels so on point for what is needed today - alive (in much the same quality that you're pointing towards Blake and Jung's personal myths having).