What Is Metamodernism?

A Beginner's Guide to Going Meta

Beyond Postmodernism

For those paying attention, it is obvious that the cultural vanguard has long since moved on from the played-out tropes and predictable strategies of “postmodernism.” That story is old, and there is, by now, over a decade’s worth of academic literature devoted not just to postmodernism’s decline but to what has arisen to succeed it since the early 2000s. While the legacy of postmodernism will of course live on and continue to permeate society, it is hardly the spearpoint anymore of cultural innovation. Something new is afoot in areas where postmodern forms recently held court. Apparently, the consensus that has emerged among cultural theorists, art critics, sociologists, philosophers, and other social scientists is that this new paradigm bears the label “metamodernism”—a term which, despite its downsides, is certainly an improvement over the provisional stand-in of “post-postmodernism.”

But just what, specifically, characterizes this metamodern turn in culture? And why does the prefix “meta” seem to have found such broad appeal—or, actually, more than that: independent convergence? For, in the short span between 2017 and 2021, for instance, no less than four different books were published by different authors of different backgrounds attempting to describe a “metamodern” successor to the postmodern throne. These included:

2017’s Metamodernism: Historicity, Affect and Depth after Postmodernism, an anthology of essays edited by cultural theorists Timotheus Vermeulen, Robin van den Akker, and Alison Gibbons;[i]

2017’s The Listening Society, Volume 1 of the Metamodern Guide to Politics Series by sociologist and philosopher Hanzi Freinacht;[ii]

2019’s Metamodernity: Meaning and Hope in a Complex World by author, educational philosopher, and futurist Lene Rachel Andersen;[iii]

and 2021’s Metamodernism: The Future of Theory by philosopher and historian Jason Ānanda Josephson Storm.[iv]

Some of these authors were drawing upon and extending the term’s use by others, while some came to it independently. We may thus rightly ask: What are these metamodernisms? Is there anything more than shared terminology linking these articulations of what comes after postmodernism? Or is the apparent consensus on a label little more than a superficial similarity masking a deeper theoretical incoherence?

As we shall see, there are without doubt meaningful distinctions in how the above writers have understood and applied the term. There are cultural theorists (like Vermeulen and van den Akker) who use metamodernism to speak primarily of developments in art and culture, for whom the label marks a distinct cultural period and “structure of feeling” (à la Raymond Williams). Some of them (Linda Ceriello and Greg Dember) also refer to it as an “episteme,” or structure of knowing (à la Foucault). On the other hand, other thinkers (like Freinacht and Andersen) speak of metamodernism as a stage in culture’s continual “complexification” of symbolic “codes,” including postmodern insights while also transcending beyond them. Still others (like Storm) are proposing metamodernism as a new philosophical “paradigm” that offers new avenues for thought and research beyond the old deconstructive methods now reaping diminishing returns in academia. Within this milieu, various thinkers have adopted the term to identify developments in scientific thought and even religious/theological reformulations.

Given the diverse domains from which these theorists and adopters of “the metamodern” have arisen, and the consequent difference in emphases and areas of focus, it is understandable why some might presume their theories to have little in common.

They would be wrong.

With this book, I hope to add yet another theory of metamodernism to the mix—not to further muddy the waters but, in fact, to better clarify what metamodernism is by showing how all of the above are part of the same pattern emerging in cultural consciousness. That is, I would like to offer a new and unique theory of metamodernism, but one that can also act as a synthesis of its prior articulations. This new theory of the metamodern will have greater explanatory power, revealing new levels of relationality that allow us to track metamodern developments in the arts, philosophy, science, religion, and beyond. And it will accomplish all this by means of an integrative analysis that synthesizes the insights from each of the preexisting frameworks, showing every one to hold a true yet partial, correct but limited, perspective on the metamodern perspective.

So, what is metamodernism? To see this, we’ll need to appreciate just what it really means to “go meta.”

Eternal Recursion and Infinitesimal Progress

All forms of the “metamodern” get their name by affixing the Greek prefix meta- to “modern” in the same way that its predecessor was delimited by adding post-. The meaning of post-modern is relatively straightforward: essentially, “that which comes after and critiques the modern.” The prefix meta, however, is a bit more ambiguous given the different meanings it can have in the original Greek. Meta can mean “with,” “between,” or “after/beyond,” as well as some other prepositional relationships, depending on the case used for the noun it modifies. (I’ll spare you the grammatical details—despite the rare opportunity it affords me to actually make use of my defunct Classics degree). This is significant because, as we’ll see, the different theories of metamodernism all lean on these different potential meanings in their justification for employing the term. Here I would like to make my own case for putting the “meta “in metamodern, and in the process mark out my own theory relative to this usage.

The meaning of meta I wish to highlight is not purely etymological, but actually draws on a concept that arose through an intriguing historical accident. The concept I am referring to is the “meta” of reflexive abstraction. Despite the ten-dollar term reflexive abstraction, this phenomenon should actually be rather familiar to you as it has recently come into fairly popular usage (not an incidental fact in a metamodern culture!). To call something “meta” or (usually half-ironically) “so meta” means that it is somehow engaged in a self-reflective loop: say, a song about songs, a play about plays, or a film about films. When a writer writes about writing (as in Still Life with Woodpecker, wherein the author repeatedly offers tangential interludes about the typewriter he is using to compose the book you are reading) or a television show depicts itself (as in the episode of Boy Meets World in which a character goes to Hollywood to play his own role in a show called Kid Gets Acquainted with the Universe), they are “going meta.” That is, they are nesting a representation of themselves within yet another, higher-level representation. They are recursively reflecting on themselves, creating levels within levels—a bit like a funhouse mirror.

The historical accident from which this use of “meta” derives is actually the (mis)understanding of the meaning of Aristotle’s Metaphysics. In the ancient ordering of Aristotle’s works, his work on nature, Physics (Physikē), came first, after which came the stuff (very appropriately titled) After Physics (Ta Meta Ta Physika). The latter dealt with philosophical abstractions like the nature of causality, matter, God, etc. The implication that people drew from this was that there was, well, physics (about matter and stuff) and metaphysics (about the stuff beyond matter and stuff). Through this rather stupid historical confusion about some pretty intellectual things we get not only the field of “metaphysics,” which today refers to any kind of higher order philosophical reflections on what makes the physical world possible, but also the derivative concept of “meta” as the higher, broader take on a topic; meta as the transcendent concept per se.

Once you know the rule you can play the game: it can get you metapsychology, metamathematics—you name it. So, from this back-formation, Merriam-Webster defines “meta” as that which is “more comprehensive: transcending,” specifying that it is “usually used with the name of a discipline to designate a new but related discipline designed to deal critically with the original one.”[v] So Wiktionary offers for “meta”:

Transcending, encompassing.

Pertaining to a level above or beyond; reflexive or recursive; about itself or about other things of the same type. For example, metadata is data that describes data, metalanguage is language that describes language, etc. [From 17th century][vi]

It is in this sense that I will theorize about the metamodern turn in culture after postmodernism, according to which meta suggests, essentially, recursive transcendence through iterative self-reflection.[vii] Simply put, going meta on something means creating a new level of analysis that can deal critically with it from a more transcending, encompassing vantage.

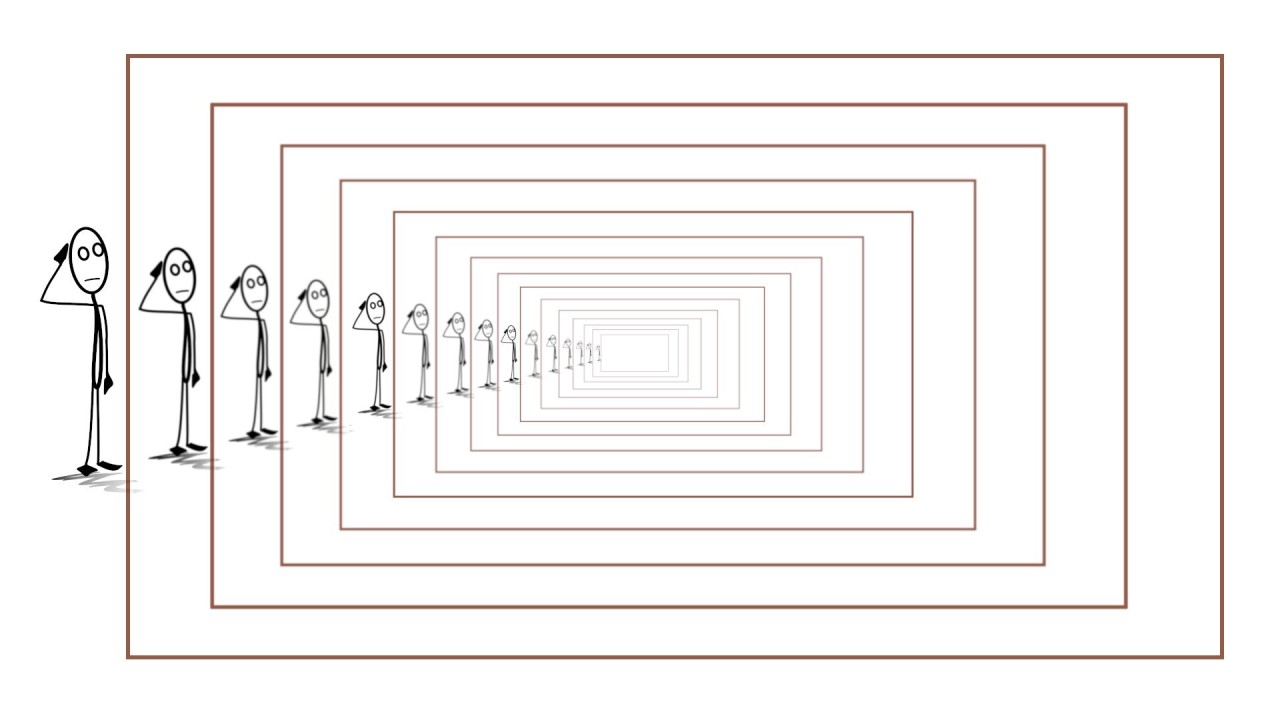

This kind of meta follows an identifiable logic. The basic move occurs through a process we can call decentration, whereby a given perspective becomes the object of analysis to an even higher-level perspective. To picture this, imagine a circle representing all the contents of a given field of awareness relative to a single, central perspective. From one’s position in the center one can look around and see any objects that fill one’s horizon from that position—everything bounded within one’s “circle of awareness”:

Now imagine stepping outside this bounded circle of awareness to a new vantage and, from there, obtaining an even wider scope. In doing so, one’s center has shifted—one has decentered oneself from the earlier perspective—and from this position the old, smaller scope now exists within the wider one as an object in one’s field:

From this broader, higher-level perspective, one can “look down” and reflect upon one’s old perspective. Its limits are now clear, and the entire horizon of the old view now lies within the expanded horizon of the new. A smaller “copy” of one’s old self now exists within the larger whole—a previous perspective residually residing in the new one like a miniscule reflection: a representation of one’s older approach to representation.

Now imagine this process repeating, over and over, iterating on itself again and again, until there are circles within circles within circles through an endless decentration to higher and higher vantages. This is what it means to really “go meta.”

This process is inherently an evaluative, critical one since, as reflection upon the lower-level perspective is compared to the wider scope of the new perspective, it is found wanting. It is now clear how much of the “bigger picture” was missing from the old view of things. Because of this, going meta comes with critique. The new perspective sees things the old one could not and is thus newly aware of its deficiencies.

However, as the process iterates, even the wider perspective reveals its inadequacies compared to a still larger ken, and so on. Because each new iteration of recursive reflection represents an advance towards a greater, more comprehensive vision of the totality, it marks a genuine transcendence to a new order of insight and awareness. Knowledge is gained and more of provisional reality is revealed.

Such is the nature of recursive transcendence through iterative self-reflection.

So, what am I saying? The claim I’d like to make is that cultural shifts—like those from modernism to postmodernism to metamodernism—reflect society-level manifestations of such recursive, self-reflective moves. Postmodernists come after, objectify, reflect upon, critique, and transcend modernism; metamodernists come after, objectify, reflect upon, critique, and transcend postmodernism; and so on. As they do, genuinely novel insights and sensibilities are generated that justify speaking in terms of distinct cultural phases.

This novelty is the litmus test for assessing a true advance instead of simply some lateral change. That is, recursive self-reflection has a direction. It moves necessarily towards wider, more encompassing perspectives and away from smaller, more parochial ones. Because of this, we see that all formulations of the metamodern have in common an attempt to move beyond postmodernism yet by means of postmodernism.

Any articulation of metamodernism that does not include postmodern insights is not actually metamodern, since it shows no sign of being post-postmodern. For instance, a critique of postmodernism based on supposed deviations from injunctions in inerrant scripture will almost certainly not be a metamodern critique but only a reactionary, traditionalist one. Similarly, any critique of postmodernism based on its rejection of a technological utopia attained by acquiring ultimate knowledge will almost certainly be but a reactionary, modernist plea. Neither actually grapple with the genuine insights of postmodernism, so neither can claim to have surpassed it. By contrast, a critique of postmodernism based on applying a deep understanding of its own critical principles to itself in a manner that produces novel ideas and directions—that would indeed be a metamodern move, since it evinces the ability to master and move beyond that which it critiques. By the nature of its critique, it reveals that it does indeed possess a higher vantage and so marks an advance beyond postmodernism (metamodernism) and not simply a move back or away from it (various lower forms of anti-postmodernism).

In this way, recursive reflection has directionality. Going meta never means diminishing one’s scope of perspectives, but always increasing it. By definition, it is what allows one to step outside a given frame to see more of the picture. It’s like a person in a painting climbing out of the painting and then looking back at where they had been encased. Now they can see the whole context of their former position: it was just a painting! They can also see their old context within the broader context of their new vantage: an art gallery! They can see more of the relationships that hold in this context. They see, for instance, that their old context was just a painting, and not the fullness of reality. Except, the process is iterative, so before long it becomes clear that the “reality” in which they currently stand is also limited. Transcending again, imagine the person now climbs out of a television, and can see that the art gallery was itself just in their TV as the painting was in the art gallery! The TV contains the gallery and the painting, but the painting does not contain the gallery or the TV. The context of the TV “contains more” than the context of the painting, allowing one a broader view of (provisional) reality.[viii]

In short, higher vantages provide more information than lower ones. There is more to reflect on, and so more to inform one’s thoughts and actions and feelings. One might compare this to increasing the resolution of one’s screen. “Upgrading” to more reflective perspectives takes you from a screen of a few pixels hard to decipher to the quaint resolution of an 8 bit computer game all the way to a 4K high-definition TV. Higher and higher resolutions bring more and more information, and show more and more of the picture, making more of the context clearer. Or, even better, one might compare perspectival shifts in terms of gains in dimension, like the one you experience when you upgrade from a 2D film to a 3D one. Now you can see the objects in a higher dimensional plane.

Indeed, the geometric logic of increasing dimensions is very much the same as iterative recursive reflection. At each level, the unit of the last level is placed in a higher-order organizational context through an “orthogonal move” to a new vantage—just like decentration. Decentering from the 0D point to a position beyond it establishes a new dimension: the 1D line, made up of points. Decentering from the one-dimensional line to a position beyond it establishes the 2D plane, made up of lines, and so on. In the process, qualitatively new sets of relations are created. The pluralization of the unit allows for the plurality to be related, linked, connected, defining the parameters of a whole new dimension. New relations mean new kinds of information in richer, more complex forms that contain their earlier, less complex forms: cubes contain planes which contain lines which contain points, etc. The process is iterative and endless, as every new dimension can become the unit in a yet higher n-dimensional space.

The fact that such higher vantages contain more information makes them more complex. Complexity refers to the number of integrated parts a thing has. Once a perspective becomes a decentered object of awareness, it becomes but a part in a bigger whole. As a part, its relationship to other parts (i.e., perspectives) can be assessed. More perspectival parts integrated in more contextual webs of relation mark an increase in perspectival complexity.

This follows directly from all that we have been saying, yet it leads us to an interesting (and perhaps, for some, startling) conclusion: cultural shifts—like the ones from modernism to postmodernism to metamodernism—are movements of complexification. Metamodernism is not just temporally after (“meta”) postmodernism; it is beyond (“meta”) it. Metamodernism is a more complex perspective than postmodernism, which was itself a more complex perspective than modernism. Such cultural shifts are not just changes, they are developments. Postmodernism saw more of the picture than the modernists (e.g., that minorities were marginalized by its grand narrative; that technological progress also posed systemic existential risks; that a single, final Absolute Truth cannot be attained, etc.). Now, metamodernists see more of the picture than postmodernists (e.g., that grand narratives can be reconstructed according to infinite deconstruction through eternal recursive reflection and critique, and that this itself provides the logic of meaning and value, etc.).

Specifically, metamodernists see not just that different cultural logics are at play in the world (this was the insight of the postmodernists); no, metamodernists see (to varying degrees) the logic behind these different cultural logics, the pattern that gives rise to the recognizable typology of different perspectives. What logic is that? The very one I have been outlining here: an algorithmic process of recursive self-reflection, by means of which cultural logics become aware of one another, of themselves, and of the very process that generates them.

But, before metamodernists go getting too big for their britches, it should be clear: the process keeps going! The metamodern perspective is also just another center of perception that one can in turn decenter from to see a wider context. Just what that looks like will only become clear in time—as metamodernism is itself objectified, reflected upon, critiqued, and transcended. But, if metamodernism does indeed reflect something real, then this is unavoidable. In this way, metamodernism presumes its own transcendence. It embraces its own inevitable obsolescence. In doing so, it escapes the triumphalist modernist illusion of ever attaining any sort of final telos or end. Its telos is a receding telos, its end is an endlessly iterating self-recursion and self-transcendence.

This is a key idea, so let’s give it a name. Friedrich Nietzsche spoke of “eternal recurrence” as the core idea grounding his radically immanent philosophy. As a nod to him (while seeking to move ahead), I will suggest eternal recursion as the grounding idea of this immanently-transcendent perspective. This eternal recursion is progressive, since it is continually reaching more comprehensive perspectives. At the same time, this progress is paradoxical, since how can one make any progress in an infinite process? The advance is towards a continually receding horizon. There is no final Absolute, rendering all gains relative; and yet, in their relativity to one another, their gains are absolute.

This sort of paradoxical advance I call infinitesimal progress (movement by means of infinitely diminishing strides) or, more grandiosely, zenonian progress after the Greek philosopher Zeno and his paradoxes of motion. How does one reach a destination when the ground one must cover is recursively divisible into smaller and smaller parts? The metamodernist, appeasing both modernists and postmodernists, assures: “All progress is relative.” Progress is real, but it lies in the going. In the words of Emily Dickinson: “So instead of getting to Heaven, at last – / I’m going, all along.”[ix]

Epistemic Bootstrapping and Perspective Toggling

In retrospect, eternal recursion has always been the means by which transformations of cultural logics have occurred throughout history. Through people’s continual reflection, culture has been building on itself, each new level of reflection becoming the basis for the next. This is the reflective bootstrapping that has led to successive updates to humans’ collective model of the world. Such “bootstrapping” gets its name from the old adage about “pulling yourself up by your bootstraps.” It refers to the way a thing gets from a rudimentary, lowly place to a complex, higher one entirely based on itself. So a computer “boots up” from a simple starting code all the way into an entire operating system. Through iterative self-reflection and accretive recursion, profound transformations are possible.

Epistemic bootstrapping refers to the way human knowledge has transformed over countless generations of cultural reflection. Through it, not just what we think but how we think has shifted. Reflections build on themselves until they force a total restructuring of knowledge, leading to a punctuated equilibrium of paradigm shifts. These occasional ruptures produce new “epistemes” (as Foucault called them) at higher levels of reflective decentration. So, for instance, after the invention of literacy (which brought language and thought to deeper reflective awareness), we see the emergence of abstract literary philosophy, the rise of science out of natural philosophy, and then the inquiry into the very process of linguistically-mediated knowledge formation itself. Simply told, ancient mythologies yielded to Axial Age thought, which then yielded to modernity—while modernity, of course, yielded before postmodernity, which in turn has recently passed the torch to metamodernity. Each one of these shifts represents a decentration to a higher vantage, a going meta on what had come before:

As this diagram suggests, all the prior epistemes continue to live on within metamodern culture—but are no longer the driving cultural logic. The metamodern perspective thus contains the postmodern, as well as the pre-postmodern, as enduring modalities available to it. Indeed, from its vantage, the metamodern is able to toggle between these different modalities. Like a browser with many tabs, or a hypertext with many links, the metamodern can move through many different windows. Unlike the radical relativism of the postmodernist, though—who gets lost in the plurality—the metamodernist knows their way back to the Home screen that shows the links to all these windows. Different contexts are contextualized.

The metamodern sensibility is thus, by nature, a multi-perspectival one, able to move through the various levels of reflection it contains. So, while the postmodern has foreclosed the possibility of idealism in reaction to the modern, the metamodern can toggle between both, holding modern aspirational enthusiasm one minute, then checking this with a more reflective awareness the next. Crucially, the continual background context that makes this toggling between perspectives possible changes the engagement with each. In this way, metamodernism can engage both the modern and the postmodern modalities and, precisely thereby, be neither the modern nor the postmodern but a higher, third thing that includes yet transcends each.

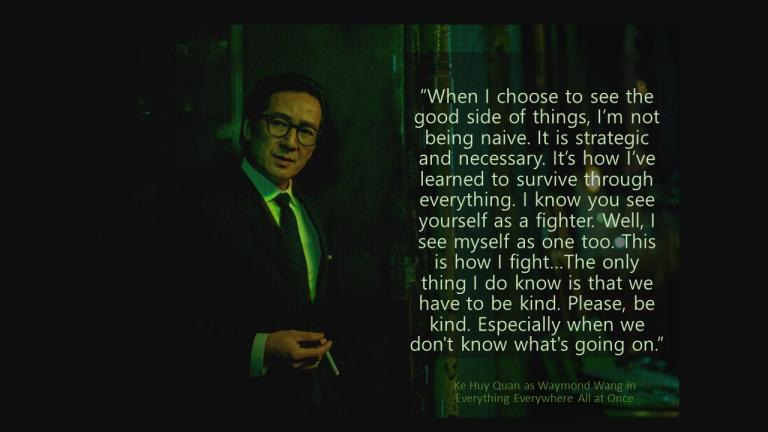

Indeed, the metamodern can, by means of their own reflective self-awareness on their reflectivity, even choose to stop reflecting and simply embrace the immediacy of non-reflection! Through reflection, reflection itself is overcome—a move in some ways comparable to the meditator who can only attain a still mind once they become aware of how restless it has been. In this way, metamodernism opens the possibility of what Kierkegaard called a “second immediacy,” or what Paul Ricœur referred to as a “second naiveté.” This is an immediacy by way of reflection, a naiveté on the other side of being informed. By becoming reflectively aware of the different centers available to one through reflection, one gains the autonomy to choose between them, including abandoning reflexivity entirely. After the obsession with self-reflexivity and the crippling self-consciousness of postmodernism, this can produce an affect of intense relief, as though a liberation or breakthrough has occurred that overcomes the impasse towards unreflective joy and simple being.

As we will see, much metamodern art reflects this reclamation of the simple, the innocent, the sincere and earnest, yet in a manner that reveals it as a product of self-reflection and awareness. Metamodern naiveté is not the same as premodern naiveté. It has passed through modern and postmodern reflections to become aware of reflection itself as a limiting factor. In this way, naiveté is itself transfigured by its history with reflection. Meaning returns as a viable possibility beyond postmodern deconstruction. Yet, because postmodern skepticism remains an open window to which one can always toggle, the dangers of naiveté are mitigated by the broader context of multiple perspectives.

Metamodern meaning entails the mutual integration of different epistemes by finding productive linkages or connections between (meta) them. The modern and the postmodern need not be antagonistic opposites; the metamodern finds a way to relate to both. There is a sensible way to connect these disparate sensemaking modes, a logic to how these cultural logics relate. Metamodernism, you could say, is a cultural logic that can reflect on the cultural logic of cultural logics. It reflexively reflects on its capacity to reflexively reflect on reflection.

Don’t worry, I wrote that last sentence with a devious grin on my face. But why not? There’s no reason we can’t have fun and be serious, self-consciously ironic and earnestly sincere. But before you go and conclude that I’ve simply allowed myself to get swept up in a flight of fancy, that nobody actually thinks this way, that none of this actually pertains to culture on the ground, let’s come back to Earth for a minute—to the work of very serious sociologists. As early as the 1980s, they were recognizing that they could no longer ignore the effect their own theories were having on, well, society. In a cycle very much like the “observer effect” from quantum physics, sociology influences what it seeks to objectively measure. Theories about culture wind up affecting culture. Recognition of this “double hermeneutic” has led to the emergence of so-called “reflexive sociology”: a discipline for sociologists to study the impact of sociology itself on society.

