Political Conformity & the Developmental Constraints on Democracy

A Polarized America in the Grip of 3rd Order Consciousness

Human beings are social animals. It is in our nature to form groups and to see our group membership as critical to our identities as individuals. (Indeed, this is actually a key part of the developmental process.) Unfortunately, though, this form of socialization can come with a severe tradeoff: the loss of autonomous thinking. Simplistically put, the more an individual is subsumed into a group, the more in danger they are of ceding their thinking to the collective. Here, intelligence can offer no immunity or defense, as even the most intelligent can prove just as susceptible to this mind-numbing dynamic.

While the phenomenon has long been noted, recognized by philosophers and statesmen alike since antiquity, it wasn’t until the late 19th century that social scientists began to examine the scope of this syndrome. Gustave Le Bon’s The Crowd was one early and influential work on the topic. In the 1895 text, Le Bon noted how, once formed, a crowd has what we might call “a mind of its own”—one animated by unconscious sentiments and completely impervious to rational argumentation.

The most striking peculiarity presented by a psychological crowd is the following: Whatever be the individuals that compose it, however like or unlike be their mode of life, their occupations, their character, or their intelligence, the fact that they have been transformed into a crowd puts them in possession of a sort of collective mind which makes them feel, think, and act in a manner quite different from that in which each individual of them would feel, think, and act were he in a state of isolation.[i]

Here, it seems, individual intelligence goes out the window. People, all people, can become, as a whole, highly suggestible, eager to be led, and irrationally dogmatic. Le Bon is explicit:

the mental quality of the individuals composing a crowd must not be brought into consideration. This quality is without importance. From the moment that they form part of a crowd the learned man and the ignoramus are equally incapable of observation.[ii]

Twentieth century social scientists have since fleshed the bones of Le Bon’s assessment with empirical data. In their work on democracy, Achen and Bartels cite two notable examples of studies in group psychology: the Asch conformity experiments and Henri Taifel’s studies on prejudice.

In 1951, psychologist Solomon Asch

asked a group of previously unacquainted male undergraduates to judge which of three line segments was closest in length to a fourth reference line. Left to themselves, more than 99% of students gave the correct answer. But in groups, the outcome was quite different. Unbeknownst to the experimental subjects, the other group members were confederates of the experimenter, instructed to give wrong answers at some points in a sequence of trials. The confederates were seated so that they spoke first, leaving the remaining student to either give the correct answer in defiance of everyone else, or to go along. A large majority of the experimental subjects conformed on at least some of the trials, and some [37%] conformed all the time. In debriefings afterward, the conformists ranged from those who knew their answers were wrong but thought they should go along, to those who felt their eyes must be deceiving them and so adopted the group’s perception. A few subjects conformed so completely that they professed not even to have noticed the evidence from their own eyes.[iii]

What Asch’s studies reveal is the propensity for group pressures to override rational thinking—indeed, even to the point of affecting individuals’ perception of reality itself.

This last point is remarkable. In 2005, researchers repeated a version of Asch’s experiment, this time with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Jason Brennan reports:

By monitoring the brain, they [sought] to tell whether subjects were making an “executive decision” to conform to the group, or whether their perceptions actually changed. The results suggest that many subjects actually come to see the world differently in order to conform to the group. Peer pressure might distort their eyesight, not just their will.[iv]

As an individual, a person might be rational, but once in a group, critical thinking can recede; the truth of the group takes over. Indeed, the group can even be said to “think for” the individual.

In an evolutionary context, such dynamics have clear adaptive advantages, allowing a high degree of coordination for a more effective social superorganism. In the context of modern political discourse, however, it can be downright pathological to the body politic, turning would-be critical thinkers into conformist zombies spouting group-think and shutting down the means of rational debate.

For instance: Trump’s boasting about sexually assaulting women by grabbing their genitals? Just locker-room talk. His mean-spirited narcissism? He’s just a New Yorker. His racism and sexism? At least he tells it like it is! That whole January 6th attack on the Capitol? Come on, that wasn’t a “coup”! Just some peaceful, patriotic tourists protesting a stolen election. (Or perhaps a false flag operation altogether…)

Meanwhile, we are told that those occupying indigenous lands who do not publically renounce their whiteness as a cancer and own their fragility and privilege to proclaim explicit allyship with BIPOC, Lantinx folx, and wxman are bigots who must be silenced. Words to the contrary are violence; disagreeing is oppression; even asking questions is a micro-aggression. See you at drag queen storytime at church! (unless, that is… you’re some sort of close-minded homophobe who hates all queer people…?)

