Origins of Metamodernism, Part II

The Birth of Metamodern Discourse in Cultural Studies

Oscillation, Metaxy, and the Donkey-Carrot Double-Bind

Vermeulen and van den Akker’s essay “Notes on Metamodernism” appeared in the Journal of Aesthetics and Culture in 2010 and represents the genesis of cultural studies metamodernism proper.[i] From 2009 to 2016, Vermeulen and van den Akker then co-edited an online webzine of the same name, publishing submissions on the topic from academics, researchers, artists, and critics.[ii] In 2017, joined by Alison Gibbons, they published their book: an anthology of essays by various authors titled Metamodernism: Historicity, Affect and Depth after Postmodernism. Such works have been pivotal in establishing a line of research into post-postmodern aesthetics by honing a powerful new rubric for analyzing contemporary art and cultural movements that no longer conform to the old familiar postmodern forms.

My own engagement with metamodernism dates to this time. Discovering Vermeulen and van den Akker’s 2010 essay not long after it was published, I was immediately taken by their articulation of the emerging zeitgeist. By 2013, I was curating a website on metamodern art and, in 2014, was invited to present a paper at the first academic conference on metamodernism at the University of Strathclyde (published that year in Notes on Metamodernism as “[Re]construction: Metamodern ‘Transcendence’ and the Return of Myth’).[iii] It was in Glasgow that I first directly connected with Vermeulen, Gibbons, and a number of other budding metamodern scholars, followed two weeks later in Amsterdam by the Stedelijk’s Metamodernism: The Return of History event (where I even ran around the museum with Shia LaBeouf as part of his metamodern performance art piece #METAMARATHON). My work on metamodernism thus dates back over a decade now, and I have been able to track—and sometimes, in a very modest way, help shape—the evolution of the discourse almost since its inception, which aids this present attempt to chart and synthesize its various currents and offshoots.

Vermeulen and van den Akker posed their formulation of metamodernism as an intervention into the debate about postmodernism’s successor, as cultural critics had for some time both noted postmodernism’s decline[iv] and some had even attempted to theorize the new form that modernity had taken (to limited success).[v] Drawing on the insights of theorists who traced postmodernism’s critical response to the modern, Vermeulen and van den Akker succeeded where others failed by identifying an important transformation of typically modern and postmodern dynamics into the metamodern.

To see this, it’s important to appreciate how the postmodern plays the yin to the modern’s yang, so to speak. That is, what all the theories of the “postmodern” had in common was an antithetical stance to “the modern.” As Vermeulen and van den Akker put it:

[T]he initial heralds of postmodernity, broadly considered to be Charles Jencks, Jean-Francois Lyotard, Fredric Jameson, and Ihab Hassan, each analyzed a different cultural phenomenon—respectively, a transformation in our material landscape; a distrust and the consequent desertion of metanarratives; the emergence of late capitalism, the fading of historicism, and the waning of affect; and a new regime in the arts. However, what these distinct phenomena share is an opposition to “the” modern—to utopism, to (linear) progress, to grand narratives, to Reason, to functionalism and formal purism, and so on. These positions can most appropriately be summarized, perhaps, by Jos de Mul’s distinction between postmodern irony (encompassing nihilism, sarcasm, and the distrust and deconstruction of grand narratives, the singular and the truth) and modern enthusiasm (encompassing everything from utopism to the unconditional belief in Reason).[vi]

Thus, following de Mul, modernism and postmodernism represent a sort of dipolar opposition, with postmodernism in the role of modernity’s evil twin. Hassan, for instance, famously depicted this opposition in an oft-cited table[vii] contrasting the two (abridged below):

Adopting this oppositional polarity of modern and postmodern, Vermeulen and van den Akker posit the metamodern as achieving a productive “oscillation” between these poles. The essence of emergent post-postmodern culture can be understood, then, as a continual movement between these nodes. As they put it:

Ontologically, metamodernism oscillates between the modern and the postmodern. It oscillates between a modern enthusiasm and a postmodern irony, between hope and melancholy, between naïveté and knowingness, empathy and apathy, unity and plurality, totality and fragmentation, purity and ambiguity. Indeed, by oscillating to and fro or back and forth, the metamodern negotiates between the modern and the postmodern.[viii]

It is precisely to capture this oscillation that they employed the prefix meta for its numerous etymological meanings. As they explain:

According to the Greek-English Lexicon the prefix “meta” refers to such notions as “with”, “between”, and “beyond”. We will use these connotations of “meta” in a similar, yet not indiscriminate fashion. For we contend that metamodernism should be situated epistemologically with (post) modernism, ontologically between (post) modernism, and historically beyond (post) modernism.[ix]

Metamodernism is thus a novel sort of third thing that arises out of the oscillation between modernism and postmodernism. That is, the distinctly metamodern art emerging in the 2000s exhibited aspects of both modernism and postmodernism, yet, despite being “made up” from these two poles, also transcends them because, in the end, it is really neither of them. They write:

Both the metamodern epistemology (as if) and its ontology (between) should thus be conceived of as a “both-neither” dynamic. They are each at once modern and postmodern and neither of them.[x]

Because it cannot be reduced to either its modern or postmodern nodes, metamodernism emerges as a distinct, novel logic offering entirely new kinds of cultural products owing to this uniqueness. It is a new kind of between (meta), a creative product of a prior polarity.

That said, the language of “polarity” suggests a simpler sort of dichotomy than Vermeulen and van den Akker have in mind. The dynamics are not in fact binary, but multiple. They caution:

One should be careful not to think of this oscillation as a balance however; rather, it is a pendulum swinging between 2, 3, 5, 10, innumerable poles.[xi]

These represent the various “residual” and “emergent” cultural logics, still extant, with which the dominant metamodern perspective contends.[xii] Again, as they make clearer in their 2017 explication, this is part of the meaning of meta in metamodern: the being with or among older cultural logics no longer dominant:

First, the metamodern structure of feeling is situated with or among older and newer structures of feeling. As indicated, this first and foremost entails that metamodernism is today’s dominant structure of feeling among a host of subordinate structures of feeling that Williams dubbed residuals and emergents.[xiii]

All of this supports my idea of metamodernism as a cultural logic of cultural logics. The metamodern navigates and negotiates not just the modern and postmodern, but a plurality of sensibilities and structures. What Vermeulen and van den Akker call “oscillation,” I call “toggling,” since this better captures that sense of plurality. Whereas the former suggests a “back and forth” polarity, the latter indicates an ability to jump in and out of multiple different frames. In sum, we oversimplify metamodernism if we reduce it to a simple fluctuation between the modern and the postmodern. While there may indeed be a “predilection” (as they put it) for the modern as the primary other pole, multiple other “residual” cultural logics exist—other perspectives that counter the postmodern one, holding it in check and complexifying it.

Appreciating this is important, I think, for a full understanding of metamodernism’s distinct sensibility—one of the most insightful aspects of Vermeulen and van den Akker’s analysis. By “sensibility” or “structure of feeling,” they mean something like the unique “vibe” or “tone” or “air” of metamodern works. This is that certain feel, the je ne sais quoi, that is everywhere pervasive in a period’s cultural production but nowhere tangible.[xiv] The phrases they coin to capture metamodernism’s sensibility are spot-on and get to the essence of so many metamodern works of art. “Informed naiveté,” “pragmatic idealism,” and, most notably, “ironic sincerity” are all named as characteristic of this new structure of feeling—seeming paradoxes that become sensible in the context of an oscillation between “modern enthusiasm” and “postmodern irony.”

