Emergentism | 7. Lineage: V - Integral Theory

The last conceptual paradigm that we will consider here as a meaningful theological lineage of Emergentism is integral theory. Without doubt, the person most responsible for the current state of this school of thought is American philosopher and writer Ken Wilber—though Wilber is himself a synthesizer of various traditions and disciplines (including a number of those we have already considered).

The genius of Wilber’s integral vision lies in the marriage of its comprehensive intellectual scope with its depth of spiritual insight. The nature of this insight, however, is rather different from that so far considered. Specifically, all of the other lineages we have explored thus far arose out of a Western, predominantly Judeo-Christian context. From Hegel to Whitehead to Jung, the re-conceptualization of the sacred and the divine along evolutionary terms unfolded against the implicit background of the personal God of the Bible. Wilber, by contrast, brings a spiritual conception rooted in Eastern spirituality, specifically esoteric Buddhism—a point of departure that has considerable implications for his interpretive framework, as we shall see.

Wilber is also distinguished from the other thinkers above by the advantage of being contemporaneous with the advances of late 20th century complexity science, which he is able to make use of in framing his neo-holistic spiritual vision of an integral philosophy. So he opens his 1995 masterpiece, Sex, Ecology, Spirituality: The Spirit of Evolution, by situating his line of evolutionary thought within the context of insights from general systems theory, cybernetics, and nonequilibrium thermodynamics. Noting the unification complexity science brought to “arrow of time” for both thermodynamics (Matter) and evolution (Life), he writes:

The material world is perfectly capable of winding itself up, long before the appearance of life, and thus the “self-winding” nature of matter itself set the stage, or prepares the conditions, for the complex self-organization known as life. …The new sciences dealing with these “self-winding” or “self-organizing” systems are known collectively as the sciences of complexity…

As we have seen, complexity science returned the idea of emergence center stage, which states that a whole is more than the sum of its parts. With integral theory, Wilber develops his own general developmental philosophy of such whole-part relationships, utilizing Arthur Koestler’s idea of a “holon,” or a “whole-part,” as the basis of an entire metaphysical system.

“In any developmental sequence,” Wilber writes, “what is whole at one stage becomes a part of a larger whole at the next stage.” Ultimately, the universe is comprised neither of matter nor ideas, but holons. Parts form wholes, and those wholes form parts of even larger wholes—just as we have seen. But Wilber provides some novel insights about this process. For instance, he notes: “Each successive level of evolution produces GREATER depth and LESS span.” That is, in the complexification of the Universe, the more complex something is, the more rare it is. Minerals will be plentiful, because they only exist in the domain of Matter; Life will be less plentiful, because it requires Matter and something else. Intelligent Life will be even less plentiful, and so forth. As we move deeper into the Mandala of Emergences, we find that the layers of the greatest depth also have the least breadth.

As we move up the pyramid of complexity, we also encounter greater and greater interior conscious richness. Adopting de Chardin’s Law of Complexity, Wilber agrees that complexity is only the exterior aspect of interior conscious experience. “The greater the depth of a holon,” he writes, “the greater its degree of consciousness.” However, Wilber builds upon this distinction, marrying it with another. Synthesizing the ideas of thinkers like Jantsch and Habermas (who emphasize that individual evolution only occurs within the broader context of a collective environmental framework), Wilber says that all of emergent evolutionary history has Interior and Exterior, Individual and Collective aspects to it, simultaneously.

With this insight, he hits upon the famous “Four Quadrants” model of evolution: the full, nested holarchy of complexifying emergences radiating out from the Big Bang via a “tetra-arising” reality distinguishable according to all four aspects:

As time progresses since the central origin point, and holons build on themselves (i.e., complexity grows), interior cognitive complexity deepens (Upper Left), the exterior structural complexity of the organism increases (Upper Right), the complexity of its environment niche increases (Lower Right), and the complexity of its worldview increases (Lower Left). At any stage of cosmic evolution, all four aspects of a holon generally complexify in tandem.

Wilber is a particularly keen philosopher when it comes to worldview evolution specifically. Indeed, this element of his thought is probably his greatest contribution to the field of evolutionary spirituality. Specifically, he recognizes a particular moral implication from the notion of complexification: namely, the more holistic something is, the more inclusive it is. New wholes “transcend and include” less inclusive ones, making them less parochial and dogmatic and more open and comprehensive.

