Learning as Evolution

Developmental Psychology and the Universal Learning Process

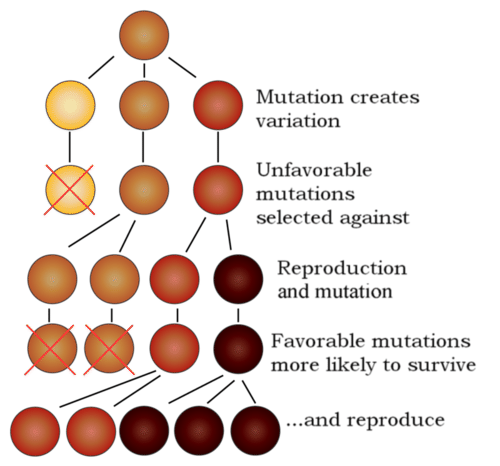

In Volume 1, we concluded that evolution is a learning process, and learning is a complexification process. Indeed, this insight is central to frameworks like Bobby Azarian’s integrated evolutionary synthesis, which posits a deep, process-based continuity between all emergent levels of cosmic evolution through the dynamics of variation and selective retention.[i] At every level, Azarian shows, the persistence of entities in an entropic universe prompts an informational exchange with their environment that is fundamentally evolutionary in nature. Informational configurations that aid viability in the face of existential challenges get retained; those that fail do not. Like an evolutionary tree branching outward, then, the quest for adaptive knowledge will likewise diverge and differentiate until a viable solution is found to fit the niche of a given problem space. Of that vast variety, only a small subset of adaptive strategies actually succeed. Only some information ever proves to be genuinely meaningful knowledge.[ii]

Educational psychologist Gary Cziko offers his own articulation of this idea under the framework of universal selection theory. In his book Without Miracles: Universal Selection Theory and the Second Darwinian Revolution, Cziko tracks the universal learning algorithm of variation and selective retention through biological, mental, and cultural evolution, emphasizing the way entities develop increasing “fit” with their environments through honing different kinds of meaningful knowledge. He opens his book writing:

One of the most remarkable aspects of the universe in which we find ourselves is that this universe has somehow acquired awareness and knowledge of itself. …But it is not only our species that has somehow acquired knowledge of its environment. The fish’s streamlined shape suggests functional knowledge of the physical properties of water. The design of the eagle’s wings reveals sophisticated knowledge of aerodynamics. The deadly effectiveness of the cobra’s venom shows useful knowledge of the physiology of its prey. …In all these instances we notice a puzzling fit between one system and another, an adaptation of an organism to some aspect of its environment. Indeed, knowledge itself may be broadly conceived as the fit of some aspect of an organism to some aspect of the environment, whether it be the fit of the butterfly’s long siphon of a mouth to the flowers from which it feeds or the fit of the astrophysicist’s theories to the structure of the universe.[iii]

Like Azarian, Cziko draws on evolutionary epistemologists like Donald T. Campbell and Karl Popper in his multi-scalar description of evolution as a universal learning process. From genetic adaptations to behavioral updates to theoretical refinements, Darwinian selection, he says, drives an advance in knowledge. “In an important sense,” he writes,

a spider’s legs and feet know something about the terrain that the spider considers home. …Of course, in the case of spiders, we are referring to a type of built-in biological knowledge, not the conscious, reflective knowledge that we associate with human thought. But insofar as biological adaptations are functional and aid in an organism’s survival and reproduction…, these instances of fit clearly reflect knowledge of the world that the organism inhabits.[iv]

Indeed, this sort of adaptive knowledge we have called meaning. Of this sort of meaningful knowledge, that mediated through the information processing system of DNA gets stored in the memory of the gene pool and transmitted hereditarily. I have called this Genetic Learning.

But the meaningful information processed neuronally, through Cognitive Learning, follows the same algorithm. Successful behavior patterns get stored in the memory of the nervous system and transmitted through the animal body in response to stimuli. As the animal–ecology system complexifies and achieving goal-states requires an increasing amount of information processing, behavioral strategies must diversify and adapt through Cognitive Learning.

Here, variation and selective retention of behavior amounts to true “trial and error” learning. Out of the multitude of exploratory attempts, only that small subset of truly helpful actions gets retained as memorized habits—while failures are forgotten. Habitual behaviors that have worked in the past then serve as the basis for the animal to make more successful predictions in novel situations. Should old habits fail in a new scenario, the animal is forced to further refine and update their repertoire of habitual responses, altering existing ones in various ways to meet the novel demands of the environment. In this way, accreted habitual sensemaking structures differentiate, and from this varied diversity again a subset is found that can work in the new situation, and so on. This is how the animal mind evolves—learns—by selectively retaining successful neuronal configurations in response to new information.

