America is in crisis. Calamities mount on every front as our institutions flounder. Increasingly, it seems, we do not appear capable of handling reality. Discourse devolves; the public arena is a circus. Debate degenerates to slogans bound to lies by half-truths and ad hominems. Fake news, “fake news,” speech codes, wokeness… Mobs and militias take to the streets, chanting their misconceptions; in the rallies: dittoheads hail demagogues, saluting spray-tanned television stars as statesmen. At last, the Capitol itself is stormed by throngs of deluded zealots, venting invented grievances contrived to rile the masses. What does it mean? What’s happening?

American democracy is supposed to be “government of the people, by the people, for the people.” But…what if the people don’t appear quite up to the job? A heretical thought, perhaps—but one reluctantly mulled more and more by anxious observers of American politics these days. The absurdities of the 2016 election cycle were finally enough to get some wondering it aloud. “Are Americans just stupid?” So Psychology Today and Canada’s National Observer both asked in identically-titled articles.[i] The sensible incredulous were desperate for answers.

For many, it was America voting the reality television celebrity Donald Trump into the highest office that shook their faith in the popular will. Even still, hope springs eternal; one could muster excuses for the anomaly. But four years later, 74 million Americans did it again—not enough to re-elect him, true, but only barely. The election was close. …It should not have been close. After 2020, it seems, there can be no arguing it anymore: something is broken at the very foundations of American democracy—a profound disconnect between factual realities and popular perceptions. The electorate is largely ignorant, misinformed, or both. More and more, a torturous idea is becoming more plausible: that We the People might simply be “in over our heads.”

That is the phrase Harvard developmental researcher Robert Kegan used for his 1994 book examining how well (or poorly) people in modern industrial countries were handling the complex demands of society placed on their cognitive abilities. Here, I’d like to extend this line of inquiry into the political domain. In this essay, I will explore some uncomfortable questions. Not, “Are Americans just stupid?” but, more charitably, are we simply “in over our heads?” Do we actually have the sort of informed citizenry needed for a functioning modern democracy? Or is there a mismatch between the complexity of our (geo)political moment and the level of political discourse we are actually capable of collectively engaging in? If so, is “more education” the answer? Or are more radical reforms needed?

Why does American politics look the way it does, and what does that bode for our democracy?

THE “UNINFORMED ELECTORATE”

There are some jobs that simply require expertise. One would be forgiven a pang of apprehension, for instance, if, about to go under the knife, one hears the doctor excuse himself for the restroom, handing the scalpel to the first person he sees on his way out the door with a “Good luck! You got this kiddo.” It is not snobbery that lies behind the resultant gulp of terror. Nor is elitist hubris responsible for what trepidation rises in the hearts of first and business class alike when a voice from the cockpit crackles from the loudspeaker, “Hi folks. Never flown one of these before, but your pilot’s out with a head cold. Shouldn’t be too hard. I played a pilot on TV once.”

The founders of the United States understood that the ship of state was not to be captained without a boater’s license. For a democracy to work, they all agreed, the people have to be informed. Thomas Jefferson wrote,

Wherever the people are well informed, they can be trusted with their own government.

Likewise, James Madison observed,

A popular Government, without popular information, or the means of acquiring it, is but a Prologue to a Farce or a Tragedy; or, perhaps, both. Knowledge will forever govern ignorance: And a people who mean to be their own Governors, must arm themselves with the power which knowledge gives.

Indeed, it’s generally understood that the first and most basic prerequisite for a well-functioning democracy is a well-informed citizenry.[ii] Unfortunately, the evidence—and there is a lot of it—reveals that the American electorate is far from well-informed.