This tendency for people to lose nuance, open-minded tolerance to different points of view, and clear-eyed critical-thinking skills when identifying with a group becomes even more disconcerting when paired with the insights from Henri Taifel’s studies.

In his experiments, people arbitrarily assigned to meaningless groups quickly began to favor their fellow group members against others, even when they knew nothing about anyone else involved, they themselves did not profit from their bias, and no prior group conflict had occurred. This “minimal group” paradigm demonstrated that the human capacity for joining groups and disliking other groups was close to the surface and easily mobilized…[v]

Randomly finding yourself on “the red team,” you are more inclined to experience not only a significant and entirely nonrational sense of connection with your other team members, but also an antipathy directed toward “the blue team”—and vice versa. Such prejudices are purely instinctual responses, completely disconnected from anything like informed, rational thought—indeed, running precisely contrary to them! “Identities are not primarily about adherence to a group ideology or creed,” write Achen and Bartels. “They are emotional attachments that transcend thinking.”[vi]

In short, even though many people might be capable of thinking intelligently, they don’t. Something gets in the way, and that something is group conformity. Religion, race, class—such markers become far more salient in political discourse and at the ballot box than anything like an informed and rational endorsement of a policy or candidate. And, more than ever, the group affiliation proving to be the most compulsive of all is political party.

But wait! Don’t people support a particular party because of what they think about policies and issues?

As it turns out, no. It’s just the opposite, in fact. People largely think what they do about policies and issues because of the particular party they support. Achen and Bartels explain:

Partisanship, like religious identification, tends to be inherited, durable, and not about ideology or theology. …[P]eople are often adherents of a particular political party because their great-grandparents favored it for entirely different reasons. That in turn helps to explain why partisan leanings are often only modestly correlated with policy preferences. …[C]areful efforts to disentangle their reciprocal effects…suggest that ideology is more often an effect of partisanship than its cause.[vii]

A host of factors might be at play for why a person votes Republican or Democrat; but more often than not, these factors will be based less on one’s perspective on the proper role and size of government, say, and more on who their close friends and imagined community support; less on views about the separation of church and state and more on whether the candidate goes to a church that’s like theirs. “For most people,” write Achen and Bartels,

partisanship is not a carrier of ideology but a reflection of judgments about where “people like me” belong. They do not always get that right, but they have much more success than they would constructing their political loyalties on the basis of ideology and policy convictions. Then, often enough, they let their party tell them what to think about the issues of the day.[viii]

Just like the students in Asch’s experiment, many citizens capable of forming their own informed opinions nevertheless defer to their party for what to believe. Even if what they hear from their group flies in the face of their own experience, contradicts what the group used to say, or otherwise flouts rationality, people will conform—whether as those who know their answers were wrong but thought they should go along, as those who felt their eyes must be deceiving them and so adopted the group’s perception, or as those who conform so completely that they can no longer even see the evidence with their own eyes.

Achen and Bartels describe the process with dismal accuracy:

[E]ach party organizes the thinking of its adherents. A party constructs a conceptual viewpoint by which its voters can make sense of the political world. Sympathetic newspapers, magazines, websites, and television channels convey the framework to partisans. That framework identifies friends and enemies, it supplies talking points, and it tells people how to think and what to believe. …Once inside the conceptual framework, the voter finds herself inhabiting a relatively coherent universe. Her preferred candidate, her political opinions, and even her view of the facts will all tend to go together nicely. The arguments of the “other side,” if they get any attention at all, will seem obviously dismissible. The fact that none of the opinions propping up her party loyalty are really hers will be quite invisible to her. It will feel like she’s thinking.[ix]

Gregg Henriques, a professor of psychology at James Madison University, identifies “collective justification systems” as networks of claims that cohere individual psyches with(in) social groups. Identity is formed through exchange with communally processed frameworks for meaning-making. This is a helpful way to understand such political worldviews, and I would suggest that their dynamics of formation can be more or less emergent.

More decentralized formations of justification systems can emerge through dynamics akin to starling murmurations, as each individual locally responds to their context in such a way as to produce patterned characteristics at the level of the whole. Such dynamics can create runaway feedback loops, driving polarization in the process. (This is how leftist revolutions come to “eat their own,” for instance, as individuals jockey to outradicalize one another and, in the process, slip ironically into authoritarian postures.)

Other justification systems are more centralized and “top down,” as political parties more or less directly craft the thinking of adherents through relentless propaganda machines. Nowhere is this process better illustrated than in a media apparatus like Fox News. One can spend all day tuned in to its 24-hour “news cycle,” listening to the rotation of anchors and pundits, and on into the evening opinion shows, all the while presuming that one is meaningfully engaging the facts and the political process as an informed citizen—when, in reality, one is only being spoon-fed talking-points and steered by the propaganda machine of the Republican Party. The degree to which its conservative viewers have fallen in line behind Donald Trump will likely become a textbook example of the way in which a party can “organize the thinking of its adherents.” How neoconservative ideologues of free-market globalism could so soon switch to fawning over anti-war America First protectionism, or how “family values” Evangelicals could so ardently come to adore a coarse, philandering nihilist is all but unintelligible outside the interpretive framework we are discussing here. These radical metamorphoses are incomprehensible if one considers the electorate to be comprised of anything remotely resembling informed citizens coming to reasoned policy positions; they are, though, understandable (if disturbing) if one appreciates the degree to which the party shapes its members’ thinking.

While this idea sounds almost too cynical to be believed, it is, alas, what the evidence bears out. Citing the mid-century work of Lazarfield, Berelson, Gaudet, and McPhee,[x] Achen and Bartels note that “[t]he Columbia scholars showed that group membership…powerfully shaped vote choices. People adapted their ideas to those of the presidential candidate they favored, or if they were less informed, they simply assumed (sometimes incorrectly) that his ideas matched their own.”[xi] Meanwhile, the seminal study of voting behavior, The American Voter (1960) by Campbell et al., showed that “group memberships largely drove policy views, not vice versa.”[xii]

Ultimately, it doesn’t take a social scientist to come to this result; a late-night comedian can do it.

The comedian Jimmy Kimmel…stopped people on the street, and asked them which of the tax plans offered by Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump they preferred. The interviewees, however, did not know that Kimmel had switched the details of each plan. As The Hill newspaper later reported, the answers depended on whom people thought they were supporting: “Sure enough, one by one, the Clinton voters were stunned to discover that they were vouching for the proposal of her archrival.” …When [The Huffington Post’s polling director Ariel Edwards-Levy] and her colleagues conducted a more formal version of the Kimmel ambush, they found the same thing: Republicans who strongly disagree with Democratic Party positions on health care, Iran, and affirmative action objected far less if they thought the same policies were those of Donald Trump. Democrats, for their part, went in the other direction: they were less supportive of their own party’s policies if they thought they were Trump’s positions.[xiii]

Jason Brennan wryly but accurately reflects, “If the rivalry between Democratic and Republican voters sometimes seems like the rivalry between Red Sox and Yankees fans, that’s because from a psychological point of view, it very much is.”[xiv]

This kind of purely partisan thinking (if it can be called thinking) doesn’t just make people un-informed citizens; in fact, it leads them to be mis-informed. The difference might seem slight, but it’s significant. An uninformed voter is simply ignorant of the truth; a mis-informed one is one’s who’s wrong about it. An uninformed voter can be taught; a misinformed voter refuses to learn because he or she already thinks they’re right.

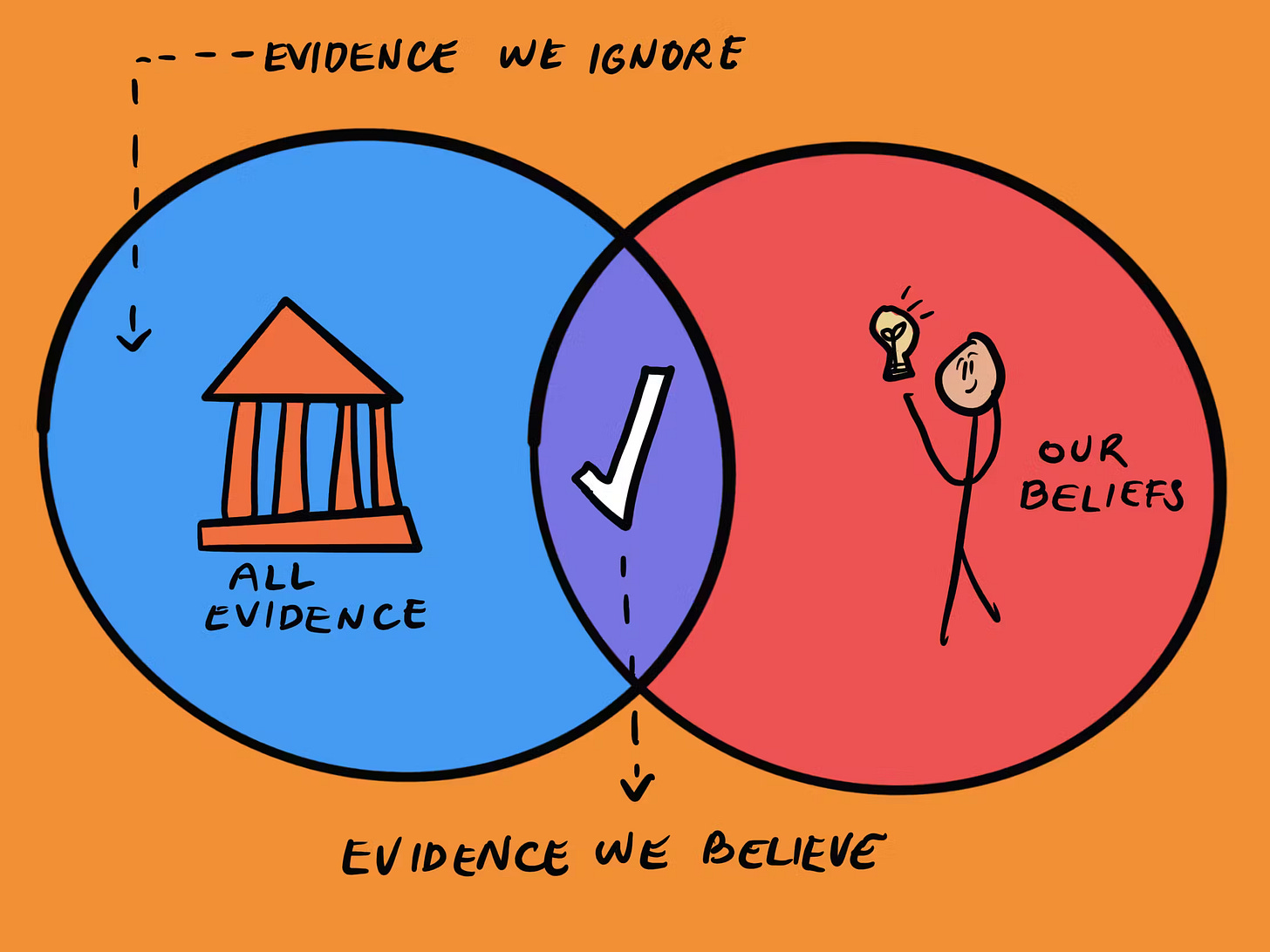

Partisanship makes people stupid—even intelligent people. It does this by overriding our capacity to think rationally through a very common cognitive error: confirmation bias. Human beings have a natural inclination to accept information that fits with our understanding of the world and to reject information that doesn’t. That is, we are biased toward believing things that confirm what we already (think we) know. This instinctual cognitive shortcut may have worked well for us in our evolutionary past, helping us act on established wisdom and experience and eschew anomalous and untried (i.e. dangerous) novelties (“assimiliation” in developmental terms), but in rational, intellectual activities it can be a real liability—one that’s always in our blind spot.

Partisan loyalties will lead even intelligent people to doubt reality before they doubt their party’s position. Nichols writes:

A 2015 study…tested the reaction of both liberals and conservatives to certain kinds of news stories, and it found that “just as conservatives discount the scientific theories that run counter to their worldview, liberals will do exactly the same.” Even more disturbing, the study found that when exposed to scientific research that challenged their views, both liberals and conservatives reacted by doubting the science, rather than themselves.[xv]

“In this house we believe … SCIENCE IS REAL…” Well, sort of. Climate science perhaps. And the science studying the non-efficacy of face masks? research into the uncertainies and potential risks of childhood hormone therapies and gender reassignment surgeries…? For the conformist mind, “science” is something one “believes” and “trusts” in—placing their faith in the holy WHO or almighty AMA—not a method for generating empirical evidence to buttress claims about reality. Meanwhile, precisely those on the right shouting “fuck your feelings!” (presumably in favor of the hard facts) are just the sort to betray a great deal of fact-free, feeling-based thinking when it comes to issues of climate change, failures of the free market, the efficacy and importance of vaccines, election security, and many other issues where overwhelming evidence is quickly dismissed in favor of ideological commitments.

Confirmation bias is powerful—so powerful that it overrules whatever cognitive ability one has, hijacking it for partisan ends. In 2013, Dan Kahan performed an experiment that showed this with shocking precision. Brennan relates:

[Kahan] wanted to answer the question, When laypeople come to mistaken conclusions about social scientific matters, is it because they aren’t smart enough to understand the evidence, or because they are too biased to process the evidence properly? To test this, Kahan recruited a thousand subjects, gave them a basic mathematics aptitude test, and then surveyed their political views. He then asked them to reason through some scientific problems. The first problem was politically neutral [related to a skin cream product]. …Kahan purposely made the mathematics tricky. Not surprisingly, only subjects with high mathematical aptitude scores figured out the right answer. Liberals and conservatives did equally well. …[Then] Kahan reworded the math problem; he made it about gun control as opposed to skin cream. …The math was exactly the same as with skin cream. So presumably people who got the answer right in the first case should get it right in the second. On the contrary, people overwhelmingly concluded that the hypothetical data supported their preexisting beliefs about handguns and crime.[xvi]

Our party loyalties, it seems, are even able to convince us that 2 + 2 = 5! In short, intelligence counts for little when it’s overridden by group allegiances. Through confirmation bias, partisanship makes smart people wrong about reality—not just ignorant of it. Worse, it holds them there with dogmatic inflexibility.

Indeed, Le Bon observed in 1895 what is now a nearly universal experience these days:

Evidence, if it be very plain, may be accepted by an educated person, but the convert will be quickly brought back by his unconscious self to his original conceptions. See him again after the lapse of a few days and he will put forward afresh his old arguments in exactly the same terms. He is in reality under the influence of anterior ideas, that have become sentiments, and it is such ideas alone that influence the more recondite motives of our acts and utterances.[xvii]

Of course, the primrose path of confirmation bias can be abandoned or avoided altogether, provided there is enough information coming in to challenge it (“accomodation” in developmental terms). Unfortunately, one of the most insidious ways that confirmation bias operates is in our very choice of information sources. Here is one area where the electorate has not only maintained its ignorance but actually gotten much, much worse.

The reason? The proliferation of news sources and their fragmentation into consumer niches tailor-made to demographic biases. Nichols succinctly summarizes the process:

Forty years ago…[n]ews organizations had to try to cover the broadest and most demographically marketable audience, and so newscasts in the United States through the 1960s and 1970s were remarkably alike… [But a]ffluence and technology lowered the barriers to journalism and to the creation of journalistic enterprises in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, with predictable consequences. More media meant more competition; more competition meant dividing the audience into identifiable political and demographic niches; more opportunity at more outlets meant more working journalists, regardless of whether they were competent to cover important issues. All of this competition was at the behest of the American consumer, who wanted everything simpler, faster, prettier, and more entertaining.[xviii]

The result has been a “news” source for every ideology: each one with more oversimplification and less integrity than the last. Commodified, news can offer whichever flavor of reality suits the customer’s taste. Parties, seeing news freed from the shackles of objectivity, are only too eager to help meet the demand, providing the best mechanism yet for “organizing the thinking of their adherents.” So the Fox News model becomes the basis for an MSNBC to compete in the marketplace of “news.” Now anyone can have their “alternative facts.”

With the advent of social media, this phenomenon has only become more pronounced. People are obliged to formulate their “bubble.” Nichols records: “A 2014 Pew research study found that liberals are more likely than conservatives to block or unfriend people with whom they disagreed, but mostly because conservatives tended to have fewer people with whom they disagreed in their online social circles in the first place.”[xix] That sounds about right.

Meanwhile, the infinite heap of uncurated information that is the internet has exacerbated things to the breaking point. It offers to billions, at a click, both penetrating journalism as well as rabbit holes of sub-Reddit threads on fringe conspiracy theories and extremist rants—all without a guide, a map, or mentor for your orientation. It is an epistemological No Man’s Land. Though once hailed as an empowering democratic leveler, it has since shown its limitations.

As ever, a tool is only as useful as the skill of the one wielding it. More information does not equate to more knowledge, let alone more wisdom. Here mere data hits a wall. True knowledge requires the filter of interpretation, and this is an art as much as a science. More pencils will not create more artists (a pencil can also be used as a shank, after all).

None of this has stopped us. Armed with ignorance, turbo-charged by confirmation bias, with a large axe to grind on behalf of our groups, we play the internet sleuths and meme-posters and fake news propagators.

All of this, it turns out, is less than futile. “Accessing the Internet,” writes Nichols, “can actually make people dumber than if they had never engaged a subject at all.”[xx] He cites a University of College London study, which found that

people don’t actually read the articles they encounter during a search on the Internet. Instead, they glance at the top line or the first few sentences and then move on. Internet users, the researchers noted, “are not reading online in the traditional sense; indeed, there are signs that new forms of ‘reading’ are emerging as users ‘power browse’ horizontally through titles, contents pages and abstracts going for quick wins. It almost seems that they go online to avoid reading in the traditional sense.” This is actually the opposite of reading, aimed not so much at learning but at winning arguments or confirming a preexisting belief. …“Society,” the UCL study’s authors conclude, “is dumbing down.”[xxi]

That’s not the worst of it. While it’s one thing to discount some facts because they don’t confirm your biases, partisan thinking is capable of more egregious stupidities—even to the point of making up facts altogether. Here’s where partisans prove themselves to be even more stultifying and dangerous than the merely ignorant. For while the ignorant are just as likely to be right as wrong when asked about a political reality, partisan minds usually have just enough knowledge for their confirmation bias to kick in and color reality with their presumptions. Nichols records how a study done by the University of Illinois in 2000

found that “uninformed citizens don’t have any information at all, while those who are misinformed have information that conflicts with the best evidence and expert opinion.” Not only do these people “fill in the gaps in their knowledge base by using their existing belief systems,” but over time those beliefs become “indistinguishable from hard data.” And, of course, the most misinformed citizens “tend to be the most confident in their views and are also the strongest partisans.”[xxii]

As political scientist Danielle Shani puts it, “political knowledge does not correct for partisan bias in perception of ‘objective’ conditions, nor does it mitigate the bias. Instead, and unfortunately, it enhances the bias; party identification colors the perceptions of the most politically informed citizens far more than the relatively less informed citizens.”[xxiii]

In short, when it comes to assessing reality, having some political information is actually worse than being completely uninformed.

Examples range from the mundane to the disturbing. An example of the former pertains to public perceptions of the deficit during the Clinton administration. To well-informed citizens paying attention to the political developments of the day, this was an important issue. The dramatic reduction of the deficit was, in fact, a huge accomplishment to occur under that administration. Nevertheless, the vast majority of the electorate—both Democrats and Republicans alike—were entirely unaware that this had occurred. Researchers polled citizens, asking if they knew whether the deficit had gone up or down under Clinton. As one might expect, the uninformed were just as likely to be right as to be wrong, with equal amounts saying it went up as said it went down. However, those with some political knowledge showed an interesting discrepancy. Among Democrats, those with some political knowledge were more or less in line with the completely ignorant. However, among Republicans, those with some information were far more likely to answer that the deficit had increased. Only in the 70th percentile of informed Democrats did respondents increasingly answer correctly that it had decreased. However, only in the highest percentile of informed Republicans were respondents slightly more likely to answer correctly that it had decreased. As Achen and Bartels summarize:

They knew that a Democrat was in office and that the president was in some way responsible for the deficit. …Thus a modicum of political information was enough for Republicans to figure out what ought to be true, but not to learn what was in fact true.[xxiv]

Again, what this means is that, even though partisans tend to be more informed than the completely ignorant members of the electorate, the partial amount of information they have only makes them more likely to be wrong. This is true for both parties, and affects beliefs about all manner of political realities, from relatively innocuous misconceptions about the budget deficit to more truly disturbing issues related to war and peace.

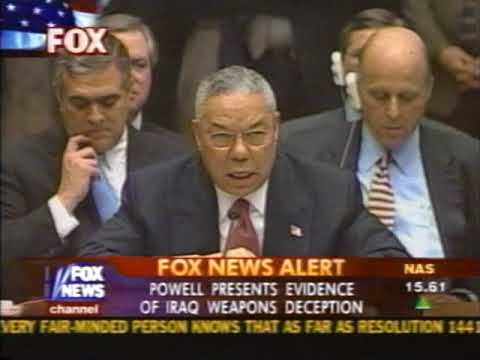

An example of the latter concerns partisan (mis)understanding about the threat posed by Iraq, even long after the US invasion:

More than 18 months after the 2003 U.S.-led invasion of Iraq, for example, 47% of Republicans (but only 9% of Democrats) said they believed that Iraq had possessed weapons of mass destruction on the eve of the invasion; 71% of Republicans (but only 37% of Democrats) believed that Iraq was directly involved in the 9/11 attacks or had provided substantial support to al-Qaeda.[xxv]

Of course, one can only wonder how much of this discrepancy owes to the aforementioned fragmentation of “news” sources into partisan propaganda channels. Those who never changed the channel from Fox after the runup to war would no doubt have been more misinformed about matters than those consuming different or more varied news. As it turns out, those who still have the dial there are no more likely to be disabused. According to a 2015 Public Mind poll from Fairleigh Dickinson University, 12 years after the invasion they were even more likely to be wrong:

more than half of Republicans — 51 percent — and half of those who watch Fox News — 52 percent — say that they believe it to be “definitely true” or “probably true” that American forces found an active weapons of mass destruction program in Iraq.[xxvi]

Such is the state of affairs in the US: an uninformed electorate getting more and more mis-informed as time goes by. Whether because of sheer ignorance, or because of irrational group identity politics, people are, as a whole, very bad at political engagement rooted in informed and reason-based decision-making.

So, what does this all amount to?

Jason Brennan provides some memorable analysis. Looking at the spectrum of political informedness, he catchily divides the electorate into three groups: hobbits, hooligans, and vulcans.

Hobbits are mostly apathetic and ignorant about politics. …In the United States, the typical nonvoter is a hobbit.

Hooligans are the rabid sports fans of politics. Hooligans consume political information, although in a biased way. They tend to seek out information that confirms their preexisting political opinions, but ignore, evade, and reject out of hand evidence that contradicts or disconfirms their preexisting opinions. …Their political opinions form part of their identity, and they are proud to be a member of their political team. …Most regular voters, active political participants, activists, registered party members, and politicians are hooligans.

Vulcans think scientifically and rationally about politics. Their opinions are strongly grounded in social science and philosophy. They are self-aware, and only as confident as the evidence allows.[xxvii]

Unfortunately, as citizens become more informed, they don’t leap from hobbit to vulcan. Rather, they become hooligans; vulcans are practically nonexistent. “Ignorance and apathy are the marks of the hobbit; bias and zealotry are the marks of the hooligan. …Americans are about divided, roughly in half, between hobbits and hooligans.”[xxviii] Such an analysis accords remarkably well with all that we have been discussing. They reinforce the picture we have been painting of an American electorate largely unprepared to handle the sort of complexity required by robust democratic engagement.

Such analysis may lead one to despair. Is democracy perhaps doomed to fail, you may ask? Is human ignorance and group-think so intractably a part of our nature that the very notion of collective governance is actually ridiculously naïve?

Studies like Asch’s conformity tests showed that a majority of people would shift their reality to match the group’s some of the time, 37% all of the time. But that means that some minority of people did resist the peer pressure to actually state with conviction the reality they experienced. Where does such autonomy come from?

Again, developmental models can shed some important light here. For they show that, after a period of early egocentric absorption, most people expand their horizons and come to form their sense of self through group identification as we’ve been discussing. Robert Kegan, for instance, has mapped this in studies on ego development, charting five “orders of consciousness” of increasing complexity. The first two are highly assimilatory and egocentric, while the 3rd order represents the socializing movement into a collectively-constituted identity. For much of human history, this highly conformist sort of self structure was entirely adaptive and healthy.

With the rise of modernity, however, a more complex social environment came to place a more demanding set of expectations on the individual: demands like thinking for oneself, standing up for your own individual values and principles, negotiating different perspectives in different contexts, and grappling more with the causal mechanisms of the world. These demands require a 4th order construction of self of higher complexity than the conformist one.

With the right supports and learning environment, this can indeed be achieved! Absent those, however, it is increasingly unlikely. That is why, today, only 1/3 of Americans are operating from this level of thought, and so very much “in over our heads” when it comes to navigating tendencies for group-think and conformism around tribal politics.

Around the world, democracies are under threat, and authoritarianism is on the rise. One major reason for this is the clear failures of democratic states to live up to their high ideals. In America, democracy seems stalled, stuck, broken. Congress persists in perpetual gridlock; systemic-level threats and existential risks go unattended to. The political poles supposed to help achieve higher dialectical synthesis have instead only become radicalized and pathological extremes increasingly alienated from any compromise with the other side. In such a situation, it is hard to blame one for beginning to question the validity or necessity of democratic governance—especially as geopolitical competitors like China and Russia pose alternative models of a more authoritarian bent which have avoided some of these impasses. Maybe, some think, we do just need some Strong Man to get the big things done?

If we wish to avoid this backsliding into regressive authoritarianism, democracies must become functional again and prove their progressive superiority in delivering on promises of freedom, security, and sustainable flourishing. Lacking an informed and knowledgeable electorate, however, this is impossible. What is needed is not “more education”; we have seen this. No, what is needed is better education. What is needed is a full, expansive, comprehensive, robust, resourced, and developmentally informed education system that is not just about quantity but quality. It is not an exaggeration to say that the future of America depends upon it. In fact, given America’s place of prominence and hegemony on the geopolitical stage, it is not an exaggeration to say that the future of the world depends on it.

More time and space would permit more reflection on what this might look like, but that’s beyond the scope of this piece. Here, I simply wanted to lay bare the the problem faced by our democracy as we head into the 2024 election. The bulk of this piece I drafted back in 2021, not long after the attack on the Capitol. Today, in 2024, the situation is little better, and in fact probably worse. Indeed, less than a week out from the election, it is essentially a coin toss whether Trump will win another term, showing just how deep and intractable the dynamics outlined here really are.

In my earlier draft, my assessment was more cynical and pessimistic. However, the more I have studied developmental theory and the promise of good pedagogy, the more optimistic I’ve become that change is indeed possible. Development is possible, together, collectively—if we can reform the core of our civilizational system: our schools. The difference between Kegan’s 3rd and 4th order consciousness is one order of hierarchical complexity (Lectical Level 10 vs. 11, respectively). With the right supports, we can help more students become the sort of independent thinkers our democracy requires, putting them on a better trajectory or “developmental curve” for success in the modern world.

That, however, is the topic for another day. For now, we can just say that, whatever the election outcome, good education and the future of democracy are inherently bound up with one another.[xxix] And if a better education is possible, then a free and open society is also possible. But to ensure this, we must not continue putting blind faith in a democratic system that is not grounded in an informed electorate. American democracy can work, but currently is not. And failing democracies tend to elect autocrats. For the future of democracy, then, we must tackle the complexity gap. If, as Kegan says, we are in over our heads, that means we have two options: we can either drown, or learn to swim.

Let’s keep learning.

NOTES

[i] Gustave Le Bon (1895) The Crowd (T. Fisher Unwin, London), 4.

[ii] Le Bon, The Crowd, 15-16.

[iii] Achen and Bartels, Democracy for Realists, 220.

[iv] Brennan, Against Democracy, 48.

[v] Achen and Bartels, Democracy for Realists, 220.

[vi] Achen and Bartels, Democracy for Realists, 228.

[vii] Achen and Bartels, Democracy for Realists, 234.

[viii] Achen and Bartels, Democracy for Realists, 266.

[ix] Achen and Bartels, Democracy for Realists, 268.

[x] Lazarfield PF, Berelson B, Gaudet H (1948) The People’s Choice: How the Voter Makes Up His Mind in a Presidential Campaign (Columbia University Press, New York); Berelson B, Lazarfield PF, McPhee WN (1954) Voting: A Study of Opinion Formation in a Presidential Campaign (University of Chicago Press, Chicago).

[xi] Achen and Bartels, Democracy for Realists, 222.

[xii] Achen and Bartels, Democracy for Realists, 223.

[xiii] Nichols, The Death of Expertise, 228.

[xiv] Brennan, Against Democracy, 40.

[xv] Nichols, The Death of Expertise, 69.

[xvi] Brennan, Against Democracy, 44.

[xvii] Le Bon, The Crowd, 32.

[xviii] Nichols, The Death of Expertise, 141.

[xix] Nichols, The Death of Expertise, 128-129.

[xx] Nichols, The Death of Expertise, 119.

[xxi] Nichols, The Death of Expertise, 120-121.

[xxii] Nichols, The Death of Expertise, 157.

[xxiii] Shani D (2006) Knowing your colors: Can knowledge correct for partisan bias in political perceptions? Presentation, Annual Meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association, Chicago.

[xxiv] Achen and Bartels, Democracy for Realists, 282-283.

[xxv] Achen and Bartels, Democracy for Realists, 277-278

[xxvi] Breitman K (2015) Poll: Half of Republicans still believe WMDs found in Iraq. Politico (January 7), https://www.politico.com/story/2015/01/poll-republicans-wmds-iraq-114016.

[xxvii] Brennan, Against Democracy, 4-5.

[xxviii] Brennan, Against Democracy, 24.

[xxix] Such was the working premise for our Education and the Future of Democracy symposium here at Sky Meadow back in February 2024 with Zak Stein and Lene Rachel Andersen.

Yes, quality education is essential for developing our collective awareness! Waldorf education, with its focus on educating the 'whole child,' may provide us with a blueprint.

I'm so glad to see such a in-depth discussion of Democracy for Realists. Over the past several years I've been amazed that the book didn't get more traction and dismayed that most political discussions in the press and elsewhere take for granted what Achen and Bartels have dubbed the "folk theory of democracy." Despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary, there is an uncritical acceptance of the idea that at the end of the day voters will more-or-less vote according to a somewhat reality-based agenda that reflects their own interests. One would hope that the 2024 political cycle could inspire some scepticism about the folk theory of democracy, but I'm not holding my breath...