In this way, emergence is to be seen as a truly developmental process, thus tying cognitive and moral maturation to the evolutionary process more broadly. As he puts it in Sex, Ecology, Spirituality:

[G]rowth occurs in stages, and stages, of course, are ranked in both a logical and chronological order. The more holistic patterns appear later in development because they have to await the emergence of the parts that they will then integrate or unify, just as whole sentences emerge only after whole words.

In essence, “growing up” in a developmentally progressive sense means including more from previous worldviews and becoming more and more inclusive of them—integrating more of the perspectives that came before. “Development,” he writes, “thus proceeds slowly from egocentrism to perspectivism, from realism to reciprocity and mutuality, and from absolutism to relativity.” Just as biological evolution shows a direction towards more diversity and variation, so cultural evolution shows a direction towards more diversity and contextually aware open-mindedness.

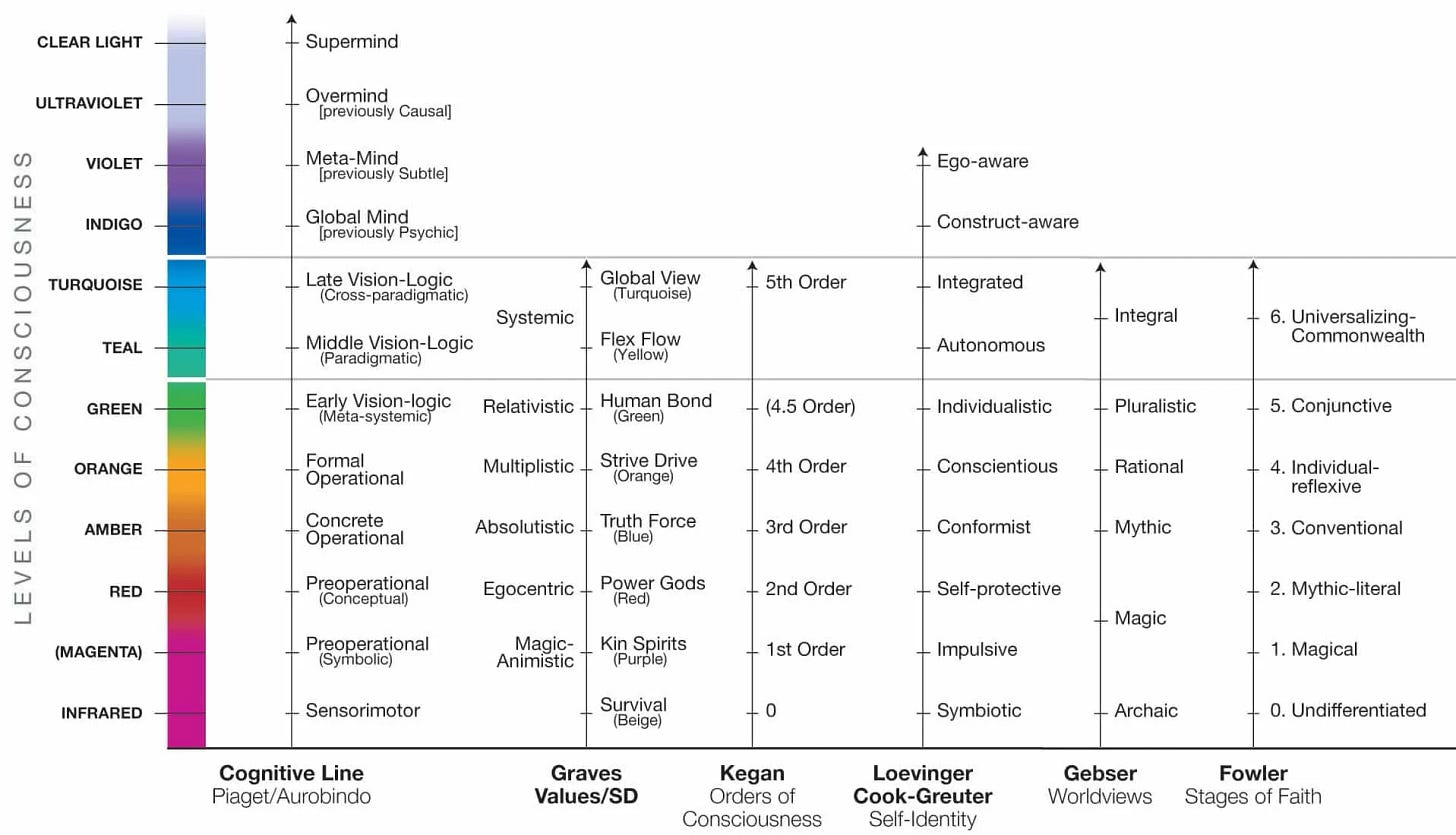

In his brilliant work Integral Psychology, Wilber brings together dozens upon dozens of developmental stage theories, whose synthesis affords him a truly meta-theoretical vantage of human psycho-cultural development. This allows him a meta-developmental stage model that unites everything from Graves’s ECLET model with the stages identified by thinkers like Jean Piaget, Michael Commons, Robert Kegan, Jane Loevinger, Susanne Cook-Greuter, James Fowler, and many others.