In his 2016 book Democracy and Political Ignorance, Ilya Somin cites some sobering statistics. When it comes to the fundamentals, for instance: “A 2014 Annenberg Public Policy Center study found that only 36 percent of Americans could even name the three branches of the federal government: executive, legislative, and judicial. Some 35 percent could not name even one.”[iii] That means that only about 1/3 of Americans have the most basic grasp of the most basic structure of American democracy—another 1/3 are entirely ignorant of it. Meanwhile, “Majorities are ignorant of such basic aspects of the U.S. political system as who has the power to declare war, the respective functions of the three branches of government, and who controls monetary policy.”[iv]

In their book What Americans Know About Politics and Why It Matters, Michael X. Delli Carpini and Scott Keeter write this of their extensive analysis of survey findings:

[J]ust over half the questions about institutions and processes could not be answered by a majority of those asked. Included among the questions answered correctly by [only 1/4 to 1/2] of the public…are many items that seem critical to understanding politics in the United States. …Less than a majority can volunteer the percentage required for Congress to override a presidential veto, say how long a House member’s term is, or note that all congressional seats are contested at the same time every two years.[v]

All of this is laid out in the Constitution, of course—that (supposedly) most cherished and sacred of national documents. As it turns out, though, most Americans seem to have little knowledge of what it actually contains. According to Somin, only about 1/4 could name more than one of the rights enumerated in the Bill of Rights,[vi] while a 2003 Gallup poll showed that 1/2 of Americans don’t even know what the Bill of Rights is.[vii]

Unfortunately, the only thing worse than what people don’t know about the Constitution is what they think they know. Susan Jacoby cites surveys by the National Constitution Center which “show that 42 percent of Americans think that the Constitution explicitly states that ‘the first language of the United States is English’ and 1 in 4 believe that Christianity was established by the Constitution as the official government religion.”[viii] Somin cites a 2002 Columbia University study revealing that “35 percent believed that Karl Marx’s dictum ‘From each according to his ability to each according to his need’ is in the Constitution (34 percent said they did not know if it was or not).”[ix] Indeed, far from appreciating the significance of the separation of powers enshrined in the Constitution, surveys show that 1/6 Americans would accept a military dictatorship.[x]

Given such limited understanding of the rudiments of American government, it is not surprising to find similar ignorance when it comes to policy issues and the basic political realities of the day. Most Americans don’t even have a rough idea of what the federal budget is or what it’s spent on, who is taxed and at what levels, what the unemployment or poverty levels are, etc. Nor do they have a sense of who the main political players are: Most can’t name what party is in control of the House or Senate, who the Supreme Court Justice is, or who comprises the president’s cabinet.

When it comes to American history, the past fares even worse than the present: 1/3 of Americans don’t know who delivered the Gettysburg address; 40% don’t know who America fought in World War II; and 1/4 voters can’t say what country America gained its independence from.[xi]

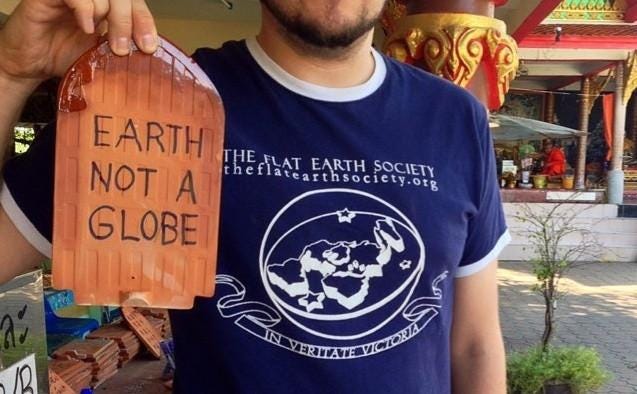

This civic ignorance is part of a broader trend in decreasing intellectual interest. Over 1/4 of Americans haven’t read one book, in whole or in part, in the last year.[xii] While this low level is due largely to apathy and unwillingness, it is also due to inability. According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, 1/2 of American adults can’t read a book written at an eighth-grade level; according to the U.S. Department of Education and the National Institute of Literacy, 32 million adults in the United States can’t read at all.[xiii] Given these sorts of statistics it becomes clearer how it is possible that 1/3 millennials think the Earth is flat[xiv] and 1/4 Americans actually believe the sun revolves around the Earth.[xv]

These are sobering statistics, but hopefully they offer some perspective. How can we have a meaningful debate, say, about the nature and potential limits of free speech, if every other American doesn’t grasp that we are talking about one of the freedoms enumerated in our Constitution? What does it mean to talk about the separation of church and state if 25% of Americans think Christianity is the state religion? If nothing else, such percentages should help to drastically rein in our assumptions about the scope and depth of what sort of political discourse is possible in America today.

Now, in shining a (glaring) light on this reality, I naturally open myself up to accusations of intellectual snobbery and pompous elitism. To this I can only say that, I assure you: I get no more pleasure from considering this reality than the above-mentioned patient on the operating table does when eyeing his newly-anointed surgeon, or the passengers on the tarmac do as they clutch the armrests in preparation for liftoff. In short, my objective is not to ridicule, scold, or deride my fellow Americans; even less is it to make myself or some other imagined band of haughty intellectuals look good by comparison. The point, simply, is to highlight the empirical discrepancy between the “informed citizen” we imagine as being necessary for a functional democracy and the reality of the electorate as it really is. Why our democracy has become so dysfunctional should hopefully become apparent as a consequence of recognizing this discrepancy.

And, unfortunately, such statistics are just the tip of the iceberg.

For even when the American electorate isn’t simply ignorant about basic matters of our government, they are undeniably confused about what they (think they) know. For instance, respondents to surveys about government policy consistently express self-contradictory opinions—such as wanting to reduce entitlements but also shore up Social Security; to cut taxes, but also decrease the deficit. A CNN poll from 2009 showed that while 71% of voters wanted smaller government, they also opposed cuts to Medicare (81%), Social Security (78%), and Medicaid (70%). Good luck deciphering the “will of the people” on that one.

As if all this were not problematic enough, researchers have also found that people’s professed views can change depending merely on the phrasing of the policy question they’re asked. In the mid-1980s, up to 65% of Americans said that the government was spending too little on “assistance to the poor,” but only 20% to 25% said it was spending too little on “welfare.”[xvi] In the lead-up to the 1991 Gulf War, almost 2/3 were willing to “use military force,” but fewer than 1/2 were willing to “engage in combat,” and fewer than 30% were willing to “go to war.”[xvii]

Clearly, something is at work here beyond simply asking people about their positions on different policy alternatives. Voters, it would seem, don’t so much support policies as slogans; not positions but talking points.

And yet, the reality remains: killing people in Baghdad will continue to be just that whether you call it “using military force,” “going to war,” or something else entirely.

Still, despite people’s ignorance about the issues, their self-contradiction in their stances, and their nonrational tendency to shift their support for a policy based on how it’s phrased, they will not be deterred from holding strong opinions nonetheless. As Tom Nichols, a professor of National Security Affairs at the U.S. Naval War College and author of The Death of Expertise: The Campaign Against Established Knowledge observes:

Polls upon polls show not only that Americans generally feel government spends too much…but also that they are consistently wrong about who pays taxes, how much they pay, and where the money goes. This, despite the fact that information about the budget of the United States is more accessible than the days when the government would have to mail a document the size of a cinder block to the few voters who wanted to see it.[xviii]

Indeed, all it takes is a quick Google Image search of “US budget” and one is immediately bombarded with pie graph after pie graph showing the specific allocations and percentages. Yet, despite this revolution in government transparency and the accessibility of information, it remains very easy for people to simply feel that, whatever the government is spending money on, it’s too much.

People’s attitudes to foreign aid is a good example of this sort of opinion-taking. “This is a hot-button issue among some Americans who deride foreign aid as wasted money,” writes Nichols.

Americans routinely believe, on average, that more than 25 percent of the national budget is given away as largesse in the form of foreign aid. In reality, that guess is not only wrong, but wildly wrong: foreign aid is a small fraction of the budget, less than three-quarters of 1 percent of the total expenditure of the Unites States of America. Only 5 percent of Americans know this. One in ten Americans, meanwhile, think that more than half of the US budget—that is, several trillion dollars—is given away annually to other countries.[xix]

That is, not knowing what the government spends money on doesn’t stop people from passionately denouncing government wasting vast amounts on foreign aid. In an intriguing instance of public delusion becoming policy, Donald Trump has played upon these popular-but-mistaken imaginings of vast, charitable waste by calling for a 21% reduction in foreign aid: huge bragging rights for a colossal windfall if that were indeed out of several trillion dollars and not the “less than three-quarters of 1 percent of the total expenditure of the Unites States.”

Of course, the dangers of electoral ignorance are nowhere better exemplified than in matters of war and peace—where our capacity to cause catastrophic suffering and humanitarian crisis is indeed very great. Given America’s unique role (for now) of chief military superpower and de facto custodian of the world order, the average US citizen occupies a profound level of power when it comes to determining the future of, well, whether people in other countries keep living. Just 537 votes separated a Bush presidency from a Gore presidency; exactly how many hundreds of thousands died from the invasion of Iraq will remain much murkier. If domestic concerns for our own 350 million fellow citizens were not enough, American global hegemony adds an additional solemn weight to the democratic burden of the electorate.

Unfortunately, like much else about our national affairs, this responsibility does not seem well grasped by voters. In fact, the ignorance of the uninformed electorate is, tragically, matched only by its knee-jerk openness to blow things up. Nichols observes:

only one in six Americans—and fewer than one in four college graduates—could identify Ukraine on a map. …Far more unsettling is that this lack of knowledge did not stop respondents from expressing fairly pointed views about [the issue]. Actually, this is an understatement: the public not only expressed strong views, but respondents actually showed enthusiasm for military intervention in Ukraine in direct proportion to their lack of knowledge about Ukraine.[xx]

Apparently, for some voters, lacking the most basic geographical literacy about a place—let alone a grasp of its complex role in broader geopolitical affairs—is only further justification for killing people there.

This disturbingly reckless sentiment was confirmed in the extreme by a poll taken by Public Policy Polling in 2015, which

asked both Republicans and Democrats whether they would support bombing the country of Agrabah. Nearly a third of Republican respondents said they would support such action. Only 13 percent were opposed, and the rest were unsure. Democrats were less inclined to military action: only 19 percent of self-identified Democrats supported bombing while 36 percent decisively voiced their opposition. Agrabah doesn’t exist. It’s the fictional country in the 1992 animated film Aladdin. …43 percent of Republicans and 55 percent of Democrats had an actual, defined view on bombing a place in a cartoon.[xxi]

Such results might be laughable, provided you don’t think too much about the implications. It is hard not to see how they reveal both the farce and the tragedy so feared by Madison.

Clearly, such levels of ignorance are not without very real consequences. In fact, as Jason Brennan notes, studies have shown that “poorly informed people have systematically different preferences from well-informed ones, even after correcting for the influence of demographic factors such as race, income, and gender.”[xxii] Specifically, “as people become less informed, they become more hawkish about intervention as well as in favor of protectionism, abortion restrictions, harsh penalties for crime, doing nothing to fix the debt, and so forth.”[xxiii] By contrast, more informed voters are more tolerant voters, less racist and less homophobic.[xxiv] There are, it simply seems, just not as many of them.

Somin observes that “the low level of political knowledge in the American electorate is still one of the best-established findings in social science.”[xxv] Social scientists Christopher Achen and Larry M. Bartels concur. In their book Democracy for Realists: Why Elections Do Not Produce Responsive Government, the Princeton and Vanderbilt University professors remark on the “substantial body of scholarly work demonstrating that most democratic citizens are uninterested in politics, poorly informed, and unwilling or unable to convey coherent policy preferences through ‘issue voting.’”[xxvi] Indeed, if one were to apply the standard academic grading system to what Americans know, the typical grade would be a D+.[xxvii] Actually, even that might be generous. As Brennan notes, polls and surveys actually “tend to overstate how much Americans know” by asking easy (usually multiple-choice) questions or yes/no questions without specificity about degrees or amounts. “They count a citizen as knowledgeable if they know that we spend more on social security than defense, but they typically don’t check if they know how much more we spend. …When voters don’t know degrees, they’re likely to misallocate resources and have the wrong priorities.”[xxviii]

Confronted with these dismal realities, most will be quick to grope for rebuttals or refutations. The validity of the fundamental presumption of American democracy would seem to have in the balance, after all—namely, that we collectively possess the requisite knowledge and capacity to govern ourselves (and, by extension owing to our geopolitical status, the world). If the electorate really is so uninformed, there must be some explanation that can still justify the idea of giving them the keys to the kingdom. Certainly, it will be said, something has gone very wrong along the way. It didn’t always use to be this bad. People used to be much more informed.

Unfortunately, a look at the numbers reveals that’s not quite the case. Public polling goes all the way back to the 1930s, offering us almost a century of data. While this is a substantial period of time to assess, it is also, perhaps, surprising to consider that, before the mid-twentieth century, politicians and political theorists were basically flying blind when it came to the “will of the people.” The advent of polling was heralded as a boon for democracy, as a way to take the temperature of the electorate. However, it also revealed for the first time the true scale of the public’s ignorance.

Following back the polls to the early twentieth century, we find the same story as that above, no matter the decade. Delli Carpini and Keeter relate some representative findings:

In 1986, only 49% knew which one nation in the world had used nuclear weapons

In 1972, only 22% knew something about Watergate

In 1952, only 44% could name at least one branch of government

In 1943, only 6 percent of incoming college freshmen could list the original thirteen colonies.[xxix]

Summarizing their findings, Delli Carpini and Keeter write:

Drawing on several hundred knowledge questions that have been asked more than once over the past half century, we conclude that the public’s level of political knowledge is little different today than it was fifty years ago. Given the ample reasons to expect changing levels of knowledge over the past fifty years, this finding provides the strongest evidence for the intractability of political knowledge and ignorance.[xxx]

Their work confirms similar findings by Russell Neuman, Stephen Bennett, and Eric Smith, “which suggest that knowledge is at best no greater than it was two to four decades ago.”[xxxi] Achen and Bartels express the exasperation of the consensus when they write, “[I]t is striking how little seems to have changed in the decades since survey research began to shed systematic light on the nature of public opinion.”[xxxii] In short, the general electorate was not much more informed in the past. Things have always been, well, pretty bad.

Well, it will be said, all the more need for more education! The solution for ignorance is always more education. The problem here is not enough education and access to information.

This sounds promising at first. After all, the best predictor of political sophistication is education level. Unfortunately, the idea that “more education means more informed citizens” is simply not borne out by the data either. In 1950, approximately 50% of the population over the age of 25 had completed high school and 5% of the population had completed college; today, over 90% have completed high school and the percentage of college graduates is nearing 40%. Still, despite these dramatic increases in educational attainment, political ignorance has remained virtually unchanged.

In his book The Unchanging American Voter, Eric Smith found that students’ levels of factual political knowledge do not greatly increase as they progress through high school and college. “[E]ducation,” he concludes, “is not the key to the public’s understanding of politics.”[xxxiii] In fact, the increase in education has, in practice, actually served to make higher levels of education less important today. The effect of people’s stampede into universities has not been so much the raising of their level of informedness as an overall debasing of the quality of education—making today’s college graduates less competent compared to their equivalents in 1950. Simply put, our typical public education efforts have done surprisingly little to change the levels of the electorate’s civic ignorance. And as for access to information, the internet has made that more universally available than ever before. It is clearly not a lack of access but a lack of understanding that afflicts us.

In short, information is of little use if people do not seek or understand it, while formal education is little better if it fails to actually properly educate people.

In each instance, what we are actually concerned to track by such variables, of course, isn’t just how many years someone went to a building with the word “school” on it, but the cognitive capacities that are supposed to be developed there for people to be able to better make informed, reasonable decisions based on evidence. To measure cognitive ability is to tap a deeper construct which, clearly, is only loosely correlated with superficial metrics like how much formal schooling one has had.

On this point, Robert Luskin is insightful. As noted above, education level remains the best predictor of political informedness—yet more education has not produced more informed citizens. Why? “The simplest explanation,” says Luskin, “is the paucity of controls.” That is, one must ask: What is really being captured in the “education” variable?

Education, defined as years of schooling, is easy to measure. …But to what degree are education’s effects really education’s? Does education affect participation, or is the effect really sophistication’s or (one step back) intelligence’s? Arguments for education effects are often really arguments of intelligence, interest, sophistication, or occupation effects. It is time to unconfound these variables.[xxxiv]

This is precisely what Luskin’s analysis does, and finds that intelligence is “quite important” while mere education level is actually “unimportant.”[xxxv] “Education probably has some effect outside the model,” Luskin presumes, “but mostly through ability (intelligence), not the dissemination of political information.”[xxxvi] As the old adage goes, correlation is not causation. Education level is correlated with political informedness, but intelligence is also correlated with education level. Disentangling them reveals that the persistent finding of political scientists that the more educated are the more informed citizens means that the more intelligent, who attain higher levels of education, are more informed citizens, not that getting any old education will necessarily make you one. Later research seems to confirm Luskin’s findings. Delli Carpini and Keeter note:

Large-scale experimental research by Neuman, Just, and Crigler (1992: 97) concluded that cognitive ability was one of the two strongest predictors of baseline levels of [political] knowledge… In this multivariate analysis, education level was a much weaker predictor…[xxxvii]

One historically popular construct for measuring cognitive ability has been IQ (or “intelligence quotient”). And, indeed, using this metric, studies have in fact shown links between a person’s IQ and their political sophistication—a correlation more important, in fact, than educational attainment, socioeconomic status, or other oft-cited environmental elements.

In one study from the 1960s, for instance, some 12,000 students (grades 2 through 8) were asked how much they understood the workings of government and how much they read or talked about politics with friends or family, etc. The results are summarized by Richard J. Herrnstein and Charles Murray:

The big surprise in the study was the impact of IQ, which was larger than that of socioeconomic status. Brighter children from even the poorest households and with uneducated parents learned rapidly about politics, about how the government works, and about the possibilities for change. They were more likely to discuss, read about, and participate in political activities than intellectually slower children.[xxxviii]

A 1970 study of approximately 400 high school students[xxxix] showed similar results for adolescents:

The survey questions tapped a wide range of political behaviors and attitudes. From the responses, scales were constructed for fourteen political dimensions. …To a remarkable degree and with only a few exceptions, each of the political dimensions was most strongly correlated with intelligence.[xl]

Such is the data from IQ studies. However, I would stress that IQ is only one metric—and actually a very problematic one.[xliv] By contrast, the field of cognitive developmental psychology has produced far more valid constructs for assessing cognitive ability, such as hierarchical complexity.[xlv] Unlike IQ, this construct is based in solid developmental theory, not just statistical analysis. Importantly, moreover, it does not make strong claims about heritability the way proponents of IQ do (often to highly problematic implications), but rather focuses much more on the ideal environmental supports and contexts for real, robust learning to occur. Indeed, given such supports, developmental models tend to evidence the capacity for “upward mobility” in terms of cognitive capacity and resultant socioeconomic status. What matters is not one’s genes but one’s learning environment and resources.[xlvi]

The work of researchers like Kurt Fischer, Theo Dawson, and Zak Stein have shown that, when it comes to improving the cognitive abilities of people, the question is not about more education but what sort of education is offered. And, simply stated, America is failing its students (of all ages) when it comes to fostering real, robust, deep learning through the kind of education that actually matters.

Unfortunately, there have been no major studies to date that I am aware of which study correlations between popular political behavior and cognitive ability in terms of hierarchical complexity. There are, however, obvious parallels between patterns in increasing development and the policy positions taken by increasingly informed voters. Developmental research across multiple domains repeatedly reveals a general progression from simplistic, absolutistic, and egocentric/ethnocentric thought to more nuanced, relativistic, and pluralistic thought. This insight dovetails well with findings, cited earlier, showing that “as people become less informed, they become more hawkish about intervention as well as in favor of protectionism, abortion restrictions, harsh penalties for crime, doing nothing to fix the debt, and so forth,” while more informed voters are more tolerant voters, less racist and less homophobic. Could the breakdown of American democracy be a question less about media, technology, or even economic trends, and more about human learning and development?

As noted above, Harvard developmental researcher Robert Kegan famously argued that the majority of Americans today are “in over their heads” when it comes to meeting the cognitive challenges of the “hidden curriculum” of modern and postmodern life. His research suggests that only 34% of the population employs the requisite cognitive complexity to properly meet the demands of modern life. That would suggest that 2/3 of the electorate are in over their heads when it comes to adequately assessing political information and making the sort of informed decisions necessary for a complex modern democracy. Indeed, when it comes to the sort of postmodern thought such as we see contributing to culture war debates around issues like the social construction of gender, critiques of neoliberal capitalism, and systems-based ecological analysis, that number falls to only 1%!

These are grim figures indeed. But cognitive capacity, it turns out, is only half the battle. Americans’ cognitive abilities alone are simply not enough to account for the levels of confusion, error, and misguidedness so prevalent among the electorate. There is another factor—one equally ingrained in our nature, but far more dangerous—which continues to thwart the prospect of a genuinely informed and rational citizenry. That issue we will tackle next.

NEXT:

Political Conformity & the Developmental Constraints on Democracy

Human beings are social animals. It is in our nature to form groups and to see our group membership as critical to our identities as individuals. (Indeed, this is actually a key part of the developmental process.) Unfortunately, though, this form of socialization can come with a severe tradeoff: the

NOTES

[i] David Niose (2016) Are Americans just stupid? Psychology Today (October 4), https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/our-humanity-naturally/202010/are-americans-just-stupid; Livesay B (2017) Are Americans just stupid? Canada’s National Observer (November 15), https://www.nationalobserver.com/2017/11/15/opinion/are-americans-just-stupid.

[ii] See Richard D. Brown (1996) The Strength of a People: The Idea of an Informed Citizenry in America, 1650-1870 (The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, NC).

[iii] Somin Ilya (2016) Democracy and Political Ignorance (Stanford University Press, Stanford, CA), 20.

[iv] Somin, Democracy and Political Ignorance, 20.

[v] Michael X. Delli Carpini and Scott Keeter S (1996) What Americans Know About Politics and Why It Matters (Yale University Press, New Haven), 72.

[vi] Somin, Democracy and Political Ignorance, 20.

[vii] George Gallup (2003) How many Americans know U.S. History? Part I. Gallup.com (October 21), https://news.gallup.com/poll/9526/how-many-americans-know-us-history-part.aspx.

[viii] Susan Jacoby (2018) The Age of American Unreason in a Culture of Lies (Vintage Books, New York), 313.

[ix] Somin, Democracy and Political Ignorance, 20.

[x] Roberto Stefan Foa, Yascha Mounk (2016) “The democratic disconnect.” Journal of Democracy 27(3):12-13.

[xi] George Gallup (2003) How many Americans know U.S. History? Part I. Gallup.com (October 21), https://news.gallup.com/poll/9526/how-many-americans-know-us-history-part.aspx; Zogby Analytics, poll, July 21-27, 2006; Crabtree S (1999) New poll gauges Americans’ general knowledge levels. Gallup.com (July 6), https://news.gallup.com/poll/3742/new-poll-gauges-americans-general-knowledge-levels.aspx.

[xii] Andrew Perrin (2019) Who doesn’t read books in America? Pew Research Center (September 26), https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/09/26/who-doesnt-read-books-in-america/. In 2002, less than half of adult Americans reported reading a single work of fiction or poetry in the proceeding year; only 57% had read at least one nonfiction book; Susan Jacoby (2018) The Age of American Unreason in a Culture of Lies (Vintage Books, New York), xxv.

[xiii] Valerie Strauss (2016) “Hiding in plain sight: The adult literacy crisis.” The Washington Post (November 1, 2016).

[xiv] Trevor Nace (2018) Only two-thirds of American millennials believe the earth is round. Forbes (April 4), https://www.forbes.com/sites/trevornace/2018/04/04/only-two-thirds-of-american-millennials-believe-the-earth-is-round/.

[xv] Scott Neuman (2014) 1 in 4 Americans thinks the sun goes around the Earth, survey says. NPR (February 14), https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2014/02/14/277058739/1-in-4-americans-think-the-sun-goes-around-the-earth-survey-says.

[xvi] Ken A. Rasinski (1989) “The Effects of Question Wording on Public Support for Government Spending.” Public Opinion Quarterly 53, 391.

[xvii] John Mueller (1994) Policy and Opinion in the Gulf War (University of Chicago Press, Chicago), 30.

[xviii] Tom Nichols (2017) The Death of Expertise: The Campaign Against Established Knowledge (Oxford University Press, New York), 27.

[xix] Nichols, The Death of Expertise, 27.

[xx] Nichols, The Death of Expertise, 2; emphasis original.

[xxi] Nichols, The Death of Expertise, 229.

[xxii] Jason Brennan (2017) Against Democracy (Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ), 34.

[xxiii] Brennan, Against Democracy, 34.

[xxiv] Delli Carpini and Keeter, What Americans Know About Politics and Why It Matters, 221ff, 248ff.

