Building the Cathedral | 4. Materials

Working with Experience and Archetypes

THE HUMBLE HOLY

But…the holy? Where does one even begin?

As before, the answers must come, ultimately, from yourself, your own experience.

Sam Keen, a popularizer of the concept of personal myth in the late 20th century and someone who worked with Joseph Campbell on the topic, expressed this idea succinctly. “If I am to discover the holy,” he wrote,

it must be in my biography and not in the history of Israel. If there is a principle which gives unity and meaning to history it must be something I touch, feel, and experience. Our starting point must be radical. …Is there anything on the native ground of my own experience—my biography, my history—which testifies to the reality of the holy?[i]

Finding the holy or sacred in your life doesn’t necessarily mean you have to have some transcendent mystical experience or daily communion with spirits. Start small. Remember: our disenchanted modern world has become so alienated from any sense of the numinous that it can feel like working an atrophied muscle. All that you’ve done so far to develop your mythopoeic imagination, though, has put you on your way. Through cultivating a “symbolic consciousness” and learning to keep the objective and the imaginative worlds in proper conversation, you are now much better tuned to, in the words of the poet A. R. Ammons, “consider the radiance” of the world as it is.

In A Religion of One’s Own: A Guide to Creating a Personal Spirituality in a Secular World, Thomas Moore proposes some modest ideas for fostering your own personally-attuned sense of the sacred. “In developing a religion of one’s own,” he writes,

it’s important to cultivate an eye for the numinous, a sacred light within things or an aura around them, the feeling that there is more to the world than what meets the eye. You don’t have to be naïve or literal about this; it’s simply a capacity in human beings to catch a glimpse of the infinite in the finite world, or deep vitality and meaning in what would otherwise be hollow and only material.[ii]

You’ve already practiced this sort of sensibility in relation to your biographical history. It is the imaginal art of seeing more than accident in what occurs, something more intentional, significant, a deeper purpose.

As with your biography, this does not mean becoming “naïve” about objective reality. Nor does it entail white-washing away the hardship and apparent negativity of life. Rather, it means decidedly embracing existence, including the darkness, as meaning-full—part-and-parcel of the same great power unfolding in all that is.

When you consider the radiance of the whole of existence with such a pair of eyes, writes Ammons,

then

the heart moves roomier, the man stands and looks about, the

leaf does not increase itself above the grass, and the dark

work of the deepest cells is of a tune with May bushes

and fear lit by the breadth of such calmly turns to praise.

A personal articulation of this power—this mysterium at the heart of being, which has held your greatest, most sublime moments and also, as Ammons says, floods the bones of birds, looks into the guiltiest swervings of the heart, and illuminates the bodies of the flies that feast on shit and carrion—such an articulation must eventually become the task of personal mythmaking.

For many, this radiance shines through in those great transitional moments: births and deaths, each one bounded by the transcendent. Or perhaps other pivotal events have been similar: the day you met or married your partner, had some transformative spiritual insight, acquired a life-changing injury, or found some meaningful forgiveness or redemption. Otherwise, less profound but still significant events can shine with the numinous: synchronicities, welcome breakthroughs, or an unexpected and seemingly impossible serenity amidst a tumultuous time.

SALVAGE AND RECLAIM

According to Jung and Campbell, an intuitive sense of the numinous is instinctual in every human being. All it needs is the proper stimulus to become activated. Certain settings and images work in just this way to evoke the sense of the numinous—we only need to open ourselves to them.

Jung famously called these psychological instincts the archetypes of the unconscious—essentially, patterned responses lying latent within us, which are triggered by engagement with associated forms. Such was the function that mythological symbols and rituals served in the past. And, though no longer operative as part of a comprehensive tradition, they can still function to varying degrees today, and thereby serve as guides. The development of a personal sense of the sacred and numinous does not mean that such traditional mythic forms are irrelevant, that they should play no part or that tradition should be ignored or rejected. Rather, we must learn to use what we have as best we can.