As people and cultures evolved through these stages, says Wilber, “each of these structures of consciousness generated a different sense of space-time, law and morality, cognitive style, self-identity, mode of technology (or productive forces)…and types of religious experience.” Ultimately, though, there is a trajectory to this development, as each stage advance equates to “an expansion of ego, an expansion of I-ness, into a higher and wider identity that integrates previously alienated processes.”

The notion of “self” widens, integrates more, becoming more and more inclusive as individual consciousness evolves. As Wilber puts it in Sex, Ecology, Spirituality:

[T]he ego begins more stably to emerge in the mythic stage (as a persona or role) and finally emerges, in the formal operational stage, as a self clearly differentiated from the external world and from its various roles (personae), which is the culmination of the overall egoic realms. …The point is that each of those stages is a lessening of egocentrism as one moves closer to the pure Self. …As we will see when we follow evolution into the transpersonal domain, these developments converge on an intuition of the very Divine as one’s very Self…a Self that is the great omega point of this entire series…of decentering from the small self in order to find the big Self. …The completely decentered self is the all-embracing Self (as Zen would say, the Self that is no-self).

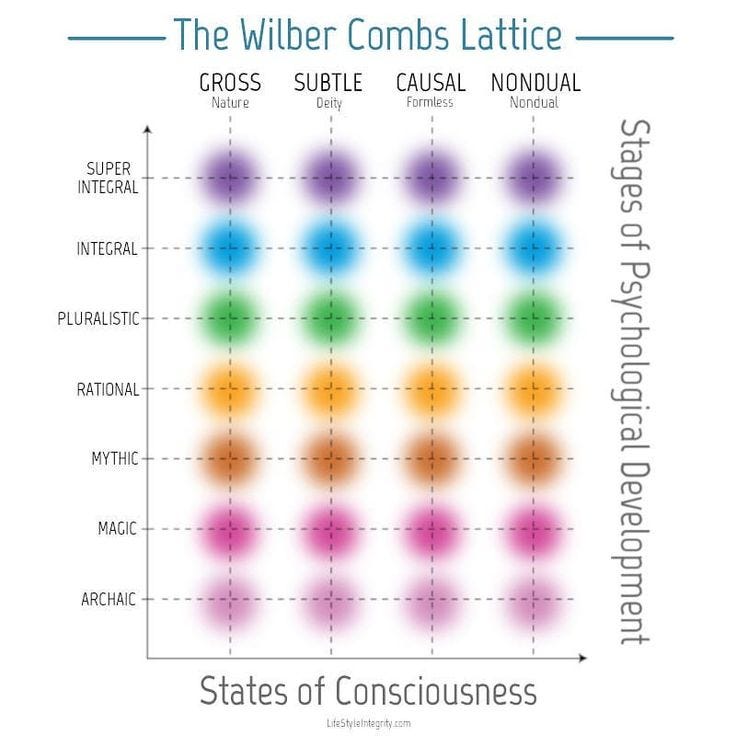

Here Wilber’s distinctly Eastern lens begins to play an important part in his theorizing, as he attaches onto the stages of cognitive complexity devised by the Western neo-Piagetian developmentalists the “transpersonal” stages of mind articulated by the Eastern mystic Sri Aurobindo. More than that, he situates this cognitive developmental sequence as operating across four metaphysical realms: the Gross, Subtle, Causal, and Non-dual, a taxonomy adapted from Eastern metaphysics (sthula sarira, sukshma sarira, karana sarira, and turiya).

