According to the concept of meaning and value advanced over the preceding posts, complex entities strive to update their world models through learning, which provides them the relevant information they need to orient their actions towards optimal goal states. As they do, meaningful knowledge is attained that permits the achievement of still greater levels of complexity, and so on. This process plays out in human culture through the development of symbolic meaning-sharing, which is a form of meaningful information processing able to intersubjectively cohere large groups of individuals in a symbolic world dedicated to achieving collective goals.

As meaningful knowledge is learned by people in societies, it is symbolically translated and culturally affirmed, whereupon it serves to in-form future action and collective organization. A “sense for meaning” is thus cultivated among a society’s members, a honing of predictive accuracy in the direction established by earlier successes, as new information is continually compared against the proven templates of a society’s established meanings. Language allows these established meanings to be reified and reflected upon, and through collective cultural memory these meanings are stored and transmitted to new generations across time via the enculturation process discussed above.

Such meanings will naturally vary in their cultural significance relative to how important they have been for steering society towards continued or enhanced viability. Novel and unfamiliar concepts and behaviors will face, if not ambivalence, perhaps only mild curiosity. More established lodestars will receive varying degrees of regard. But for the learned meanings established as absolutely fundamental to orienting a society towards locally optimal states, there will be especial reverence, care, and devotion. Such meanings we call sacred. And it is according to their “gold standard” that all other collective meanings and justifications are weighed and assessed.[i]

The sacred, then, can be understood as both the symbolic repository of a culture’s most proven meanings and values as well as the informing template or ideal by means of which people assess novel information for meaning. Cultural memory serves, you could say, as a transpersonally aggregated world model by means of which enculturated individuals learn to predict meaning. Embodied predictive processing of cultural meaning with the greatest causal power manifests as intuitions of sacredness.[ii]

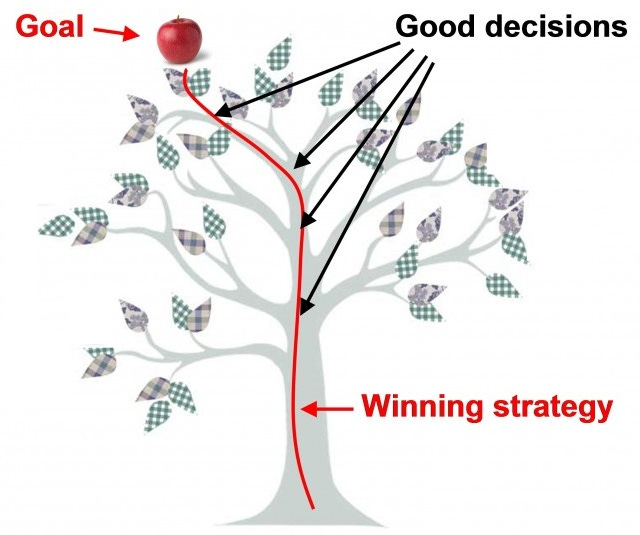

Over time, such collective learning carves out a hierarchy of values relative to the specific environmental conditions of the society. Like the formation of a neural network, the most successful meanings and values become well-trodden and robust, and get deposited into the symbolic social repository as sacred beliefs. The less established, exploratory pathways remain weak, and could as easily lead to failure as to new, more successful beliefs.

Symbolic Learning is the process by which cultures update their collective world models towards more viable beliefs, in the course of which the sacred itself is updated. Because the sacred is both what is updated as well as the guide to more robust meaning, there is both disruption and continuity in this learning process. The sacred does not just change, it develops. This Evolution of Meaning series is an attempt to chart that development.