These represent a sort of coniunctio oppositorum (union of opposites) which might seem like pure abstractions until you see them at work in real artistic productions. To offer my own list, “informed naiveté” is a perfect description for the saccharine yet self-aware innocence of Wes Andersen’s Moonrise Kingdom (2012), for instance, the good-natured humor of Ted Lasso, or the works of Miranda July. “Pragmatic idealism” captures the unique sort of motivational commitments driving characters in Life of Pi (2012) and The Lego Movie (2014). “Ironic sincerity” hits the nail on the head to describe the vibe of films as diverse as I Heart Huckabees (2004), The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou (2004), Little Miss Sunshine (2006), Birdman (2015), and The Unbearable Weight of Massive Talent (2022). Such works somehow manage to speak to a very uncynical, wholesome side of us, touching themes such as love, friendship, family, gratitude, redemption, etc., without forfeiting the very ironic or satirical attitude we’ve come to associate with fresh, bold, witty postmodern art.

Now, if the term “modern” really represented the essence of hope, naiveté, earnestness and aspiration the way Vermeulen and van den Akker’s framing suggests (following de Mul), then its polar oscillation with postmodern irony and cynicism would indeed explain such lovely contradictions. However, I must note, this is hardly the case—as even a moment’s reflection on modernity and modern culture makes immediately obvious. Isn’t the modern cultural logic also the wellspring of skeptical science? The disenchantment of magic and unreflective belief? Sure, relative to the postmodern, the modern may represent (as in Hassan’s chart above) “Purpose,” “Hierarchy,” “Metaphysics,” etc. But relative to earlier premodern traditionalism, the modern rings as comparatively purposeless (e.g., scientific reductionism, mechanism, blind evolution), anti-hierarchical (e.g., abolishment of nobility, loss of the Great Chain of Being, meritocracy), and anti-metaphysical (e.g., naturalism, physicalism). That is, relative to the cultural logic that came before it, the modern is not naïve at all, but informed; not idealistic, but realistic.

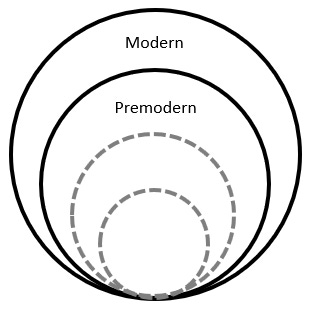

This doesn’t mean Vermeulen and van den Akker are wrong, just that their “modern” is doing more work than it seems, concealing deeper levels of recursive reflection within a single label. It is serving as a stand-in, essentially, for all that constitutes the “pre-postmodern”—which is to say, every logic that is less reflective than the postmodern.

One way to express this is that their use of the “modern” contains within it the other, earlier logics that it superseded.

Another way to make the point is simply to adopt their notion of a polarity, but to clarify what the poles really are: not the modern and postmodern per se, but the entire spectrum of increasingly reflective cultural logics:

As a cultural logic itself, the metamodern is with (meta) all of these residual cultural logics, toggling between them as it oscillates between (meta) these poles.

It is understandable why Vermeulen and van den Akker, seeking to theorize the post-postmodern, do not go so far with their analysis, as they are trying to narrow their focus to an analysis of fairly contemporary cultural change. To have to consider sensibilities as far back as the premodern may seem like overkill, then, but it is in fact necessary if we are to fully appreciate the dynamics at work here. The informed naiveté behind the metamodern play with, for instance, belief in prophecies (The Lego Movie), ancient mysticism (Dr. Strange), or witchcraft (The Witch) certainly does not owe to any kind of oscillation back to the “modern.” These are all premodern sensibilities that are being nested within a postmodern awareness.

In this way, metamodernism’s engagement with the “modern” can itself be decomposed into other poles (as Vermeulen and van den Akker themselves acknowledge), giving us a better sense of the dynamics in play. The generative oscillation is not between the modern and postmodern, but between logics with a higher or lower degree of recursive reflection. This is the spectrum that the metamodern inhabits, pulled between the unreflective immediacy of naiveté, earnestness, and what David Foster Wallace called “single-entendre principles” and the reflective awareness of knowingness, irony, and ambiguity.