[xxv] Somin, Democracy and Political Ignorance, 19.

[xxvi] Christopher H. Achen, Larry Bartels (2016) Democracy for Realists: Why Elections Do Not Produce Responsive Government (Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ), 14.

[xxvii] Stephen Earl Bennett (1988) “Know-nothings revisted: The meaning of political ignorance today.” Social Science Quarterly 69:476-490.

[xxviii] Brennan, Against Democracy, 27-28.

[xxix] Delli Carpini and Keeter, What Americans Know About Politics and Why It Matters, 70, 81, 74, 84; adapted.

[xxx] Delli Carpini and Keeter, What Americans Know About Politics and Why It Matters, 17; emphasis added.

[xxxi] Delli Carpini and Keeter, What Americans Know About Politics and Why It Matters, 116.

[xxxii] Achen and Bartels, Democracy for Realists, 37; emphasis added.

[xxxiii] Eric Smith (1989) The Unchanging American Voter (University of California Press, Berkeley), 219.

[xxxiv] Robert Luskin (1990) “Explaining political sophistication.” Political Behavior 12(4):350.

[xxxv] Luskin, “Explaining political sophistication,” 347.

[xxxvi] Luskin, “Explaining political sophistication,” 351.

[xxxvii] Delli Carpini and Keeter, What Americans Know About Politics and Why It Matters, 195-196.

[xxxviii] Richard Herrnstein, Charles A. Murray (1994) The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life (The Free Press, New York), 256.

[xxxix] S.K. Harvey, T. G. Harvey (1970) Adolescent political outlook: The effects of intelligence as an independent variable. Midwest J. Political Science 14:565-595.

[xl] Herrnstein and Murray, The Bell Curve, 257.

[xli] Reproduced from Table 4.6 of Delli Carpini and Keeter, What Americans Know About Politics and Why It Matters, 153.

[xlii] Delli Carpini and Keeter, What Americans Know About Politics and Why It Matters, 154.

[xliii] Achen and Bartels, Democracy for Realists, 216.

[xliv] See, for instance, the critique of developmental theorist Zak Stein (e.g., Chapters 2 and 3 in Education in a Time Between Worlds: Essays on the Future of Schools, Technology, and Society (Bright Alliance, 2019)).

[xlv] See Sergio Morra et al., Cognitive Development: Neo-Piagetian Perspectives (New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2008); cf. Robbie Case, Intellectual Development: Birth to Adulthood (Orlando: Academic Press, 1985); The Mind’s Staircase: Exploring the Conceptual Underpinnings of Children’s Thought and Knowledge (Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1991); L. Todd Rose and Kurt W. Fischer, “Dynamic Development: A Neo-Piagetian Approach,” in The Cambridge Companion to Piaget, eds. Ulrich Müller, Jeremy I. M. Carpendale, and Leslie Smith (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 400–421; Michael L. Commons and Shuling Julie Chen, “Advances in the Model of Hierarchical Complexity (MHC),” Behavioral Development Bulletin 19 (2014), 37–50; Sagun Giri, Michael L. Commons, William Harrigan, “There is Only One Stage Domain,” Behavioral Development Bulletin 19 (2014), 51–61. Theo Dawson and Sonya Gabrielian, “Developing Conceptions of Authority and Contract across the Life-Span: Two Perspectives,” Developmental Review 23 (2003), 162–218.

[xlvi] This is a much more optimistic picture than that painted by IQ sociologists like Charles Murray, whose book The Bell Curve too easily falls prey to racist conclusions when genetic inheritance is identified as the chief factor accounting for differences in intelligence among different demographics. We can and should assign such simplistic notions to the trash heap of history. Moving beyond IQ towards more holistic models of development are key for this.

I agree with your main points- we have to revamp education to meet the complexity of the moment. I wrote a summary of a book making the same general point- our interior complexity must match the exterior one, else things fall apart- https://adamkaraoguz.substack.com/p/book-summary-the-watchmans-rattle. There is much more than "education" or "knowledge of the constitution" going on with voting preferences, though. It's not that simple, which I assume you will go into in your next piece.

Thank you, Brendan. I was hoping someone like you would outline this problem of complexity with accuracy and compassion. Looking forward to the next installment!