I will use the word “sacred,” then, to refer to those collective representations of a culture that are superlatively meaningful to it (in the technical sense of meaning as mutual information with causal power bearing on viability). The sacred constitutes the veritable foundation upon which psycho-cultural flourishing depends. It hallows that which sustains and upholds a given society, enshrining the established gains of cognition and conception that make any continued gains possible. It is the proper respect owed to the adaptive path taken, its active shoring up, and the intimation of where it will lead based on where it has been. It is, in short, what is deemed most important to the continued viability of a successful human system–environment relationship.[iii]

One glimpses this sense even in colloquial uses of the word, as the “sacred” has been extended beyond traditional religious discourse into other domains of cultural significance. A cathedral or mosque are readily admitted as “sacred” spaces for religious practitioners, of course, but a secular nation’s capitol and its seat of democratic governance is also said to be “sacred.” Human rights and freedoms are likewise “sacred” in this modern sense. But so, too, is a tribe’s totem or initiation rite “sacred” to its members. For those sensitive to ecology and the dynamic systems that render all life possible, Nature and the biosphere are held as “sacred.”

When threatened or attacked, these sites of the sacred will be adamantly defended by their acolytes like white blood cells warding off disease. That is because, without the sacred, the psycho-social superorganism would break down.[iv] A tribe depends on its totems, religious communities on their Gods, modern secular nation states on their democratic ideals and institutions, etc. They are what ground and orient such societies at their varying levels of size and complexity. They are what keep them from entropic dissolution as well as what propel them towards still greater integrity and scope.

As meaningful information, the sacred also complexifies through Symbolic Learning. In fact, its informational richness increases in tandem with the society’s causal power, as it both permits and demands greater energetic input to sustain itself in the face of entropic dissolution. In this sense, the sacred itself is a kind of dissipative structure, a self-organizing informational configuration far from equilibrium in continual exchange with the environment. One might call this a thermodynamic theory of the sacred. Like all dissipative structures, the sacred complexifies by means of learning, and on the plane of Culture, this learning is accomplished by individual members of society.

As human minds complexify through learning, allowing more information to be related and coordinated, meaningful knowledge increases and the comprehensive scope and coherence of the sacred expands accordingly. The world model extends its horizons; the causal connections between phenomena grow more refined; the profundity of explanatory patterns deepens; the resolution of thought becomes sharper, more nuanced, more fine-grained. Entirely new superlatives of normativity come into view. What is best, highest, greatest, most important, most true, most real are articulated with more clarity and inclusivity. In the process, the prevailing sense of the ultimate becomes successively contingent relative to something more ultimate still, and the sacred outgrows itself.