As T. S. Eliot wrote in the early 20th century, we live in a waste land littered by “a heap of broken images.” It has become virtually impossible now to inhabit a comprehensive mythic cosmos as humans once did. What we can do, however, is look through the heap of images history has left us in an attempt to build anew. While these mythologies no longer function as complete and effective mythic systems, their images and symbols can still speak to us as helpful aids: breadcrumbs, you might say, to a working personal expression of the divine. Engaging with them can still stir the archetypal patterns lying latent within, and help awaken your dormant sense of the numinous.

Imagine entering the ruins of a temple from a long-lost civilization. You walk around the courtyard of tumbled pillars covered in ivy. In the bas reliefs carved there, you can make out scenes of gods and goddesses. You don’t know their names or their stories, the full dynamics of their sacred epic, but you feel stirred, somehow, nonetheless…

You walk up the stairs and enter a small enclosure. Somehow, you know, this was the inner sanctum, the holy of holies. You feel a shudder, a significance, a solemnity, though you don’t know why or what of. On the ground lie a broken chalice and some strange figurines. You pick them up and hold them in your hand. You can never know how these were once used, what ritual they spoke to, how they integrated all the pieces of a robust cultural myth into a powerful Story, but you find them infinitely compelling nonetheless. Clearly, the artisan who worked them succeeded in capturing something powerful. The myth is gone, but the symbols still speak, if only faintly, yet still movingly…

Historically, it has been the case that new temples were built on the sites of the old. New gods, even whole new religions may come through—but the sacred site remains. Such things are still powerful, even when the specific Story behind them has been stripped away. The place is rededicated; a pagan temple becomes a church becomes a mosque. But something is preserved—the inherent numinous character. Symbols are reinterpreted, if only so their evocative nature can continue to work in a new context.

So is it for us today. The Old Myths are dimming, their Stories no longer working to cohere a livable mythic narrative we can inhabit. But their many pieces persist—vestiges of numinous encounters, relics of engagements with the unconscious.

As Campbell sees it, a sensitive engagement with such materials is the best method one can use to discover and develop your own personal myth. He writes:

The way to find your own myth is to determine those traditional symbols that speak to you and use them, you might say, as bases for meditation. Let them work on you. …Let them play on the imagination, activating it. By bringing your own imagination into play in relation to these symbols, you will be experiencing…the symbols’ power to open a path to the heart of mysteries.[iii]

What mythic symbols speak to you?

Perhaps it’s the mandala.

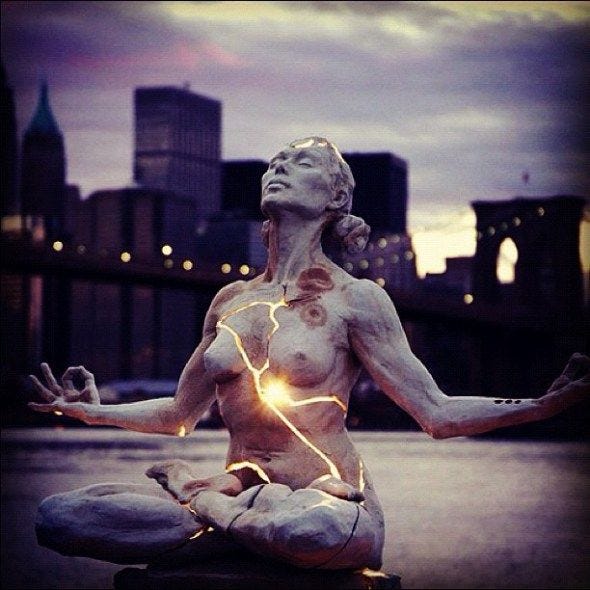

The Earth Goddess.

