Building the Cathedral | 1. Surveying

What Myth Are We Living?

HORIZONS

The renowned comparative mythologist Joseph Campbell once noted: “If you want to see what a society really believes in, look at what the biggest buildings on the horizon are dedicated to.” Our horizons tell our stories; skylines speak.

In the 13th century, at the peak of medieval piety, the air was flooded with countless collective efforts: mighty, multi-generational enterprises, accreting slowly: communal prayers in stone—the great cathedrals—rising heavenward…

Today, our cities pronounce a different set of values. Sleek skyscrapers loom up from the financial districts of the world like obelisks of glass; stark office-buildings and luxury apartment-complexes cast their concrete shadows onto the streets below; and, touching the clouds, metallic monuments to global trade shimmer like crystal mirrors of the empty air.

Our horizons tell our stories; they are the silhouettes left by our myths—which is to say, our dreams, our aspirations, our great purposes. Campbell also noted: “The rise and fall of civilizations in the long, broad course of history can be seen to have been largely a function of the integrity and cogency of their supporting canons of myth; for not authority but aspiration is the motivator, builder, and transformer of civilization.”[i]

The question then naturally arises: What is our aspiration?

What motivates us, today, in the 21st century?

What is our purpose?

What is our myth?

The change in horizons tells its own story. Like the horizon, it is big, and like all big stories, it is somewhat overtold—though no less true for that. Like a skyline, the story has many components, but one broad shape. So, whether you focus on this part or that—the scientific revolution, say, or industrialization, secularization, rationalism, statism, capitalism—the takeaway impression is still the same. From Saint-Denis to St. Regis, from Aachen to Aon, one reads in the difference a long, clear tale. It is a story of disenchantment—of losing the soaring magic and meaning of our lives to the banality of things: to commerce, comfort, and commodity.