To capture this idea of the meta as being between cultural logics, Vermeulen and van den Akker draw upon Eric Voegelin’s use of the Greek concept of metaxis, a term capturing the perennial condition of existence between two poles: namely, the finite and the infinite. As the human condition exists between these poles, so the metamodern condition, they say, is one between (pre)modernity’s teleological hopes and postmodernity’s skepticism toward all Absolutes:

As one critic puts it: metaxis is “constituted by the tension, nay, by the irreconcilability of man’s participatory existence between finite processes on the one hand, and an unlimited, intracosmic or transmundane reality on the other”… The metamodern is constituted by the tension, no, the double-bind, of a modern desire for sens and a postmodern doubt about the sense of it all.[xv]

Before postmodernism, the aspirational idealism of grand narratives had a telos, or goal. Premodern narratives focused on supernatural transcendence like salvation to Heaven or release from samsara. Modern narratives immanentized the eschaton or telos as the striving towards Utopia. Progress placed humanity on a trajectory to achieve ultimate fulfillment, ultimate satisfaction, ultimate truth. The Enlightenment promised a single correct answer for every question; Hegel’s vision promised a culmination of Spirit in Absolute Knowledge; Marx preached the apogee of a totally classless society, etc. All were final, pinnacle realities—the totalizing end of the teleological quest.

Postmodern thought utterly undermined such notions. There was no absolute Truth, said the postmodern critics, only a plurality of perspectives and micronarratives; an infinitude of different possible ends and goals, a myriad of different ways to represent reality and orient oneself within it. As such, who could say what was right? Why affirm any truth over another? Why commit to any ideals at all? Postmodernism eschewed any telos. The world wasn’t going anywhere, at all, and fast.

Terry Eagleton captured this sentiment with anti-totalitarian flare in a 1987 piece entitled ‘Awakening from Modernity,’ writing:

Post-modernism signals the death of such ‘metanarratives’ whose secretly terroristic function was to ground and legitimate the illusion of a ‘universal’ human history. We are now in the process of wakening from the nightmare of modernity, with its manipulative reason and fetish of the totality, into the laid-back pluralism of the post-modern, that heterogeneous range of life-styles and language games which has renounced the nostalgic urge to totalize and legitimate itself… Science and philosophy must jettison their grandiose metaphysical claims and view themselves more modestly as just another set of narratives.[xvi]

By contrast, metamodernism (argue Vermeulen and van den Akker) re-envisions the basic notion of progress, embracing both the aspirational journey of the modernists and the infinite plurality of the postmodernists. Metamodern progress, they suggest, is a playful dance towards an infinitely receding goal, the endless end, the telos of infinity:

That is to say, humankind, a people, are not really going toward a natural but unknown goal, but they pretend they do so that they progress morally as well as politically. Metamodernism moves for the sake of moving, attempts in spite of its inevitable failure; it seeks forever for a truth that it never expects to find. If you will forgive us for the banality of the metaphor for a moment, the metamodern thus willfully adopts a kind of donkey-and-carrot double-bind. Like a donkey it chases a carrot that it never manages to eat because the carrot is always just beyond its reach. But precisely because it never manages to eat the carrot, it never ends its chase, setting foot in moral realms the modern donkey (having eaten its carrot elsewhere) will never encounter, entering political domains the postmodern donkey (having abandoned the chase) will never come across.[xvii]

In this way, one achieves genuine progress—through inevitable failure. But each “failure” is really a gain, since it keeps the entire journey going. These gains are not mere illusions but represent real moral and political progress. They are only failures relative to some Absolute—some perfect, final end. The metamodern eschews the modernist Absolute. Their goal is an infinitely receding horizon. Their Absolute is never a stasis of Being but always in the process of Becoming.

Such notions match precisely to what I call the infinitesimal progress of eternal recursion. Metamodernism reconstructs notions of development and advance out of postmodern notions of relativity. All progress is relative, the metamodernist can say, pleasing both moderns (by affirming the reality of progress) and postmoderns (by affirming its lack of an Absolute goal). In this way, metamodernism reclaims the narrative thread lost in postmodernism. It “moves for the sake of moving,” for the journey not the destination, traversing Jacob’s ladder, and in the process trailblazes to new provisional destinations on the way, leading to “progress morally as well as politically.”