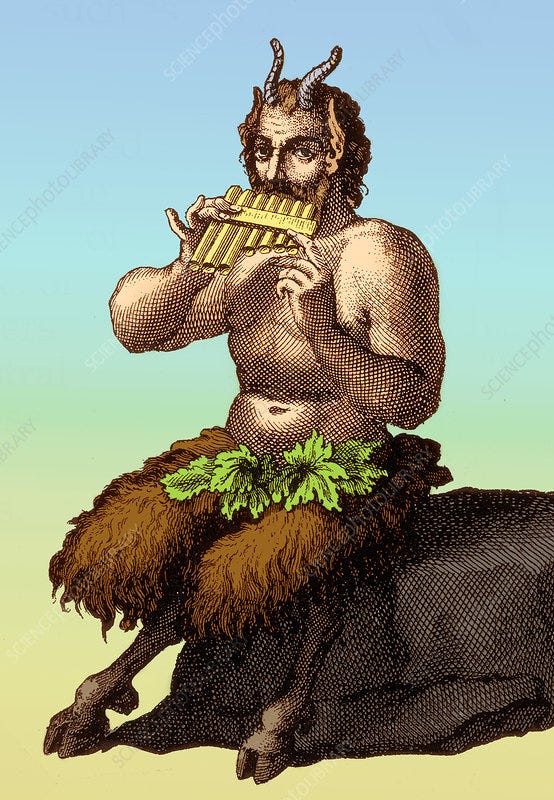

The rustic Pan.

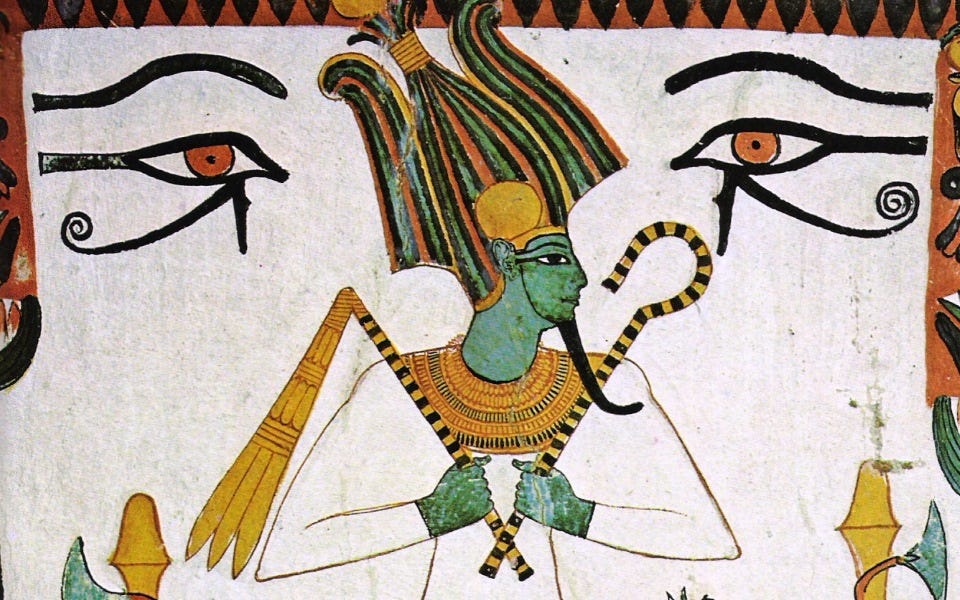

The dying-and-rising god.

The nine orders of the angelic hierarchy.

The paradisal garden.

The dragon-slayer.

The divine man.

Whatever draws you, meditate on such images…

Allow your mind to play with them.

Imagine new configurations and associations.

Let the divine players dance…

Of course, traditional religions are more than just systems of mythic symbols. They contain a plethora of materials, such as ethical teachings, life wisdom, mental and bodily practices, distinct artforms, and communal rituals. All of these can be the source of inspiration and an evocation of the numinous sensibility in you. Moore reflects:

When you decide to create your own religion, you will want to study the traditions of the formal religions with a fervor you’ve never known before. You’ll discover how valuable they are and how much beauty and wisdom lie in their art and texts and stories and rituals and holy images. You’ll want to learn from Buddhist sutras and the Gospel teachings and the Sufi poets and the sayings of Lao Tzu and Chuang Tzu. You will be amazed at the beautiful precision of the Kabbalah and the acute spiritual sensitivity of the Qur’ān—all because you know what it’s like to search for spiritual insight and express your spiritual feelings.[iv]

For most people who live their lives within a particular religious tradition—Christianity, Buddhism, Islam, etc.—there is no choice here. They must accept what their tradition has given them—and reject other traditions. The canon is set, the dogma is handed down. One can either take it or leave it.

Crucially, this is not the case for someone developing a personal mythology. Unlike those who practice within such traditional religions, you are not bound to any one of them or even any element therein. You are free to play the curator—to listen to your heart and see what genuinely speaks to it. From this you craft your vision. Take what works; leave what doesn’t. “It makes a big difference,” writes Moore,

whether you feel free to borrow this wisdom or feel you have to buy into it. …Don’t take the traditions as they’re offered. Struggle with them, work hard at extracting only what is valuable in them, and be ready to discard the dross.[v]

Perhaps a moral saying in one of the Gospels strikes a chord: “Judge not, lest ye be judged.” This moves you, resonates as profound and speaks to a truth at your core. Take it into your myth. Conversely, “whoever marries a divorced woman commits adultery” lands with a thud. Leave it. Your heart will tell you the path to take toward the sacred. Conscience, not dogmatic orthodoxy, is your criterion; beauty, not canonical status, is your guide. Campbell writes:

an intelligent “making use” not of one mythology only but of all the dead and set-fast symbologies of the past, will enable the individual to anticipate and activate in himself the centers of his own creative imagination, out of which his own myth and life-building “Yes because” may then unfold. But in the end, as in the case of Parzival, the guide within will be his own noble heart alone, and the guide without, the image of beauty, the radiance of divinity, that awakes in his heart amor: the deepest, inmost seed of his nature, consubstantial with the process of the All…[vi]

Let the calling of your subjective imagination lead you.

At the same time, don’t let it entirely dictate the show either. Listen also to objective insight as well. Unlike mythologies of the past, yours is being made wittingly, in the full sun of conscious awareness. This, too, can be a tool. Follow your heart, but accept input from your mind as well—as all good play allows. Note that an archetypal symbol might resonate with you, but also weigh critically the implications of following it. Not all archetypes, when activated, trigger a divine calm or compassion, a healthy Yes or a sacred ecstasy. And while it is important not to shun the darkness, it is also not ideal to “give the devil a foothold.” As Jung noted in The Archetypes of the Collective Unconscious, powerful and destructive ideologies such as Nazism, too, activated deep archetypal forces. A psychology plagued by pathological shame might resonate powerfully with the “Fall of Man” trope; a narcissist, perhaps, with Promethean hubris. So be careful. Probate spiritus (“test the spirits”), as Jung was fond of quoting. Developing personal myth requires the application of conscious decision-making as well as the tug of fantasy.

Daniele Bolelli is a writer whose works include a cheeky but often earnest and insightful book called Create Your Own Religion. In describing the process of doing just that, Bolelli writes:

We can observe the historical consequences of certain beliefs, and decide which ones have had more desirable effects on our lives. …In creating our own religions, we should carefully separate those ideas that have contributed to the amount of violence, conflict, and suffering in the world from those that have helped alleviate or diminish those things.[vii]

This seems like sound advice, and a natural consequence of conscious mythmaking. Indeed, we find ourselves at a unique stage in human history, when the development of myth has entered a phase wherein the least developed elements of the human psyche need no longer find unquestioning acceptance simply because of the authority of tradition. Put rather simplistically, traditional myth had offered meaning, but at the often-destructive expense of critical awareness; modern rationalism has offered the critical awareness to avoid such destructive behavior, but often at the expense of meaning. Conscious mythmaking takes the best of both, with the potential to offer both meaning and a constructive orientation to life.

OLD WINE SKINS

Working with mythic symbols can be a good way to connect the conscious and unconscious worlds and open your imagination for numinous experience. In this way, symbols act as mediators between you and the numinosum. They are a bridge, a conduit, a translation between it and you. However, there are also categories of experience where the connection is more immediate and direct. Bond calls such high-intensity ruptures “core experiences,” and these can become the grain of sand around which the pearl of your personal myth grows. It can be very helpful to have the traditional symbols to look to after such experiences. Often, they can play the mediators in the other direction—not in translating the numinous to you through culture, but in translating the numinous back to the culture through you.