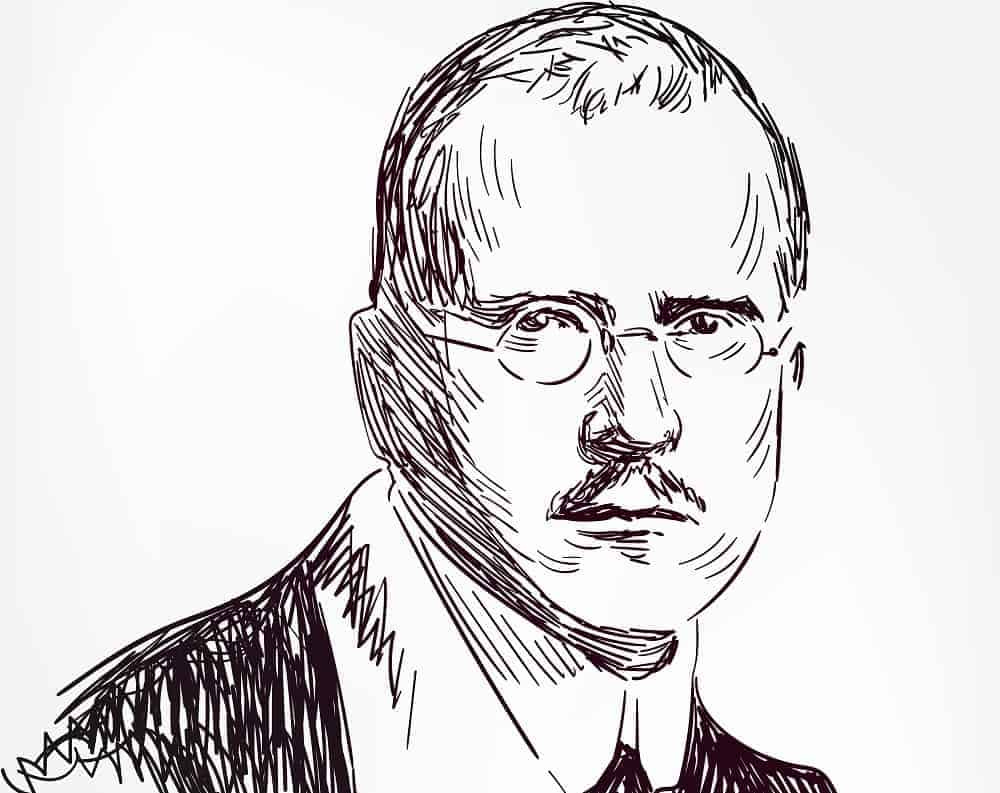

And myth? “In what myth does man live nowadays?” Carl Jung, the pioneering psychologist, asked himself a decade into the 20th century.

“In the Christian myth, the answer might be,” he proposed from a Europe still nominally Christian. Though, “Christian Europe,” even by Jung’s time, was a mostly-spent force. The old moral God, whose myth of Adam’s sin and Christ’s redemption once held the Western world in thrall, was dead (as Nietzsche had recognized a generation earlier), even though His shadow would persist on the Earth for some time. No, the epoch of the old religion was drawing to its close. And the Christian myth?

The introspective psychologist wrestled internally:

“Do you live in it?” I asked myself.

To be honest, the answer was no. For me, it is not what I live by.

“Then do we no longer have any myth?”

“No, evidently we no longer have any myth.”

“But then what is your myth—the myth in which you do live?”

At this point the dialogue with myself became uncomfortable, and I stopped thinking. I had reached a dead end.[ii]

What is your myth—the myth in which you do live…?

Human beings are mythic creatures. It is our myths that inspire our most meaningful and enduring actions. It is our myths that build and motivate our civilizations, that lead us to forge pyramids and cathedrals in communal efforts spanning centuries. So what does it mean for us today, when myth itself seems to have reached a dead end? What does it mean for each of us, individually, that our cultural myth is no longer living? From what are you to derive your sense of purpose, direction, and motivation?

What is your myth?

Jung was at a crisis point in his life when he realized the absence of myth in his life. It was, he would later write in his memoir Memories, Dreams, Reflections,[iii] a “period of inner uncertainty” and “disorientation,” a time during which he felt “suspended in mid-air,” without a clear footing or foundation for his existence. In this state of crisis, writes Jung,

I was driven to ask myself in all seriousness: “What is the myth you are living?”

I found no answer to this question, and had to admit that I was not living with a myth, or even in a myth, but rather in an uncertain cloud of theoretical possibilities which I was beginning to regard with increasing distrust…

So, in the most natural way, I took it upon myself to get to know “my” myth, and I regarded this as the task of tasks…[iv]

In 1912, the psychologist’s psychic turmoil had begun to manifest in a series of strange dreams. Bizarre images rattled his unconscious—experiences similar, he knew, to those recounted by the psychotic patients he treated at the asylum where he had worked. Jung was concerned. But, rather than run from the problem, the intrepid psychoanalyst committed himself to confronting the issue head-on. After all, how could he expect his patients to work through their psychic disturbances if their own doctor couldn’t work through his?

Seeing no other way, all he could do was give in to his intuition and let instinct guide him to some resolution. “I consciously submitted myself,” he says, “to the impulses of the unconscious.”[v] Finding no living myth for himself in the spiritual desert which modern, secular society had become, Jung turned to the last font that still seemed to flow with any vital energies: his own inner world—his experience, his dreams, his fantasies, the pressing material of his own unconscious.

When he did, a flash of inspiration eventually struck. A childhood memory rose: a memory of…playing…

…building with blocks…

Simple though it was, the memory stirred him. Amidst a spiritual desert, Jung felt he had struck a spring of still-living water within himself. “There is still life in these things,” he marveled. “The small boy is still around, and possesses a creative life which I lack.”[vi] True to his purpose, Jung gave himself over to the impulse—to see what it might yield.

The 37-year-old doctor began to play.

I started building: cottages, a castle, a whole village. The church was still missing, so I made a square building with a hexagonal drum on top of it, and a dome. A church also requires an altar, but I hesitated to build that. Preoccupied with the question of how I could approach this task, I was walking along the lake as usual one day, picking up stones out of the gravel on the shore. Suddenly I caught sight of a red stone, a four-sided pyramid about an inch and a half high. It was a fragment of stone which had been polished into this shape by the action of the water—a pure product of chance. I knew at once: this was the altar![vii]

Jung let himself become lost in play, tapping into his inner creative child, building cathedrals…

Of course, being a scientist, he was also well aware what an odd figure he now struck—a grown man playing with stones. His conscious, critical perspective loudly resisted. “Naturally,” he writes,

I thought about the significance of what I was doing, and asked myself, “Now, really, what are you about? You are building a small town, and doing it as if it were a rite!” I had no answer to my question, only the inner certainty that I was on the way to discovering my own myth.[viii]

Jung refused to let critical self-awareness stop him. About his play, he was quite serious. The dignified psychologist kept playing with his rocks on the beach.

And, indeed, his little game of enchantment paid off. “In the course of this activity,” he writes, “my thought clarified, and I was able to grasp the fantasies whose presence in myself I dimly felt.”[ix] His “building game,” it turned out, was “only a beginning.” It now unleashed a torrent of dreams and images from his unconscious. Play had broken the dam, and the spring became a river. So, like before with his stones, Jung channeled it into construction and creativity.

Transcribing the content of his new mental visions onto the pages of a large red folio journal, Jung would paint his symbolic dreams in vivid color, with an accompanying script of intricate calligraphy worthy of the finest illuminated manuscripts. Fantastic scenes, and even distinct unconscious personas—such as a wise guide-figure named Philemon, whom he hauntingly depicted flying aloft on kingfisher’s wings—now populated the pages of a strange, personal scripture: Jung’s Red Book, inspired by his unconscious.

Such symbolic figures were representative of “the fund of unconscious images which fatally confuse the mental patient,” Jung knew. “But it is also the matrix of a mythopoeic [mythmaking] imagination which had vanished from our rational age.”[x] The process of reconnecting with this matrix was precisely what Jung needed to explore his myth.

As before, he persisted with his constructive project even as his rational mind retained a critical awareness that cast doubt on his enterprise. “When I was writing down these fantasies,” he remembers,

I once asked myself, “What am I really doing? Certainly this has nothing to do with science. But then what is it?” Whereupon a voice within me said, “It is art.” I was astonished. It had never entered my head that what I was writing had any connection with art.[xi]

Though Jung had not set out to produce art, and would later give up the Red Book for a more analytical approach to his visions, he would never leave behind creative construction as a means of exploring and articulating his myth. Indeed, such expression, he ultimately recognized, was his myth. Finding some way to make conscious and material the images formerly hidden and invisible in the unconscious was itself his life’s mission, his personal myth. As he says succinctly in the very first sentence of his memoir, “My life is a story of the self-realization of the unconscious.” It is ultimately to that end that he labored. That was the story and the meaning of his life.

Once hit upon, Jung expressed that myth in all he did, from the Red Book, to his scientific writings, to his own autobiography. As it turned out, though, his true medium of choice was not in these, but already hinted at earlier, in that initial spark of intuition which first broke open his unconscious for exploration:

Building.

Playing with stones had put Jung back in touch with his mythopoeic imagination; eventually, he would hew his very myth through them. “Gradually,” he writes,

through my scientific work, I was able to put my fantasies and the contents of the unconscious on a solid footing. Words and paper, however, did not seem real enough to me; something more was needed. I had to achieve a kind of representation in stone of my innermost thoughts and of the knowledge I had acquired. Or, to put it another way, I had to make a confession of faith in stone. That was the beginning of the “Tower,” the house which I built for myself at Bollingen.[xii]

For the remainder of his life, Jung worked the stones at Bollingen into a mighty structure that contained, in architectural form, the very essence of his person. “From the beginning,” he writes, “I felt the Tower as in some way a place of maturation—a maternal womb or a maternal figure in which I could become what I was, what I am and will be. It gave me the feeling as if I were being reborn in stone.”[xiii] From the symbolic reliefs Jung carved into its walls, to the schematic layout that finally materialized (“only afterward did I see how all the parts fitted together”),[xiv] Jung labored to present his personal myth in monumental rock.

Horizons tell our stories; skylines speak. At Bollingen, a novel structure rose into the air: Jung’s Tower, telling his. At the building’s core, the Swiss psychologist built a private chapel—a quiet meditation room, to which he alone kept the key. (The land, after all, had originally been owned by a nearby monastery…)

Jung was building his cathedral.

Hewn from the raw material of his own experience, this was one man’s temple, a shrine to the God he had discovered—and dedicated his life to continue discovering—within himself.

What does it mean to work on something like that? What does it mean to give yourself to a project that demands your complete commitment, that incorporates and valorizes the totality of who you are?

The builders of the 13th century aspired to a God above; what about cathedrals to the God within? What role might they play in a world otherwise given over to the smallness of material and mundane things—to the daily grind of getting and spending?

What could our horizons look like?

An individual is unique, true; but some can be exemplary. Finding your own way can help lead others to theirs. For all his emphasis on “individuation”—that demanding task of carving for yourself in the world, and learning to express your own individual vision—Jung never sought monastic renunciation or turned his back on the world. Indeed, it was largely the prospect of being able to help his patients by means of his experience that drove him to gaining wisdom of the unconscious. He was, first and foremost, a psychiatrist: a “doctor of the soul.” His life’s work was his medicine. Today, Jung’s methods are employed around the world; his writings have become the seminal canon for a whole field, to which new generations are continually adding. In this way, Jung’s Tower is itself only part of a much larger cathedral, one that is still being built and developed through a vast communal effort.

After a long and arduous psychological process, Carl Jung eventually found the answers he was looking for. Individually, on his own, he had succeeded in re-centering himself in myth and finding true purpose in the work of a lifetime. By looking beyond his culture’s depleted religious system and developing his own personal myth, Jung had found a way back to the vital source, to the unified unconscious Self, to what the religions call “God”—and one that led directly through his own biography. This labor activated a community, and continues to provide tools for personal growth even today.

Now, almost a hundred years later, Jung’s “task of tasks” has become ours—and one more urgent and necessary than ever. The last collective myth has receded even further; the shadow of God grows dim; and, in the sky, our Earth’s horizons darken with ever-taller metropolitan monoliths to Money: the only generally-recognized worth in a world shorn of higher purposes. If we are to find true meaning and fulfilment, there is no longer any choice now but to look within, as Jung did—not just for ourselves, but for the world. And, as for him, the way lies through the development of your personal myth.

PERSONAL MYTH

So, what exactly is personal myth? In the decades since Jung first introduced it, the term has gone on to acquire a somewhat diffuse array of meanings as subsequent generations of psychologists and mythologists have developed the idea in slightly different directions. Nevertheless, in spite of this diversity, there are a number of key elements about which all more or less agree.

Among these consensus points is the impetus for personal myth: namely, the growing inability of cultural myth (i.e., traditional religions) to provide people a sense of meaning, and the transference of that responsibility to the individual. As Stephen Larsen, one of Joseph Campbell’s protégées and author of The Mythic Imagination: The Quest for Meaning Through Personal Mythology, puts it: “Mythology was, perforce, collective mythology. But in our modern times these forms have relaxed their collective grip on the psyche, placing the burden for a meaningful experience of the universe on the individual person.”[xv] Indeed, as Campbell himself wrote, “[W]e can no longer look to communities for the generation of myth. The mythogenetic zone today is the individual in contact with his own interior life…”[xvi] Some form of this sentiment is shared by virtually all writers on personal myth.

This idea leads directly to another universally-recognized feature of personal myth: Because the locus of myth and mythmaking has shifted from the inherited cultural tradition to the individual’s inner life, it is in our own experience that we must seek the inspiration and material from which to craft our myth. So, as Dan McAdams says in The Stories We Live By: Personal Myths and the Making of the Self, “The personal myth is…a sacred story that embodies personal truth. To say that a personal myth is ‘sacred’ is to suggest that a personal myth deals with those ultimate questions that preoccupy theologians and philosophers.”[xvii] The traditional idea of “sacred history” is thus converted to something like “sacred biography.” Meaning is found not through participation in a group’s relation to the divine (e.g., the Church, the people of Israel, etc.), but in seeing your own story as meaningful, in forging your own link to the sacred.

At a basic level, then, a personal myth can be understood as an individual’s narrative of meaning, developed out of their own experience, which fulfills for them what cultural myths once provided but no longer can. In their book Personal Mythology, David Feinstein and Stanley Krippner write:

Personal myths speak to the broad concerns of identity (Who am I?), direction (Where am I going?), and purpose (Why am I going there?). For an internal system of images, narratives, and emotions to be called a personal myth, it must address at least one of the core concerns of human existence, the traditional domains of cultural mythology.[xviii]

If personal myths effectively operate as individual substitutes for cultural myths, we will need to understand what functions cultural myths used to perform if we are to see how these might be effectively transferred to the sphere of the individual. Here Feinstein and Krippner rightly direct us to Joseph Campbell’s oft-cited “four functions of mythology” for guidance.

According to Campbell, myths fulfill what he calls a psychological, metaphysical, cosmological, and a sociological function:

Myth’s psychological function is to center the individual, carry them through the stages of development, and harmonize them with their world.

Myth’s metaphysical function is to awaken in the individual a sense of awe and gratitude for the ultimate mystery, reconciling them to reality as it is.

Myth’s cosmological function is to present a total image of the universe through which the ultimate mystery manifests.

Myth’s sociological function is to validate and maintain a certain moral order of laws for living with others in society. [xix]

In premodern/traditional societies, the inherited cultural myth-systems functioned (more or less) successfully on all of the levels, providing individuals guidance through 1) their life’s developmental crises and transformations, 2) a framework for relating themselves to the Ultimate Mystery, 3) an explanatory orientation for meaningfully navigating their world, and 4) a sense of how to treat other individuals in their community. When all of these needs are met and harmoniously integrated, the individual will feel in alignment with herself and her world: a state experienced as a sense of meaning and wholeness.

As noted, however, the transformation of our horizons has reconfigured society along entirely different lines from the old premodern, mythic ones—a process completed in the 20th century, though set in motion much earlier. As of yet, no one has found a means to put the pieces back together in our new world—that is, to re-integrate a meaningful mythic existence with the developments of modern life. I believe that personal myth offers us a path to do just this.

However, it will require us to see the bigger picture. To date, no writers on the topic have been so bold in their suggestions as I would like to be. Most tend to speak as though personal myth were just another form of therapy, its impacts confined entirely to a patient’s psyche. Recall, for instance, how Feinstein and Krippner suggest that a personal myth, if it is to warrant the title, must address “at least one” of Campbell’s four functions. But why so few? Why can’t personal mythmaking address all of myth’s functions?

It is perhaps not surprising that, as psychologists, most writers on the topic seem to presume that it is the psychological function which is to be addressed by personal myth. A few of the bolder ones incorporate the metaphysical function as well, but none go any further. Some nod to the prospect that a new cultural myth is on the horizon, but decline to imagine what it might be or how it might come into being. Even Campbell, content to accept the modern secular world as a kind of “neutral” zone in which individuals work out their myths for themselves, does not venture to consider how mythopoesis could re-enchant more than just the personal psyche.

But, what if it can?