New Depths and Performing Transcendence

A similar idea shines through in Vermeulen’s articulation of metamodern intimations of depth. Whereas Jameson had equated postmodernism with a “new depthlessness” in the arts—one that abandoned notions of there being any “deeper” meaning to texts in favor of shallowly embracing the superficial as the new totality—Vermeulen sees in metamodern art new ways of actively re-engaging depth. “In philosophy and art alike,” he writes in a 2015 e-flux article, “notions of the behind and the beyond, the beneath and the inside, have reemerged.”[xviii] This “new ‘depthiness’” is not the old depth of modernist interpretations, but neither is it the flittering surface attention of postmodernists. Instead, the metamodern performatively draws depth out of surface in “an approximation of depth which acknowledges that the surface may well be depthless, while simultaneously suggesting an outside of it nonetheless.”[xix]

This is a “simulated” depth, wherein simulation is no longer the hollow pretense of life in The Truman Show (1998) or the flat code of The Matrix (1999), but actually the locus for a new kind of dimensionality altogether (perhaps, even a “deeper” kind of depth?). Recognizing the postmodern obsession with simulation and simulacra, Vermeulen notes: “Many contemporary artists, however, re-territorialize these languages of simulation to suggest not the final stage in a history of depthlessness but the first one in another chronicle of depthiness.”[xx] Specifically, if the old modernists were like ocean divers plunging down into the hidden depths for treasure, and the postmodernists like surfers skating across the tops of the waves, having learned “to perceive the ocean as a ‘trajectory’ rather than either a territory (implying a mapping) or a telos (suggesting direction),” then the metamodernist, says Vermeulen, is more like the snorkeler, who gazes into the deep by means of the surface. “[F]or the snorkeler, depth both exists, positively, in theory, and does not exist, in practice, since he does not, and cannot, reach it.”[xxi] The aim to approach the depths of reality, then, is caught in the same “donkey-carrot double-bind” as progress. But the very limits of the medium are also what gesture towards their own transcendence. All that the postmodernists took as a foreclosure of possibilities for the metamodernist opens up a new medium of possibility. The end of the old transcendence becomes the means of apprehending the new. Philosophically speaking, the monism of naturalistic immanence becomes the locus of a new kind of transcendence.[xxii]

It is no accident then, Vermeulen and van den Akker suggest, that metamodern art exhibits a pronounced “neo-romantic turn,” since “Romanticism is about the attempt to turn the finite into the infinite, while recognizing that it can never be realized.”[xxiii] Metamodern art, I would say, celebrates this impossibility as the occasion for infinite transcendence, as movement towards the receding telos engenders “progress” without finitude, “progress” without end. In that sense, the old postmodern strategies that serve to undermine Absolutes are embraced as mechanisms of generation, growth, and discovery. Metamodernists gesture towards the iterative realization of the infinite by employing postmodern tactics for new, progressive ends:

[B]oth metamodernism and the postmodern turn to pluralism, irony, and deconstruction in order to counter a modernist fanaticism. However, in metamodernism this pluralism and irony are utilized to counter the modern aspiration, while in postmodernism they are employed to cancel it out. That is to say, metamodern irony is intrinsically bound to desire, whereas postmodern irony is inherently tied to apathy. Consequently, the metamodern art work (or rather, at least as the metamodern art work has so far expressed itself by means of neoromanticism) redirects the modern piece by drawing attention to what it cannot present in its language, what it cannot signify in its own terms (that what is often called the sublime, the uncanny, the ethereal, the mysterious, and so forth). The postmodern work deconstructs it by pointing exactly to what it presents, by exposing precisely what it signifies.[xxiv]

In this way, deconstructive moves which in postmodernism signaled exhaustions and cynicism are appropriated and redeployed in metamodernism towards reconstructive aims—another key touchstone in all the major formulations of metamodernism to date. Deconstruction, taken further, leads to reconstruction. The loss of the Absolute is a demolishing act that is a necessary prerequisite for infinitesimal progress. Such is the nature of the journey towards an infinite horizon. The goal is in the going and the gains made along the way. As Vermeulen and van den Akker conclude their 2010 essay:

For indeed, that is the ‘‘destiny’’ of the metamodern wo/man: to pursue a horizon that is forever receding.[xxv]

There is, odd as it may sound, an implicit sort of Neoplatonic architecture to what Vermeulen and van den Akker are here proposing. As they say, “metamodern irony is intrinsically bound to desire, whereas postmodern irony is inherently tied to apathy.”[xxvi] In the Platonic tradition going back to Plato’s Symposium, desire (“eros”) is seen as the driving mechanism of the ascent towards higher levels of reality. Indeed, as Vermeulen and van den Akker themselves note in their 2017 treatment, it is precisely eros that Diotima describes in the terms of metaxy. Eros is what bridges the infinite and finite, caught in the middle. In Dumitrescu’s image of Jacob’s ladder, it is the integrating care that ascends and descends, connecting the levels. In premodern terms, such aspirational desire was for the divine realm; in the modern, for earthly Utopia. In postmodernism, that desire was lost, replaced by apathy and relativistic cynicism regarding any form of “ascent.” But the metamodern regains this eros in a reimagined form—as the desire to meaningfully bridge the many recursive levels through a simple integrating earnestness.

But we will leave further such reflections to our consideration of metamodern spirituality and religion later on. For now, we can simply note that metamodern art gestures towards this reclamation of “progress” beyond postmodern apathy through a new approach to transcendence. Here, the failure of finding “the ultimate frame” itself becomes a tool for experiencing such transcendence.[xxvii]

Cultural theorist Raoul Eshelman’s work on the aesthetic strategies of “performatism” are exemplary of this metamodern trend, and inform his own contribution to Vermeulen, van den Akker, and Gibbons’s 2017 anthology. In his essay chapter, “Notes on Performatist Photography: Experiencing Beauty and Transcendence after Postmodernism” (pp. 183-200), he notes that “this affirmative, forced movement towards beauty and transcendence per formam – through form – corresponds to similar strategies in literature, film, painting and architecture.”[xxviii] As he summarizes it in his own earlier work, Performatism, Or, The End of Postmodernism:

A good formal definition of the “performance” in performatism is that it demonstrates with aesthetic means the possibility of transcending the conditions of a given frame (whether in a “realistic,” social or psychological mode or in a fantastic, preternatural one).[xxix]

That is, experiences of transcendence are simulated in metamodern art through artistic means, replicating within the aesthetic frame of the artwork the possibility of overcoming its own given frame. By undermining the worlds of their own creation, the performatist invites the audience to experience transcendence.

Eshelman cites the 1999 film American Beauty as a good example of the sensibility that shines through such performatist curations of transcendence. That film opens and closes with (i.e., is literally framed by) a moving aerial perspective narrated by a voiceover of the main character, Lester Burnham, speaking to us from beyond the grave. In his closing words—while, I would note, we literally look down over the economic symbol of postmodern life, American suburbia—his remove renders him earnest, not cynical, as he movingly reflects:

I guess I could be pretty pissed off about what happened to me, but it’s hard to stay mad when there’s so much beauty in the world. Sometimes I feel like I’m seeing it all at once, and it’s too much; my heart fills up like a balloon that’s about to burst. And then I remember to relax, and stop trying to hold onto it. And then it flows through me like rain, and I can’t feel anything but gratitude—for every single moment of my stupid, little life.

By “getting above” his embeddedness in postmodern life, decentering to a higher, transcendent remove, Burnham can experience only beauty and gratitude. This is wholesomeness not of naiveté, but with all the knowledge of why he should indeed be “pissed off” by the affairs of the world. It is the cinematic equivalent of climbing out of the painting and into the art gallery, such as I described in Chapter 1 as an instance of decentration. The shift in perspective changes the sensibility. Rising above embeddedness in postmodern cynicism and superficiality, one’s attitude shifts. One gains a whole new perspective on things—a positive one (in this case, profound gratitude).

Eshelman sees a broad trend in artworks in the latter 20th and early 21st centuries that emphasize just such meaningful “frame breaking.” Art takes a turn towards stories of earnest transcendence—often by means of deconstructing their own magical worlds (as in Life of Pi, for instance). As he puts it: “All performatist works feed in some way on postmodernism; some break with it markedly, while others retain typical devices but use them with an entirely different aim.”[xxx] Such tactics allow the metamodern to move beyond postmodern deconstruction, by means of such deconstruction, towards new, reconstructive efforts.[xxxi]

NEXT: Part III

[i] Timotheus Vermeulen and Robin van den Akker (2010) Notes on metamodernism. Journal of Aesthetics & Culture 2(1):5677. https://doi.org/10.3402/jac.v2i0.5677.

[ii] Notes on Metamodernism,

https://www.metamodernism.com/.

[iii] Brendan Graham Dempsey (2014) “[Re]construction: Metamodern ‘Transcendence’ and the Return of Myth. Notes on Metamodernism (October 21), https://www.metamodernism.com/2014/10/21/reconstruction-metamodern-transcendence-and-the-return-of-myth/.

[iv] For instance, Linda Hutcheon (2002) The Politics of Postmodernism, 2nd ed. (Routledge, New York), p. 181.

[v] See, for example, Gilles Lipovetsky (2005) Hypermodern Times (Polity Press, Cambridge); Alan Kirby (2009) Digimodernism: How New Technologies Dismantle the Postmodern and Reconfigure our Culture (Continuum, New York).

[vi] Vermeulen and van den Akker 2010.

[vii] From Ihab Hassan (1985) The culture of postmodernism. Theory, Culture and Society 2(3):123-124.

[viii] Vermeulen and van den Akker 2010.

[ix] Ibid.

[x] Ibid.

[xi] Ibid.

[xii] In their more robust 2017 presentation, Robin van den Akker, Alison Gibbons, Timotheus Vermeulen (eds.) (2017) Metamodernism: Historicity, Affect and Depth after Postmodernism (Rowan & Littlefield, London), they unpack this important caveat further than in their 2010 essay. While still emphasizing the modern/postmodern dynamic, they acknowledge that metamodern oscillation entails a movement between these as well as still earlier cultural logics and sensibilities. Metamodernism, they specify, can entail a “harking back…to modernist…or even earlier forms,” and that the prefix meta signals “a being with or among…postmodernist and modernist – and even realist and earlier – strategies and sensibilities.” In evidencing wider recognition of this metamodern turn, they cite with approval Vaessen and van Dijk’s recognition of “a new position that tries to reconcile postmodern and pre-postmodern, humanistic elements” (p. 9). Thus, though they reiterate their earlier point that “there is some kind of cultural predilection, among all of the now-newly available ‘pre-postmodern’ elements, for modernism,” they, too, appreciate that metamodern “oscillation” entails a movement between multiple logics, not just the modern and postmodern.

[xiii] Ibid, 8.

[xiv] They compare it to the way different scotch whiskeys exhibit unique saline flavor profiles despite the fact that salt is not one of the ingredients. A scotch’s saltiness is presumably blown in from the coastal winds. It infuses the taste but cannot be clearly isolated or extracted from the drink.

[xv] Vermeulen and van den Akker 2010, citing R. Avramenko (2004) Bedeviled by boredom: A Voegelinian reading of Dostoevsky’s Possessed. Humanitas 17:1-2, 116.

[xvi] Terry Eagleton (1987) Awakening from modernity. Times Literary Supplement, February 20.

[xvii] Vermeulen and van den Akker 2010.

[xviii] Timotheus Vermeulen (2015) The new depthiness. e-flux 2015:61. https://www.e-flux.com/journal/61/61000/the-new-depthiness/.

[xix] Ibid.

[xx] Ibid.

[xxi] Ibid.

[xxii] This is essentially the thesis of my earlier work, Metamodernism and the Return of Transcendence.

[xxiii] Vermeulen and van den Akker 2010.

[xxiv] Ibid.

[xxv] Ibid.

[xxvi] Ibid.

[xxvii] Similarly, in Chapter 4 of van den Akker, Gibbons, and Vermeulen’s anthology, “Super-Hybridity: Non-Simultaneity, Myth-Making and Multipolar Conflict” (pp. 55-69), Jörg Heiser uses Ernst Bloch’s notion of “Ungleichzeitigkeit” or “non-simultaneity” to discuss metamodern notions of progress in a world where cultural logics of seemingly different “times” find themselves in temporal coexistence. For example, ISIS represents both premodern religious fundamentalism while simultaneously employing modern technology and postmodern marketing strategies. Such temporal incongruencies would seem to undermine simple modernist notions of a universal history of linear progress. At the same time, though, Heiser posits a metamodern notion of relative progress in terms of increasing self-reflection. He writes:

Bloch’s notion of Ungleichzeitigkeit was based both on a Marxist, post-Hegelian philosophy of historic progress and on a more general understanding of enlightenment as a move towards increasing the self-reflexive nature of thought and ethical standards. Even if we were still ironic postmodernists, or whether we have evolved into post-ironic metamodernists, it is evident that simplistic notions of linear progress have long been exposed as illusory and dangerous, and even as we may be tempted by nihilism, it is hard to deny that virtually any idea of reflection and thought – indeed, of philosophy in general – ultimately relies on the assumption that progress is possible, at the very least a progress in understanding what’s going on. Otherwise, there would be no point to any kind of reflection. …As soon as we can imagine how things could be better, a principle of progress is implied. (68)

Such reflections would seem to accord quite nicely with the framework presented in this book regarding metamodernism’s infinitesimal progress through eternal recursion based on self-reflection. As we shall note in the final chapter on the worldview, they also support conceptualizations of the metamodern beyond simplistic temporal periodization schemes.

[xxviii] Raoul Eshelman (2017) Notes on performatist photography: Experiencing beauty and transcendence after postmodernism. In van den Akker, Gibbons, Vermeulen (eds.) Metamodernism: Historicity, Affect and Depth after Postmodernism, 183-200.

[xxix] Raoul Eshelman (2008) Performatism, Or, The End of Postmodernism (The Davies Group Publishers, Aurora), 12.

[xxx] Ibid., xiv.

[xxxi] In this, Eshelman favors a more classically Hegelian framing of metamodernism compared to Vermeulen and van den Akker’s “oscillation.” He writes:

[I]n describing the historical shift away from postmodernism I prefer the good old Hegelian term ‘synthesis’ to the figure of a ‘dialectical oscillation’ between modernism and postmodernism. Although Performatism and metamodernism agree that there really is something new going on, it seems to me here that metamodernism tries to straddle the fence too much on this particular issue. Either we are dealing with a dialectical synthesis resulting in a new stage of historical development, or we are dealing with a static, non-historical oscillation, but not with a ‘dialectical oscillation’ that seems to accommodate both while being neither one nor the other… (Eshelman 2017, 199)

Indeed, Vermeulen and van den Akker’s framing of an “oscillation” vs. a standard dialectical advance (such as is more in line with eternal recursion) has proven to be one of the more idiosyncratic aspects of their theory. It finds explicit critique in multiple instances in their own anthology (e.g., from Eshelman, Toth) and in Dember’s critique of oscillation (see below). Meanwhile, the standard dialectical framing is employed by Hanzi Freinacht and Jason Ānanda Josephson Storm, among others. All of this would seem to make emphasis of “oscillation” or “dialectical oscillation” something of an outlier in the discourse.

Thanks for these articles. Wonderful introduction.

Glad to have been pointed here. Excellent work.