Say one has an ineffable numinous experience. The usual way such an experience gets communicated, if it does at all, is by translating it into the given religious or mythic language of one’s culture. This is a big part of the reason why Christians who have visionary experiences express those visions as being of Christ; Buddhists, of Buddha, etc. The culture provides the framework and the symbols by means of which numinous experiences can be meaningfully integrated into the world.

However, much is always lost in translation. A given language imposes its own limits, and sometimes the cultural framework available is not really adequate to the task of communicating a personal core experience. For instance, Bond relates the story of a woman whose core experience involved a profound early-morning encounter with crows, for whom she felt compelled to dance, and by whom she was then led to a mighty oak tree. The experience was personal and profound—but attempting to integrate its religious quality into her life and culture poses a challenge. Was this a “Christian” experience? A “Native” one? What happens if no preexisting label properly applies? What if there is simply no way to “convert” the experience into pre-given forms? “The claim of the crows on this woman,” writes Bond,

has the beginnings of a personal religion. To make a statement, even to herself, about what happened to her, she has to put it in a framework. She needs the frame that tells her how to relate to this experience, that is to say she needs a religious myth to guide her in the relationship to her living psyche. Dancing for the crows was a religious experience, a numinous experience. It forms a core experience. …She may attempt to put it in a cultural religious frame. This woman, for instance, may embrace Native American mythology rather than having to labor over a personal myth. Often nowadays people turn to religious forms and practices outside of their own culture. We do not know if such a “conversion” will be adequate to the claim. The difficulty with conversion has to do with the restless urge of psyche to know itself ever more fully. Where the potential of the individual relationship to psyche exceeds the potential of the culture—any culture, ancient or living—the ground is set for the individuation process to unfold.[viii]

In short, our core experiences of the numinous may not “fit” with any given symbol or system. To attempt to force them to does violence to the very thing that makes it what it is, what makes it special. In this way, cultural myths and religions often act as a Procrustean Bed for our own numinous experiences. It is new wine in old wine skins; trying to mix them may cause both to be ruined.

In such instances, rather than force the fit, we should learn instead to speak our own novel mythic language. To do so, we will need to move beyond tradition, having by now hopefully integrated the insights of its rich treasuries of myths and symbols into our imagination for inspiration. Now, we will need to do something even more challenging than building anew out of the old.

Now, we will need to create mythic imagery.

Larsen writes:

It is an open question…whether the true meaning of personal mythology is simply to discover that we are repeating a traditional mythic pattern or, as Yeats suggested, that we are in touch with a still-alive “supernatural,” which requires us to create new mythologies with the very stuff of our lives. If we are searching for patterns, we must rely on our reading of myths. If we must create new myths to live by, however, knowing traditional myths may be helpful but not enough. What new thing may be required of us is as yet unknown; but we may find that the answer lies only in the living.[ix]

Here the road diverges somewhat. The aim to “create new myths to live by”—what Joseph Campbell called “creative mythology”—is not for everyone, but rather is to be pursued by “an adequate individual, loyal to his own experience of value.”[x] Instead of mining the past for materials, these mythmakers must forge entirely new bricks out of their own imaginations, intuitions, and experiences if they are to build their cathedral. In so doing, they may just offer something for all of us.

NEXT: 5. CONSTRUCTION

Get a print copy here:

NOTES

[i] Sam Keen (1990) To A Dancing God (HarperCollins, New York), 99.

[ii] Thomas Moore (2014) A Religion of One’s Own: A Guide to Creating a Personal Spirituality in a Secular World (Gotham Books, New York), 4.

[iii] Campbell, Pathways to Bliss, 97.

[iv] A Religion of One’s Own, 8.

[v] A Religion of One’s Own, 28, 31.

[vi] Campbell, Creative Mythology, 677-78.

[vii] Daniele Bolelli (2013) Create Your Own Religion: A How-To Book without Directions (Disinformation Books, San Francisco), 33.

[viii] Bond, Living Myth, 70-71.

[ix] Larsen, The Mythic Imagination, 11.

[x] Campbell, Creative Mythology, 7.