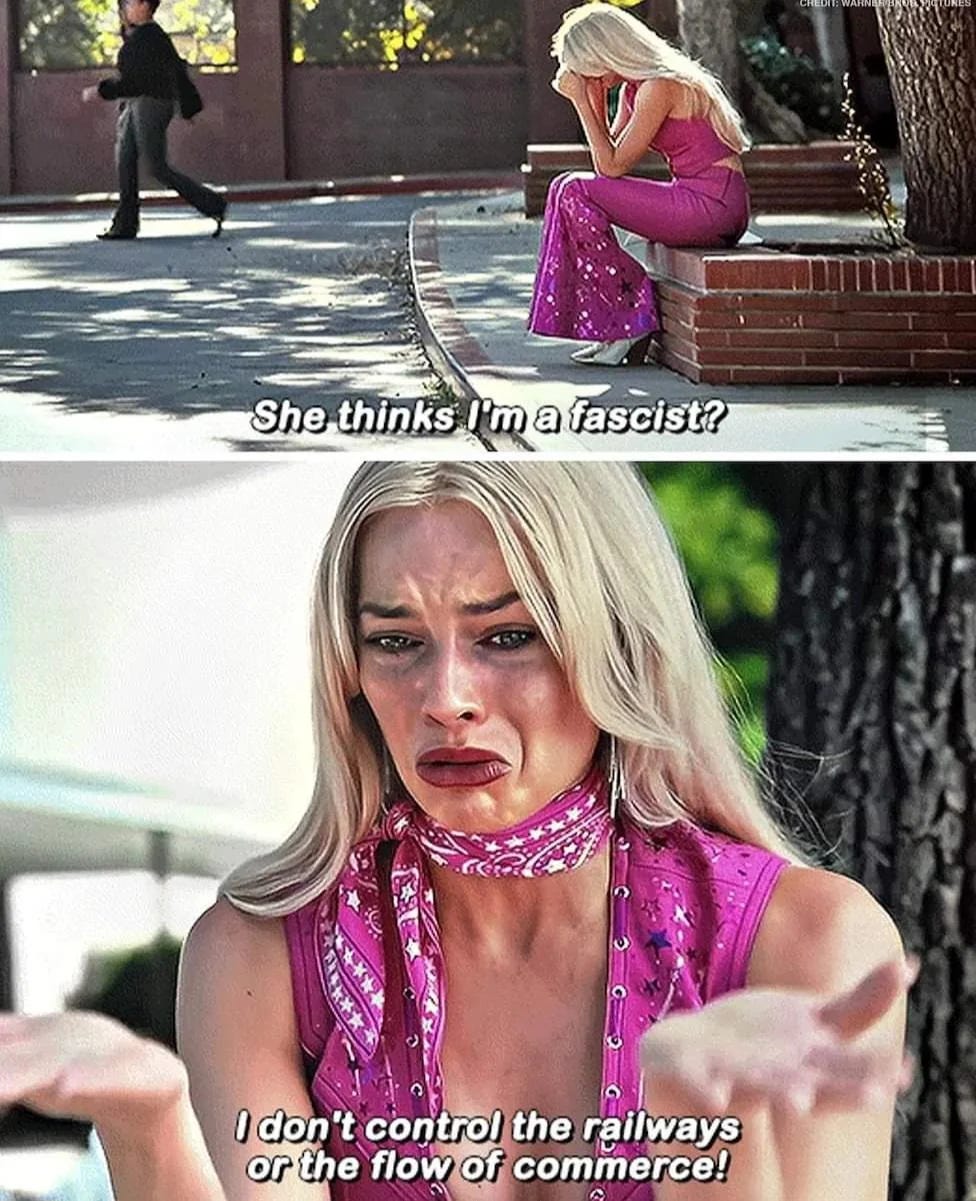

This is not ivory tower abstraction, but very real stuff. Just think about the revolution in gender norms among members of Gen Z. The very language millions of tweens and teenagers are using to formulate their lived sense of identity comes less and less from their immediate familial or community circle and more and more from academic paradigms that critically reflect upon culture. Eleven-year-olds are coming of age using the paradigms of social constructivism. The postmodern deconstruction of culture is increasingly becoming the means of enculturation itself as younger generations are being socialized via sociology. Just consider that the 2023 summer blockbuster Barbie movie wound up being a fun-for-the-whole-family meta-reflection on issues of patriarchy and feminism.

This is simply itself a reflection, not a judgment, and is in no way intended to echo conservative laments about the loss of childish innocence to those “neo-Marxist postmodernists” spreading their “critical theory” in the schools. But the very fact that such popular jeremiads identify postmodernism itself as a boogeyman that everyone has heard of only underscores the point. Cultural theory is not just in the ivory tower but deeply permeates culture itself. But if this level of self-reflexivity is true even of mainstream culture, shouldn’t we expect the vanguard to be that much more self-reflexive still?