Ultimately, for Wilber, it is the formless Non-dual realm that is the true ground and aim of all things, not some historical Omega singularity of maximal complexity toward which we are marching. He teases the idea of a Whiteheadian God early in Sex, Ecology, Spirituality, writing:

And a final Omega Point? That would imply a final Whole, and there is no such holon anywhere in manifest existence. But perhaps we can interpret it differently. Who knows, perhaps telos, perhaps Eros, moves the entire Kosmos, and God may indeed be an all-embracing chaotic Attractor, acting, as Whitehead said, throughout the world by gentle persuasion toward love. But that, to say the least, is quite ahead of the story.

The caginess that allows him to dangle this possibility, however, later resolves into a more emphatic clarity. “‘Ultimate Wholeness,’” he finally suggests, “this is the essence of dominator holarchies, pathological holarchies.” There is no Ultimate Whole; there are only holons in all directions, forever. Humanity is deluded looking for its answer in the realm of Form; it is only in the Formless that enlightenment is found:

And so the question remains: …is there still any sense in which a collective humanity would eventually evolve into an Absolute Omega Point, a pure Christ Consciousness (or some such) for all beings? …Does it even exist? The answer is that It does exist, and we are not heading toward it. Or away from it. Or around it. Uncreate Spirit, the causal unmanifest, is the nature and condition, the source and support, of this and every moment of evolution. …The Formless, in other words, is indeed an ultimate Omega, an ultimate End, but an End that is never reached in the world of form. …Thus, in the world of Form, the ultimate Omega appears as an ever-receding horizon of fulfilment…forever pulling us forward, forever retreating itself.

At this level of metaphysical and mystical speculation, however, words are admittedly imprecise. Is it possible Wilber’s “ever-receding” Omega is the same absolute God consciousness, whose nature is a dynamic, infinite increase in depth and beauty? It would not appear so. Wilber equates chasing after this God to the relentless slog of samsara, the vicious cycle of the world of Form that can only be broken through moksha, liberation:

Evolution seeks only this Formless summum bonum—it wants only this ultimate Omega—it rushes forward always and solely in search of this—and it will never find it, because evolution unfolds in the world of form. The Kosmos is driven forward endlessly, searching in the world of time for that which is altogether timeless. And since it will never find it, it will never cease the search. Samsara circles endlessly, and that is always the brutal nightmare hidden in its heart.

Wilber’s vision thus leads to a rather different conclusion than the other Emergentist theological traditions—to a “telos” in formless Emptiness, and not the rich Fullness of God more at home in the Western tradition.

There is, to conclude, a rich and diverse tradition of mystical and theological thinking in which a metamodern religion of Emergentism can locate its heritage. This tradition is cross-cultural and pan-religious. It is defined not by creed or even a symbolic system, but by a shared nexus of ideas—ideas linking change, becoming, process, development, evolution, history, complexity, consciousness, and non-duality. Such are the Emergentist themes upon which so many schools of thought have already offered their diverse variations, and from which Emergentist theology can draw in its own evolution and development.

In this sense, practitioners who locate themselves in any of these traditions might also identify as an Emergentist. Just as Methodists, Catholics, Pentecostals, and Mormons can all call themselves Christians, the Emergentist label allows for a broad tent of different theological commitments. Or, just as there are different yanas (“vehicles”) in Buddhism (Hinayana, Mahayana, Vajrayana, etc.), so might an Emergentist find their specific “vehicle” in a Jungian framework, another in integral terms, another in idealist terms, and so on. Emergentism is a religion based in the evolutionary orientation towards spirituality that recognizes different shapes of consciousness, different cultural codes, and different God-concepts. There are many ways up the mountain that yield such a vantage.

NEXT: Chapter 8: Ethics and Practices, Part I

Buy the full book here: