Origins of Metamodernism, Part I

The Birth of Metamodern Discourse in Cultural Studies

The term “metamodernism” first appeared in the academic field of cultural studies as a way for cultural theorists and art critics to conceptualize and frame novel cultural developments since postmodernism. This discourse took off following a seminal paper in 2010 entitled “Notes on Metamodernism” by two Dutch cultural theorists who offered important insights about these developments and a new rubric for assessing post-postmodern artworks. This chapter will be devoted primarily to their framework, and subsequent work in that lineage. However, earlier uses of the word, some relevant and some not, warrant consideration as notable precursors in light of the term’s popular adoption since 2010. I’ll begin, then, with a cursory look at some of these before turning to the mainstream metamodern aesthetic discourse.

Pre-2010 Precursors / Intimations of Integration

The first documented use of the term “metamodern” goes back to 1975, when critical theorist Mas’ud Zavarzadeh employed it to speak of a certain kind of (then) contemporary novel struggling with the increasing blurring of reality with the fantastic and fiction-like qualities of late 20th century life. A reading of Zavarzadeh’s essay “The Apocalyptic Fact and the Eclipse of Fiction in Recent American Prose Narratives”[i] makes clear, however, that this neologism was simply an attempt to name one emerging trend within postmodern literature—specifically, one that abandoned any attempts at meaningful interpretation of reality in light of its perceived absurdity. Zavarzadeh’s category of “metamodern” novels, then, referred to something quite different than the contemporary metamodern discussion—a trend now captured quite comfortably under the category of postmodernism. His ideas thus don’t form part of the intellectual lineage of the current discourse, so let’s move on.

A bit more germane is the work of art historian Moyo Okediji, who, writing about Black artists of the African diaspora in 1999, employed the term “metamodern” to reference works that lie beyond or outside the established modern/postmodern academic discourse of Western art. In response to this too simplistic binary, Okediji posited the “metamodern” as an “extension of and challenge to modernism and postmodernism,”[ii] particularly in contexts where colonial histories have produced idiosyncratic hybrids and creoles. With the “metamodern,” he offers a category “inclusive of and transcending all forms of modern myths” (with “myths” here referring to all manner of cultural movements, conceptual paradigms, taxonomies, etc. such as existentialism and postmodernism).[iii] In this sense, the idea of the metamodern is meant to open up alternative modernisms not captured in the allegedly colonialist Western discussion privileging modernism and postmodernism as the principal terms of debate. Okediji’s work is compelling, and has been seminal in its own way (via Storm, as we’ll see), but as a precursor to contemporary metamodern discourse it has historically been (perhaps ironically) largely beyond or outside the main stream of discussion owing to its more particular concern with African art. With the widening scope of contemporary metamodern discourse, though, this may be changing.

Moving on, we find another early use of the term “metamodern” in literary scholar Andre Furlani’s attempt to identify a group of mid- to late-20th century writers who seemed to straddle both modernist and postmodernist sensibilities. In a 2002 essay,[iv] and a later 2007 book,[v] Furlani focused on Guy Davenport (1927-2005) as representative of this group who, though early identified with the label, eventually fell out of “postmodernism” as the term came to be more associated with poststructuralist and anti-realist stances. As Davenport himself would reflect: “I come too late as a Modernist and too early for the dissonances that go by the name of Postmodernism.”[vi] In hindsight, it is now clear that these “metamodernists” can be better understood as reflecting residual modernist sensibilities, not what we would call nascent metamodernist ones,[vii] though this is debatable. Furlani’s analysis, then, is also not part of the lineage we are speaking to.

The use of the word by comparative studies scholar Alexandra Dumitrescu, however, is most compelling as a legitimate precursor to the metamodern discourse now underway. In her prescient 2007 essay “Interconnections in Blakean and Metamodern Space,”[viii] Dumitrescu offers a coherent analysis of a “metamodern” modality that has significant overlap with later theorizations. Specifically, she sees metamodernism emerging from/constructively responding to (post)modern fragmentation with an integrated pluralism that embraces multiple, provisional maps of reality’s many levels while reinfusing life with meaning, emotion, and story. She writes:

Positing metamodernism as a period term and a cultural phenomenon, partly concurring with (post)modernism, partly emerging from it and as a reaction to it (especially to its fragmentarism, individualism, excessive analyticity, and extreme specialization), I shall also attempt to outline several features of metamodernism as a budding cultural paradigm. Allowing for diverging theories, metamodernism champions the idea that only in their interconnection and continuous revision lie the possibility of grasping the nature of contemporary cultural and literary phenomena.[ix]

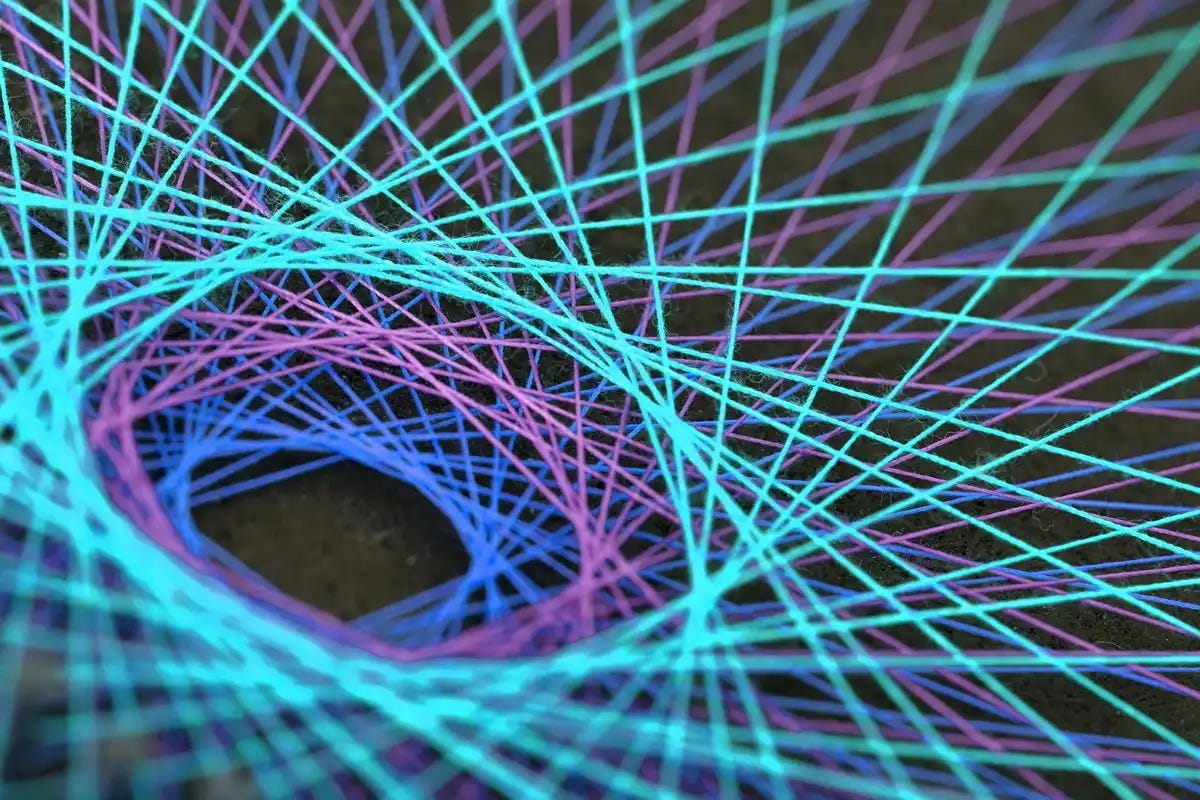

Dumitrescu’s metamodernism thus emphasizes what she calls connectionism, the bridging of many diverse ways of seeing together into a more holistic vision that allows for these different perspectives to productively co-exist. In this way, she says, metamodernism moves beyond postmodernism’s simple recognition of incommensurable multiplicity by working to build these different outlooks into an interconnected network. She observes:

Postmodernism, for example, acknowledged the existence of peripheral outlooks, but a certain tendency towards integration of diverse points of view and of placing them in fertile dialogue, surpasses postmodernism. Whereas fragmentarism characterises postmodernism, integration is a feature of metamodernism. However, postmodernism and metamodernism are not mutually exclusive.[x]

With this remark, Dumitrescu recognizes that the postmodern perspective is itself part of metamodernism’s broader network of viewpoints. The postmodern view can do some things better than others and remains an open, viable option. In our terms, the metamodern can toggle to the postmodern outlook when appropriate, even as the metamodern mode contains that outlook as part of a broader nested network of perspectives. In this way, says Dumitrescu, different theories “overlap,” and the metamodernist recognizes that there is no need for epistemological exclusivity when it comes to different perspectives.

The ongoing process of building of a more comprehensive and open set of perspectival connections is what Dumitrescu calls “bootstrapping.” This is one of the key components of her metamodern outlook, noting that

connectionism (as a mode of thinking), bootstrapping (as a way of identifying connections) and the principle of theory overlapping are but aspects of metamodernism.[xi]

With bootstrapping, different epistemologies become linked together in an ongoing process of connective construction, each forming part of a more coherently integrated network of perspectives. “The components of the bootstrap model,” she says,

are linked or interwoven in a network that indicates the connections between theories, paradigms, or cultural trends. Thus different theories may be simultaneously relevant for an issue considered. To put it another way: several theories regarding the same issue(s) can co-exist, their interplay pointing to the complex nature of the phenomena considered.[xii]

In this way, Dumitrescu leans on images of network, web, and system to articulate her sense of metamodernism. This is interesting, as later theories of the metamodern will come to emphasize just these sorts of metaphors, drawing on complexity science and systems theory to frame the recursive shifting of cultural logics in human history (see Chapter 3).

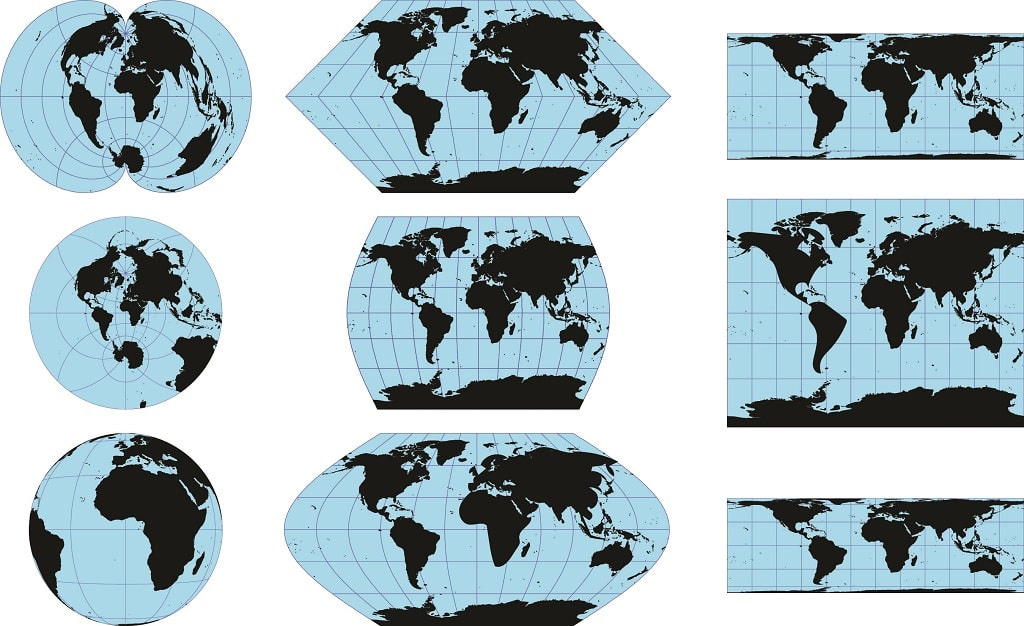

Dumitrescu employs some other particularly evocative images to capture this ongoing constructive process of metamodern bootstrapping. Borges, she notes, gave us a classic example of the postmodern approach to navigating the world: a map which, in order to capture every single individual particularity of the terrain, winds up being just as big as the landscape it would depict! In the postmodern epistemology of radical fragmentation and particularization, the plurality dominates over generality and abstraction. The metamodern map, she says, is different:

Thus, as opposed to the postmodern accurate map grown until cumbersome, the metamodern space may be represented as a set of maps under continuous revision, each map of the set focussing [sic] not only on accurate representation, but also on pinpointing connections between various points of reference. Another fit metaphor may be that of a boat being built or repaired as it sails, or a palace or house under continuous construction.[xiii]

The metamodernist thus possesses a plurality of maps, fit for different uses, yet connected to one another to form a coherent, integrated vision of a reality forever under representational construction. This is the orienting work continually being built and rebuilt.

One should see clearly how this notion of metamodernism relates to my emphasis on infinitesimal progress. The ultimate representation is continually moved towards but never fully or finally attained. Metamodern epistemology is not about gaining Absolute Knowledge (as the modernists sought), nor about abandoning the possibility of knowledge entirely in the face of radical multiplicity (as the postmodernists did), but rather embracing the never-ending approximation of reality’s diverse terrain through continually adding to and updating one’s various maps of it. Nesting more and more perspectives into a network of diverse yet integrated viewpoints gives us more and more of the bigger picture. But the process never ends; the palace is always under construction. Mapping the world is a continual bootstrapping process, forever building off of previous levels. This is the nature of cultural evolution itself, which is continuously generating new paradigm shifts in its punctuated equilibrium towards a receding telos.

Indeed, in a later work, Dumitrescu suggests as much, writing: “Metamodernism affords an integrative perspective from which paradigms appear as steps in an evolutionary process.”[xiv] Employing the classical language of Hegel in her 2010 essay “Foretelling Metamodernity” to talk about metamodernism’s emergence in this process, she identifies it squarely as the synthesis of modernism and postmodernism:

[A]s far as its relationship with modernism (the thesis) and postmodernism (anti-thesis) is concerned, metamodernism incorporates their achievements, but surpasses both in a type of synthesis.[xv]

Indeed, reflective of this synthesis, Dumitrescu’s metamodernism marks a return to meaning and story—crucial aspects of modernist grand narratives that came to be undermined by postmodern reflection, here reclaimed by means of connection. The very pluralism of perspectives inaugurated by postmodernism becomes the necessary basis for the endeavor to connect truths defining the metamodern sense of narrative and meaning. Metamodernism, she says,

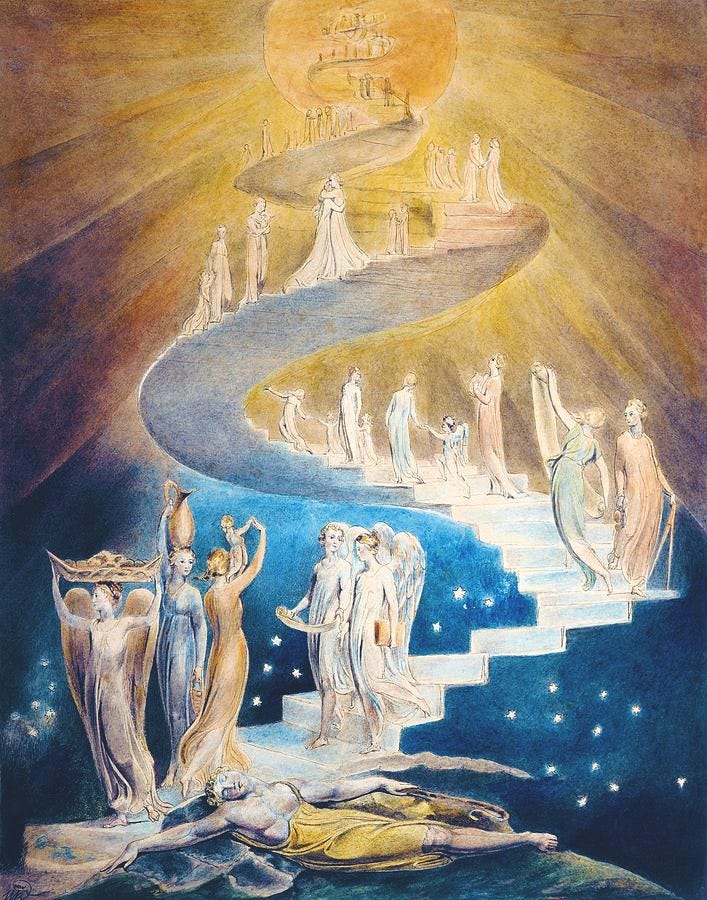

is a turn towards the story that bridges gaps between levels of existence. Not so much the story as an epistemological endeavor, but the story as a link between humans and (distinct) ontological levels. An apt metaphor for this may be Jacob’s ladder, on which angels climb and descend, establishing connections and interceding between high and low, between created and uncreated, between reality, if you want, and fiction, between factual and imaginative existence. …Metamodernism, then, is the struggle to find meaning, and in searching for meaning, it is the tendency to re-establish that connection or those connections that would render life and creation, love and expression meaningful.[xvi]

The image of Jacob’s ladder is yet another compelling representation of the sort of leveled reality posited by eternal recursion, according to which one can move up and down to different perspectives and modalities, toggling between truths that identify different aspects of the world. The goal is not to reach the “top,” since no such top exists—lost in the clouds of heaven. Rather, the goal is to bridge the levels, to ascend and descend, to deepen the ties between real and imaginal, “heaven and earth,” finite and infinite. The telos is not where the ladder ultimately leads, but in the process of traversing it. Indeed, one might add to the images of ship and palace the continual construction of the ladder itself as an example of “bootstrapping.” One forever continues adding new rungs to the ladder one stands on to increase one’s vantage on the world.

A short but evocative blog post written by Dumitrescu in 2013 entitled “Metamodernism. A Few Characteristics” captures much of the foregoing analysis in succinct terms, and is worth reproducing in its (near) entirety. In it, Dumitrescu articulates a metamodern shift defined by a reclamation of immediacy amidst hyper-reflection, an integrative approach aimed at connecting multiple cultural logics and epochal wisdoms, and a return to meaning within a collective network of different meaning-making systems. She writes:

Metamodernism is the search for roots in times of uprootedness. It is the being’s longing for innocence, beauty, and simplicity in times of sophistication, shifting aesthetic standards, and complexity. It is the search for that vantage point from which both complexity and simplicity can make sense, coexist, and complement one another.

From the perspective of metamodernism, the respective values of cultures, paradigms, theories, and strategies, as well as their interconnectedness, may be assessed.

Metamodernism synthesises the best from modernism and postmodernism: the modernist interrogations of the roots and validity of traditions, challenging rationalism and useless rules or systems, the insistence on imagination and inspiration – coexist side by side with the postmodern openness to dialogue, its multiculturalism and inclusiveness of the other (women, minority groups, indigenous people), challenging hierarchies and metanarratives, merging of art forms, interest in Everyone’s life and the context of his/her existence.

Metamodernism is a return to fundamental questions that define our being in the world. It is the integration of experience with innocence and wisdom, of reason with sensibility, of past with present. It is a search for the meaning and beauty of the present.

Metamodernism integrates the lessons of the past to enrich the present. It transcends national boundaries and ethnic divisions to identify the determinants of the subject in the twenty-first century. It is a poetics of tolerance, appreciation, and acceptance of the other, with openness and kindness.

Metamodernism is the search for the truths that live, and have always lived, within the hearts of everyone. It acknowledges the value, playfulness, and necessity of mask-wearing, in harmony with the importance of self-knowledge in the Socratic sense.

Metamodernism is a bold assertion of the human being as a spiritual entity, rather than a forlorn person inhabiting his or her detached island of individualism. Each person is recognised as part and parcel of the whole of human society and history, an essential part of a system of networks of continuous dynamism in the animate and inanimate world.

Metamodernism is a self-perception of humans in their complexity, in their infinite combinations and permutations of emotions, reason, conditionings, and ego – yet metamodernism seeks the common denominator that makes communication possible within our humanity: respect for nature, for the self and for the other.

Metamodernism is the expression of the self’s search for home…[xvii]

Dumitrescu’s later work comes to place even greater focus on self-realization, emotion, and connective care, but the above themes in her early work stand out to me as prescient insights about the metamodern paradigm as it would also come to be framed by multiple later theorists. While her analyses consider a variety of artistic examples, including contemporary ones like Arundhati Roy’s 1997 The God of Small Things, it is also true that her notion of the metamodern extends, as a sensibility, to much earlier artists (e.g., William Blake), which complicates her discussion of metamodernism as a period. Indeed, one of the critiques of her work is that it would appear to be operating not so much as a description of a particular cultural logic grounded in a systematic study of a specific kind of cultural production, but an aspirational prescription for a timeless mode of being.[xviii] Still, despite these valid criticisms, her work stands as an important precursor to the first major current of metamodern discourse, which was officially inaugurated in 2010 by two Dutch theorists, Timotheus Vermeulen and Robin van den Akker.

NEXT: Part II

[i] Mas’ud Zavarzadeh (1975) The apocalyptic fact and the eclipse of fiction in recent american prose narratives. Journal of American Studies 9(1):69-83.

[ii] Moyo Okediji in Michael Harris (ed.) (1999) Transatlantic Dialogue: Contemporary Art In and Out of Africa (University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill), 49.

[iii] Moyo Okediji (1999) Black skin, white kins: Metamodern masks, multiple mimesis. In Nicholas Mirzoeff (ed.) Diaspora and Visual Culture: Representing Africans and Jews (Routledge, London), 162, n. 1.

[iv] Andre Furlani (2002) Postmodern and after: Guy Davenport. Contemporary Literature 43(4):709-735.

[v] Andre Furlani (2007) Guy Davenport: Postmodern and After, Avant-Garde & Modernism Studies (Northwestern University Press, Evanston).

[vi] Furlani 2007, 709.

[vii] Furlani writes: “A designation as postmodernist can only distort the work of writers like Davenport, who are better viewed as metamodernists. The English prefix meta- relevantly denotes derivation, resemblance, succession, and change. The Greek preposition from which it derives has an especially pertinent range of meanings: with the accusative, it means "after" or "next"; with the dative, "among," "besides," or "over and above"; with the genitive, "by means of" or "in common with." The metamodernists develop an aesthetic after yet by means of modernism. Where post- suggests severance or repudiation, meta denotes the continuity apparent in the metamodernists' efforts to succeed the modernists. The metamodernists seek with the help of modernism to get over and beyond it” (Furlani 2002, 713).

[viii] Alexandra Dumitrescu (2007) Interconnections in Blakean and metamodern space. Double Dialogues 7, https://doubledialogues.com/article/interconnections-in-blakean-and-metamodern-space/.

[ix] Dumitrescu 2007.

[x] Ibid.

[xi] Ibid.

[xii] Ibid.

[xiii] Ibid.

[xiv] Alexandra Dumitrescu (2016) What is metamodernism and why bother? Meditations on metamodernism as a period term and as a mode. Electronic Book Review, 8.

[xv] Alexandra Dumitrescu (2010) Foretelling metamodernity: Reformation of the self in Jerusalem, Messi@h and Rosarium Philosophorum. Working paper, 5.

[xvi] Dumitrescu 2007.

[xvii] Alexandra Dumitrescu (2013) Metamodernism. A few characteristics. Medium (December 26), https://metamodernism.wordpress.com/2013/12/26/metamodernism-a-few-characteristics/. I am indebted to Marshall Æon for directing my attention to this post.

[xviii] Timotheus Vermeulen and Robin van den Akker (2015) Misunderstandings and clarifications. Notes on Metamodernism (June 3), https://www.metamodernism.com/2015/06/03/misunderstandings-and-clarifications/.

I have an easy on the topic published in The Republic of Letters today and a reader said I should come check you out. 😀

Thanks for the generous share. I have several of your books but it is good to have digital resources which make sharing more easy.