Personal myth has the power to transform individual lives, as it did Jung’s, by reconnecting them with the mythic forces of meaning, encountered directly. Indeed, in the spiritual desert we inhabit today, this is quickly becoming the only authentic, non-regressive path for reclaiming that sense of meaning and coherence which myth once provided. However, just because this kind of myth is personal—that is, rooted in our own experience and not within an inherited set of traditions and customs—does not mean that the practice of personal myth needs to be isolated, lonely, an entirely subjective affair cut off from community and the rest of the world. Certainly Jung’s personal mythmaking had a profound impact on society. What would it look like if personal mythmaking operated in community? What if shared and safe spaces existed in which developing your personal myth was cultivated and encouraged? What could inter-personal myth look like in such supportive environments? Might they not be the very contexts required for the urgently-needed new myths to develop? What if collective, creative mythmaking offered the means, not just to avoid our modern spiritual desert, but actually to replenish it? What if this task was, collectively, our shared task of tasks?

What if re-enchanting the world were the great endeavor of our generation? What if transforming God into a new form was the cathedral for our children’s?

Here I would like to explore these bold possibilities by traversing the full range of personal myth—to hoist sail and embark out into its still-unnavigated waters: expanding the map of personal mythmaking even further, to reveal not just what it is, but—more importantly—what it could be. Here I will explore how the meaning from personal mythmaking can extend beyond the individual to create a vast, collective web of inter-personal significance—even to the point of forming a shared, cultural project: the kind of aspirational effort that founds and motivates whole civilizations.

Beginning with more typical personal myth work (focusing first on the psychological function, then integrating the metaphysical function), we’ll see how personal mythmaking can bring a transformative sense of meaning back into modern individual lives. From there, we’ll move on, to see how these efforts develop into another level—what I call “creative spirituality”—wherein mythmaking is re-integrated into the communal sphere to address once more our connection to the universe (the cosmological function) and to each other (the sociological function). Here, a culture of personal mythmaking blends into a new cultural myth—the New Myth some have seen on the horizon, but as yet failed to approach.

A new mythology is waiting to be born, a communal project like never before, in which every individual can take part.

It all begins with us.

NEXT: 2. DRAFTING

Print copies available here:

NOTES

[i] Joseph Campbell (1968) Creative Mythology (Penguin, New York), 5; emphasis added.

[ii] Carl Jung (1961) Memories, Dreams, and Reflections (Vintage Books, New York), 171; emphasis added.

[iii] It should be noted that, to call Memories, Dreams, Reflections a “memoir” is not, strictly speaking, accurate, since large portions were largely ghost-written or otherwise heavily redacted by hands other than Jung’s. Nevertheless, it still serves more or less as Jung’s “authorized autobiography.”

[iv] Carl Jung (1956), Symbols of Transformation (Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ), xxiv-xxv.

[v] Memories, Dreams, Reflections, 173.

[vi] Ibid., 174.

[vii] Ibid., 174.

[viii] Ibid., 174.

[ix] Ibid., 174.

[x] Ibid., 188.

[xi] Ibid., 185.

[xii] Ibid., 223.

[xiii] Ibid., 225.

[xiv] Ibid., 225.

[xv] Stephen Larsen (1990) The Mythic Imagination: The Quest for Meaning through Personal Mythology (Inner Traditions, Rochester, VT), 15.

[xvi] Creative Mythology, 93; emphasis original.

[xvii] Dan P. McAdams (1993) The Stories We Live By: Personal Myths and the Making of the Self (The Guilford Press, New York), 34.

[xviii] David Feinstein, Stanley Krippner (2008) Personal Mythology: Using Ritual, Dreams, and Imagination to Discover Your Inner Story (Energy Psychology Press, Santa Rosa, CA), 6.

[xix] Adapted from Creative Mythology, 4-6, 621-24; Pathways to Bliss (New World Library, Novato, CA), 105-107; and Lectures: “The Inward Journey,” “The Thresholds of Mythology,” “Oriental Mythology, “Confrontation of East and West in Religion,” and “Mythology in the Modern Age.”