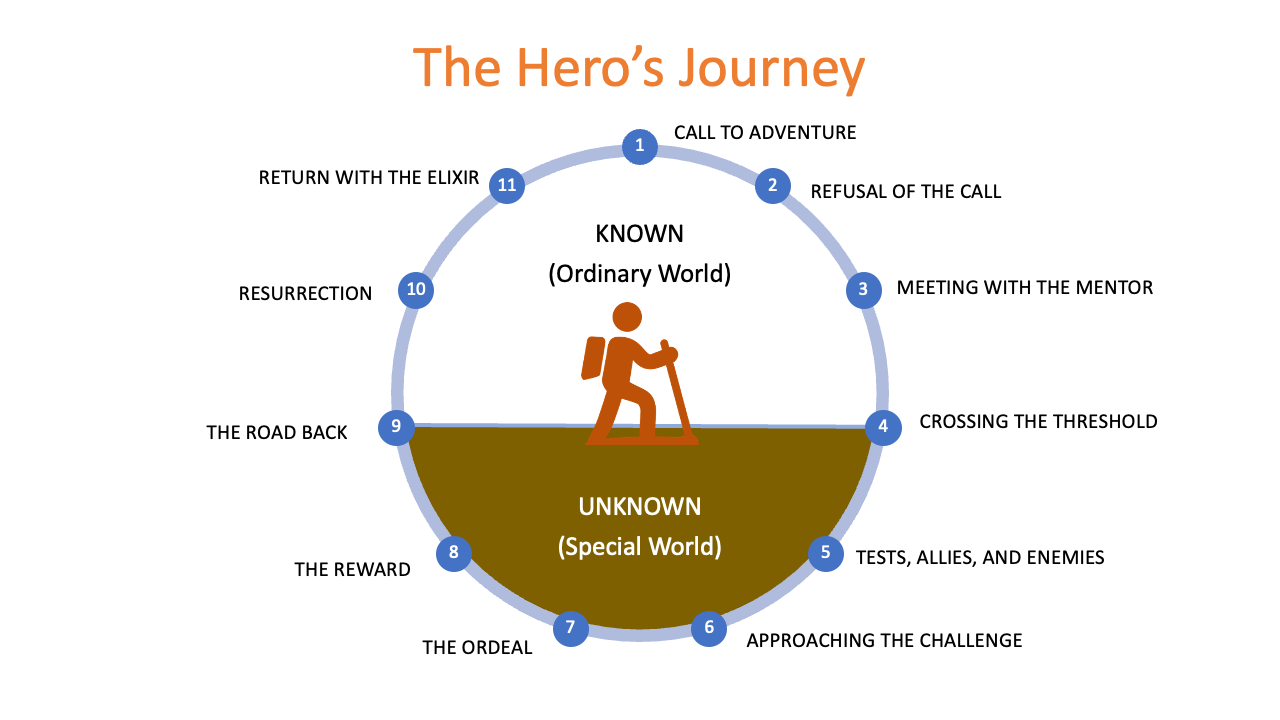

Given how important and, indeed, meaningful this process is, we may wish to appreciate the learning process itself as sacred—or (because it is what gives rise to sacred content) perhaps even as a sort of meta-sacred phenomenon. Learning is the means by which the sacred emerges and develops. After all, it is particularly in moments of breakthrough, of transcendence, of insight, that the sacred is experientially encountered. This is how new depths of meaning get disclosed. Such instances of adaptive learning mark advances into the unknown—a relatively chaotic realm of possibility whose increased entropy does not ultimately disrupt coherence but actually enhances it by the disclosure of still greater structure operating with greater degrees of freedom. But that, you will note, is what complexification is. We might suggest, then, that learning is the archetypal act of transcendence. It is what complexifies the mind, permitting an updating of the world model according to which cultural meaning is (re)assessed.

This meta-sacred act transcends any contextual sacred (e.g., a totem, a church, etc.) for it is the very pattern by which the sacred manifests and develops. Indeed, it is perhaps only because every instance of the sacred is itself a product of this general process that instances of the sacred can serve as a reliable canon by which to interpret novel information. As we shall see, aspects of this meta-sacred process wind up imprinted in specific sacred contents across the complexification process. Some things register as meaningful precisely because they gesture towards the meaning-developing process itself.[v]

We can thus appreciate that something deeper than the sacred underlies the development of the sacred—something more important than any local realization of importance. Predictive processing models of cognition may be indicative of this, as they suggest that it is updating our sense of meaning that is actually most meaningful to us. We operate off of prior information to make predictions, and if that information proves reliable, it is meaningful for us in the sense of maintaining our viability. But successful predictions are boring—by design. All is going very well viability-wise if we experience very little surprise. It means the model is holding. By contrast, it is when we are confronted by new information which may stand to profoundly upgrade the quality of our priors that we become engrossed, transfixed, curious, amazed. As we will see, awe is itself a product of the learning process, a state of wonder aroused by the attempt to integrate a surplus of potentially meaningful information.[vi]

The experience of meaning as profound relevance, as salience, as significance—this arises not so much from any established sacred per se, but from the meta-sacred call to learn, to complexify, to transcend, and update one’s conception of the sacred thereby. New forms of the sacred always lie on the other side of awe.

Awe is the meta-sacred response to information we have not yet processed for its sacrality. It is the mind’s reflex before the invitation to transcendence. It is the liminal state beyond one’s old concept of the sacred and before a new one. It is the blissful open receptivity to an upgrade for one’s meaning-making. It is the condition in which one meets such benevolent chaos as reorganizes you for the better—an incomprehensible fullness appreciated by the mystics as the Mystery. All learning strives to render it known, and all learning ultimately falls short.

What it produces is a series of “ultimates” progressively approximating more and more of that abyss of meaning.[vii] These are the faces of God as they get redrawn through the advances in Symbolic Learning.

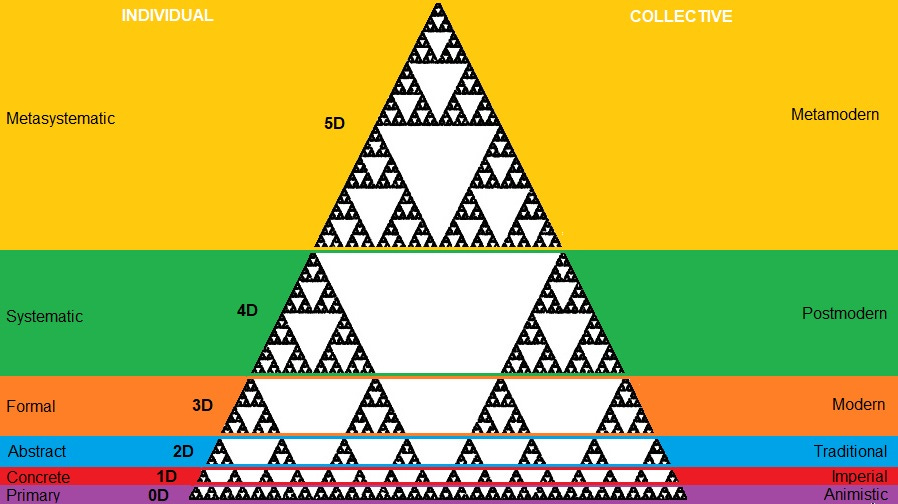

The evolution of meaning has thus been characterized by a succession of increasingly comprehensive and complex articulations of the sacred, to which human minds have transcended by reaching ever higher levels of informational integration and hierarchical coordination. Like other informational structures moving further from equilibrium, the configurational organization of the sacred has undergone a series of phase shifts across human cultural history, a punctuated equilibrium of different states reaching new degrees of complexity as more energy enters the system and organizes what it flows through.

The substrate of this complex adaptive system is not some tangible solid or liquid, but the psycho-cultural system of information processing known as human society itself.

The attractors to which it is drawn therefore correlate to the ways human minds learn to process symbolic information at different levels of hierarchical integration. Meaning and the sacred emerge and evolve out of the learning mind’s distinct Umwelts as it progressively renders more of the Mystery known.

In this way, knowledge and value extend in a graded continuum throughout the learning process of complexification. Feuerbach’s insight that “each plant would declare its own flower the most beautiful” captures this transjective nature of relative good matching relative understanding. But, being himself a theologian, Feuerbach took the idea even further, seeing that every entity must then have its own sort of guiding ideal, its own sacred, shaped by (what we can now call) the normative conditions of its entity–field relationship.

“If God were an object to the bird,” he writes, “he would be a winged being: the bird knows nothing higher, nothing more blissful, than the winged condition.”[viii]

There is, we might say, a God for every Umwelt, since meaning is adjudicated according to the information linking systems to their environment. This line of thought leads Feuerbach to posit that the God-concept itself is always but a given entity’s intimation of ultimate knowledge:

God is thy highest idea, the supreme effort of thy understanding, thy highest power of thought. …God is what the understanding thinks as the highest. But in what I perceive to be essential is revealed the nature of my understanding, is shown the power of my thinking faculty. …As thou thinkest God, such is thy thought;—the measure of thy God is the measure of thy understanding.[ix]

As we shall see, though, a word like “God” is probably better reserved in reference to a particular cultural Umwelt’s conception of the sacred. “God,” at least as an anthropomorphic, supernatural being, is but one shape assumed by the sacred in cultural history, a moment in the complexification of meaning.[x] However, those who use the word “God” to refer to more abstract notions, such as Paul Tillich’s “ultimate concern,” would be employing the term more as I am using “the sacred.” I myself will sometimes speak of God in this way: not as any given moment in the evolution of the sacred, but as the enduring entity being evolved.

Indeed, in the volumes that follow, I mean to show how God in this broader sense has evolved, complexifying through the learning process of cultural evolution. Once we are familiar with the distinct patterns of ontogenetic learning (which the next book will explore [Vol 2. Psyche and Symbolic Learning, coming later this year]) and understand why and how they shape entire collective justification systems (Vol 3. Society and Symbolic Learning, coming next year), we will be ready to track the evolution of meaning, value, and the sacred as they developed across human cultural history.

After 13.8 billion years of cosmic complexification, during which meaning itself was slowly growing more intricate and profound, the sacred at last emerged, full force, in human culture, where God awakened in the mind of mankind. From Structural to Genetic to Cognitive to Symbolic Learning, we come at last to the flower of evolution and consider the unfolding of sacred meaning in the human cultural domain. That will be the focus of our attention in the rest of my Evolution of Meaning series. Stay tuned.

If you find this project compelling, please consider supporting my research into the evolution of meaning.

NOTES

[i] Hence the “paradigmatic” nature of the sacred as emphasized in the comparative religious studies of Mircea Eliade. According to Eliade, man as Homo religiosus relates to the sacred as the perfect template, the ideal type, the primordial reality, and through religious rites returns to that mode of things as they were “ab origine, in illo tempore.” The sacred is the archetypal source of strength and power—an enduring repository, continually open for renewing engagement, for enhancing viability and vitality:

The man of the archaic societies tends to live as much as possible in the sacred or in close proximity to consecrated objects. The tendency is perfectly understandable, because, for primitives as for the man of all pre-modern societies, the sacred is equivalent to a power, and, in the last analysis, to reality. The sacred is saturated with being. Sacred power means reality and at the same time enduringness and efficacity. …Thus it is easy to understand that religious man deeply desires to be, to participate in reality, to be saturated with power. (Mircea Eliade, The Sacred and the Profane: The Nature of Religion (New York: Harcourt, 1959), 12-13)

The sacred is the deep source of paradigmatic reality received through intergenerational transmission. Conforming behavior to its template maximizes being and power (i.e., viability).

[ii] The idea of the sacred as shaping a cultural “world model” finds deep consonance with the theoretical literature, I think. A religious world is a cosmos, a framework for reality that gives meaning and orientation to life. This is exemplified in Eliade’s writings, for instance, who notes:

[W]e could say that the experience of sacred space makes possible the “founding of the world”: where the sacred manifests itself in space, the real unveils itself, the world comes into existence. …[T]the world becomes apprehensible as world, as cosmos, in the measure in which it reveals itself as a sacred world. …Religious man thirsts for being. His terror of the chaos that surrounds his inhabited world corresponds to his terror of nothingness. The unknown space that extends beyond his world—an uncosmicized because unconsecrated space, a mere amorphous extent into which no orientation has yet been projected, and hence in which no structure has yet arisen—for religious man, this profane space represents absolute nonbeing. If, by some evil chance, he strays into it, he feels emptied of his ontic substance, as if he were dissolving in Chaos, and he finally dies. (ibid., 63-64.)

The world-constituting sacred provides the blueprint for the symbolic, linguistically-mediated, transpersonally realized cosmos in which meaningful human existence unfolds. Beyond that order is entropic chaos—a framing we will return to in great depth in following books.

For further consideration of the sacred as the basis of “world formation,” see William E. Paden, Religious Worlds: The Comparative Study of Religion, 2nd ed. (Boston: Beacon Press, 1994) As the organizing framework for his comparative analysis, Paden writes: “Religions create, maintain, and oppose worlds. Their mythic symbols declare what the world is based on, what its oppositional forces are, what hidden worlds lie beyond or within ordinary life. …It is of the very essence of religion to interpret the world” (53-54). Simply put, “the sacred is the foundation of a world” (61). The sacred world carves out an intelligible sphere for human activity that enshrines moral knowledge and collective values as teleological lodestars for guiding the behavior of its members. The individual “downloads” the worldview of their culture as part of ego development, whereby the telos of the individual and the collective become shared.

[iii] This insight allows us to appreciate the truths contained in Émile Durkheim’s seminal sociological reading of the sacred—namely, as the enshrinement of the transpersonal force facilitating social cohesion and generative integration of the collective. In worshipping the shared sacred object of reverence (be it totem, spirit, god, what have you), humans are actually renewing society itself: the superorganism (we might say) sustaining and preserving every individual as parts within the whole.

In his classic 1912 work The Elementary Forms of Religious Life, Durkheim posits:

We can say, in fact, that the worshipper is not deluding himself when he believes in the existence of a higher power from which he derives his best self: that power exists, and it is society. When the Australian is transported beyond himself and feels life flowing in him with an intensity that surprises him, he is not prey to illusion. That exaltation is real, and it is really the product of forces external and superior to the individual. Of course he is mistaken when he believes that this heightened vitality is the work of a power that takes plant or animal form. But his error lies only in taking literally the symbol that represents this being to men’s minds, or the form of its existence. Behind these figures and metaphors, crude or refined, there is a concrete and living reality.

Religion takes on a meaning and a logic that the most intransigent rationalist cannot fail to recognize. The main purpose of religion is not to provide a representation of the natural world… [R]eligion is above all a system of notions by which individuals imagine the society to which they belong and their obscure yet intimate relations with that society. This is its primordial role; and although this representation is metaphorical and symbolic, it is not inaccurate. Quite the contrary, it fully expresses the most essential aspect of the relations between the individual and society. For it is an eternal truth that something exists outside of us that is greater than we are, and with which we commune.

That is why we can be sure that acts of worship, whatever they might be, are not futile or meaningless gestures. By seeming to strengthen the ties between the worshipper and his god, they really strengthen the ties that bind the individual to his society, since god is merely the symbolic expression of society. (Émile Durkheim, The Elementary Forms of Religious Life (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), 170-171)

In our terms, we could say that the sacred represents the shared meanings of the emergent system of Culture, which unite human thought and action towards viability-enhancing goals. Though Durkheim goes too far in presenting what amounts to a reductionist account of the sacred (“god is merely…”), he does capture a profound truth, and one we shall return to in subsequent books.

[iv] Eliade relates a story from the anthropological account of the Australian Aborigines by Spencer and Gillen which has continued to haunt my memory. He writes:

According to the traditions of an Arunta tribe, the Achilpa, in mythical times the divine being Numbakula cosmicized their future territory, created their Ancestor, and established their institutions. From the trunk of a gum tree Numbakula fashioned the sacred pole (kauwa-auwa) and, after anointing it with blood, climbed it and disappeared into the sky. This pole represents the cosmic axis, for it is around the sacred pole that territory becomes habitable, hence is transformed into a world. …Spencer and Gillen report that once, when the pole was broken, the entire clan were in consternation; they wandered about aimlessly for a time, and finally lay down on the ground together and waited for death to overtake them. (The Sacred and the Profane: The Nature of Religion, 32-33)

Love the article. I have to say that as someone who has also used the Sierpinski triangle to explain complexification, I believe the better way is to start with the undifferentiated black triangle and then iterate through the cutouts to show how each successive stage offers a more nuanced and complex view from primary to metasystematic. The way you did it, each stage has an equal amount of complexity since they represent equivalent infinities.

Dammit Brendan