The objectification of postmodernism has reached a point where any new self-reflective cultural movement will necessarily relate itself to postmodernism, and to what postmodernism is supposedly about. The future of culture must necessarily pass through its own reflexive abstraction. This will mean that what lies beyond postmodernism will not be naïve to cultural theories about the postmodern—nor, indeed, about itself. Unlike less self-reflective moments in cultural history, metamodernism cannot simply be about naming trends in cultural production, since trends in cultural production themselves now include reference to cultural theory. No, metamodernism must also be about cultural theory—that is, a cultural logic of cultural logics. Theory is no longer an abstraction to explain the concrete; it is now what makes up the concrete artifact itself. Metamodernism is a cultural logic precisely in being about postmodernism and other cultural logics. In a culture increasingly the product of the double hermeneutic, going meta means achieving a triple hermeneutic, a self-reflective stance decentered from and thus able to objectify and navigate the former. Metamodernism is what you get when cultural theory blurs into culture itself.

In sum, what “metamodernism” speaks to, I am suggesting, is 1) the cultural moment when the deep recursive process of iterative self-reflection is applied to postmodernism, and thus constitutes an advance beyond the postmodern that includes many of its strategies. In the process, metamodernism becomes 2) the cultural moment when this deep recursive process in cultural shifts becomes an explicit object of reflection and the basis of a new way of seeing. Metamodernism thus becomes a cultural logic about (meta) cultural logics. Thus, with the awareness of the full implications of “going meta” in eternal recursive reflection, metamodernism entails the necessary inclusion within it of all prior cultural logics (at least insofar as it contains representations of their information in its complexity from a higher vantage). In this way, metamodernism signals an inherently multi-perspectival perspective, one that recognizes its inherent ability to toggle in and out of its own recursive contents.

While postmodernism had recognized plurality, metamodernism recognizes the nested nature of this plurality, the Russian doll structure that allows the metamodernist to relate multiple perspectives to each other and to its own vantage. This is what allows it to move beyond the radical relativity and value nihilism of postmodern pluralism, as transcendence returns as a viable and indeed fundamental aspect of reality. Recursive reflection allows the metamodernist to contextualize different contexts by the ordering and relating of perspectives—including the postmodern one.

That is, if cultural logics proceed out of each other according to an identifiable logic of iterative self-recursion, then one can use this as the standard by which to assess the different cultural logics against one another. Superlatives become possible once again, as now one can speak of the most decentered perspective. One is no longer lost in the relativism of epistemes, since there is at least the ability now to tell where on the scale of relative self-reflection one is. Cultural logics able to master the logic of others by self-recursively applying those logics to themselves to yield new insights reveal themselves as being more critical, more complex, more informationally rich. In short, while there is no absolute standard by which to judge a cultural logic, there is a relative one: namely, How many of the other cultural logics it can nest within its own logic. The more perspectives it can take—and non-arbitrarily relate—is the measure of its complexity and depth, the marker of its advance along a trajectory of infinitesimal progress.

With the postmodern perspective now reified like all the rest, it becomes objectified as an available (but not absolute) lens in its arsenal of different lenses. That is, its lens no longer dominates the entire field of vision. Postmodern skepticism and relativism are a way of seeing—and a highly complex one at that—but not the only way. And, indeed, by its ability to take the postmodern relativist view, but then reduplicate its own logic on itself in such a way as to engender a nonrelativistic vantage that relativizes relativism and contextualizes contexts, metamodernism proves its superiority to the less critical, less self-aware lens of the postmodern. Compared to the metamodern, the postmodern is still employing a particular lens uncritically as an absolute and has not yet decentered enough from its perspective to take it as an object. Metamodernism, though, can take postmodernism as an object, getting outside its vantage in a manner that allows it to recursively apply its own logic to it, and thereby produce something new.

In sum, metamodernism reflects a cultural logic of cultural logics. It is the cultural logic in which the recursive reflection driving the advance of cultural logics becomes itself an object of awareness within the cultural logic. It signals the advance to a perspective that can take perspective on the advance of perspectives. It thus regains modern-style directionality and progress, but without its totalizing impulse. For it arises through an eternal self-transcendence to an awareness of eternal self-transcendence that, as soon as it is realized, abolishes its own status among the transcendent by becoming aware that it will be transcended. It thus represents the transcending process becoming aware of itself and, just as soon as it is seen, passes into the immanent, the finite, the untranscended—

Wait. Stop. That’s too much. Let’s not get all Heideggerian or Hegelian continental bullshit here. (We’ll save that for the considerations of metamodern religion at the end!) For now, let’s keep this grounded…

Okay.

Hopefully it’s clear just what “meta” I mean in my formulation of metamodernism. More will become clearer as I develop the argument by means of other theories of the metamodern. Indeed, the point I’d like to make over the following pages is that this framing actually helps unite and synthesize the various other articulations of the term. That is, with this sense of “meta” as our touchstone, we can begin to see how other formulations of the metamodern articulate versions or subsets of this recursive process, and relate to one another in a way that would remain opaque if we only worked with this or that definition of the term.

Through the lens of recursive transcendence through iterative self-reflection, we can see how and why the metamodern emerges as it does in culture, from art to philosophy to science and beyond. We can see how sensibility and “structures of feeling” shift through different levels of self-reflection; how deconstruction invites a project of reconstructively deconstructing deconstruction while suggesting how the impasse of postmodern skepticism can be transcended through being skeptical of its skepticism; how models of complexity and emergence offer models of this phenomenon in the rest of the natural world; and even how all of this gestures towards a “scale-invariant” kind of meaning-making that explains the nature of transcendence across cultural logics in a manner consonant with the mystical traditions of the great religions.

Woah.

Clearly, the theory of metamodernism I am presenting here is broad, cutting across numerous fields and disciplines. This makes it more comprehensive but also more audacious than the other theories it synthesizes, some of which rather conservatively confine their subject to a cultural period or an academic paradigm. It’s fine for them to do so, and probably necessary for their purposes. For my part, though, I see metamodernism—like modernism and postmodernism before it—as representing nothing less than a comprehensive worldview, since it constellates a particular world model and normative orientation according to relatively coherent principles. It is, that is, a worldview organized according to recursive transcendence through iterative self-reflection—a going meta after and on the postmodern, which naturally brings with it a given sensibility, philosophical project, and meaningful scientific metanarrative as necessary byproducts.

To see the details of all of this, and make the case for this inclusive view of metamodernism, we’ll consider how this basic framework is reflected or presumed in the current major articulations of metamodernism. By doing so, I don’t mean to suggest that all current formulations of metamodernism are saying exactly the same thing. They’re not. They are, though, all speaking about the same thing, getting some things right while missing others. Triangulating all the theories allows us to see just what it is that they are all gesturing to, even as none currently puts their finger on it entirely.

This book is an attempt to identify that thing, to put its finger on the shared object of analysis—to see the full elephant, as it were. Like all theories and all knowledge, it is provisional—but hopefully still infinitesimal progress. To this end, I’ll be taking each of these theories in turn to see how they express, in their own terms and domains, this cultural logic of recursive transcendence. I’ll start with the first articulations and defense of the category, which appeared in the field of cultural studies. Next, I’ll examine the discourses that frame metamodernism as both part of and about a social complexification process. Then I’ll look at metamodernism as a proposed new research paradigm grounded in a novel systematic philosophy. From there, I consider how some metatheorists relate metamodernism to their scientific unified theories. Finally, I conclude with an argument for understanding metamodernism as a comprehensive worldview, with bearing on all aspects of life. In each of these major metamodernist frameworks or applications, we will see how they speak to versions of the same logical pattern: a pattern of recursive reflection.

NEXT: Metamodern Aesthetics

Buy the full book HERE.

NOTES

[i] Robin van den Akker, Alison Gibbons, Timotheus Vermeulen (eds.) (2017) Metamodernism: Historicity, Affect and Depth after Postmodernism (Rowan & Littlefield, London).

[ii] Hanzi Freinacht (2017) The Listening Society, Metamodern Guide to Politics, vol. 1 (Metamoderna, Copenhagen).

[iii] Lene Rachel Andersen (2019) Metamodernity: Meaning and Hope in a Complex World (Nordic Bildung, Copenhagen). (Though see note 16 on p. 201.)

[iv] Jason Ānanda Josephson Storm (2021) Metamodernism: The Future of Theory (University of Chicago Press, Chicago).

[v] “Meta,” Merriam-Webster.com, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/ meta.

[vi] “Meta,” Wiktionary, https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/meta-.

[vii] Also for meta (μετά), we might say (for the sake of complete prepositional thoroughness) that metamodernism entails being…

“in the midst of”: multiple perspectives

“concerning succession”: of multiple perspectives

“concerning pursuit”: of the ever-receding “ultimate” perspective

“concerning letting go”: of any “ultimate” perspective

“reversely”: looking back to anticipate what is ahead

“behind”: the next iteration

“after”: the last one

“concerning change in position or condition”: from one perspective to the next.

[viii] For an earlier consideration of metamodern responses to recursive reflection with special reference to the work of Kierkegaard, see vol. 3 of my Metamodern Spirituality Series, The Oil and the Lamp.

[ix] From her poem “Some Keep the Sabbath Going to Church.”

Really helpful summary of this emerging term. Definitely getting me closer to purchasing your book heh

Your review of postmodernism has me wondering if it is truly best understood as a paradigm that is independent of not only modernism, but distinct from premodern paradigms. It seems like postmodernism parallels other philosophical turns in the last stages of long-gone empires, when their Gods/first values/principles lose their vitality and hyperrational critique and relativism takes hold among its elites -- which is how I've been told to understand sophistry and stoicism at least.

If this is the case, metamodernism is an attempt to rescue the best of (pre)modernity from the self-satisfied cynicism that dominates late modernity, not necessarily a new paradigm either. Haven't pre-modern thinkers also tried to reconcile the apparent naivete of dead axioms with heady rigor before?

If nothing else you've inspired me to look more into this, so thank you for that.