Humans quickly develop beyond the limitations of Cognitive Learning, however, with the acquisition of language in infancy. Language, we have seen, allows human minds to evolve through Symbolic Learning—a process that follows its own version of this basic evolutionary algorithm. As we shall explore in great detail below, through Symbolic Learning, linguistically-mediated ideas and concepts also evolve through variation and selective retention. Simpler ideas grow successively nuanced through the need to attenuate and refine older models to new inputs. So the “evolutionary epistemology” of philosophers like Popper and Campbell is deeply akin with the “genetic epistemology” articulated by the developmental-constructivist psychologists.

For Azarian, the point is to appreciate that all of cosmic evolution represents variations on this theme of evolutionary epistemology—from the “learning” done by whirlpools all the way up to the way humans learn scientific theories about them. As he summarizes it:

Since nature is complex, and to some extent intrinsically unpredictable thanks to hidden causes, deterministic chaos, and memory capacity limits, the organism’s model is at some point guaranteed to fail when reality “surprises” it with the unexpected. An organism gets eaten by a predator, a baby fails to reach their bottle, a scientific theory fails to explain new data. What this means is that the model used to predict reality is not completely accurate. It contains a certain amount of prediction error that needs to be corrected. So, what’s the solution? Try something new. The old model worked well enough up to a point, so don’t ditch it altogether. Just vary it a bit and see if it performs better. If it does not reduce surprise, eliminate that variant and try again. If prediction error is reduced, replace the old model with the new one, so that it becomes the reigning theory and the design template for new variants to be based upon. When a model has been updated in this way due to natural selection, adaptive learning, or experimental testing, we can say that knowledge has been acquired and environmental uncertainty reduced. By now, we can see a simple story emerging. By reducing Shannon entropy, or ignorance, life is able to extract the energy it needs to reduce Boltzmann entropy, or disorder. The growth of knowledge and the spread of organized complexity, therefore, go hand in hand. The second law is the impetus for learning.[v]

Thus, key to learning meaningful knowledge at all levels is variation and selection—that is, evolution. Iteratively applied, complexity emerges from simplicity, as adaptive structures accrete. Indeed, this is the same basic logic behind the various AI and machine learning algorithms currently revolutionizing our technology. AI chess-playing programs, for instance—the prototypes of such models—built themselves up from the knowledge gained by countless failures to become unbeatable adversaries through a relentless, recursive bootstrapping process.[vi]

“According to evolutionary epistemology, cultural and technological evolution,” argues Azarian, “even the evolution of chemical dissipative structures, could be explained as products of variation and selection, now understood to be a learning algorithm. …All evolutionary processes are learning processes, and all forms of learning are evolutionary processes.”[vii]

Interestingly, the psychologists developing the first scientific theories of human learning in the late 19th and early 20th centuries hit on just these processes, too. James Mark Baldwin coined the terms “habit” and “accommodation” to refer to the ways learning organisms selectively retain and variegate behaviors in response to their environments, respectively. Writing in 1895, he observed:

Habit is the tendency of an organism to continue more and more readily processes which are vitally beneficial. …Accommodation is the principle by which an organism comes to adapt itself to more complex conditions of stimulation by performing more complex functions. …Learning to act is just accommodation, nothing more nor less. Speech, tracery, handwriting, piano-playing, all motor acquisitions, are what accommodation is, i.e., adaptations to more complex conditions. …But continued accommodation is possible only because the other principle, habit, all the time conserves the past and gives points d’appui [bases] in solidified structure for new accommodation.[viii]

This circular reaction Baldwin saw as the driving motor of mental development, acting in a self-recursive way—and thus functioning as what we today would call a feedback loop. Vitally beneficial habits differentiate to adapt to more complex conditions, which become new habits that can in turn differentiate, and so on.[ix] Through this accretive process, learned behaviors go from simple to more complex.[x]

Drawing on Baldwin, Jean Piaget advanced this basic idea further. What Baldwin called habit he called “assimilation” (from Latin adsimilis, meaning “to make like/similar”). Through assimilation, learning minds process new information in terms of established knowledge. The unfamiliar is interpreted in terms of the familiar, the unknown filtered through the lens of the known. So, for instance, if I’ve only ever seen ducks, the first goose I see will likely get interpreted as some odd sort of duck; if only deer, the first moose as some kind of deer, etc. If there’s a mental scheme we have that’s been successful in the past (i.e., a habit that’s been vitally beneficial), we are inclined to assimilate novel information to it before attempting to accommodate our conceptual framework to newfangled data.

Parents of young children just learning to talk will be quite familiar with this phenomenon. Seeing a horse for the first time, a child raised in a house with a pet dog cries out, “Look, Mommy, doggy! doggy!” The child has no category or scheme yet for “horse” and so assimilates their novel experience to their pre-existing frame of reference. This offers a learning opportunity, as the child will not face success in the future if they continue to mistake horses for dogs. “No,” the mother laughingly clarifies, “that’s not a doggy, it’s a horse. Horse.” “Horse…” the young child thoughtfully repeats to herself, differentiating her mental category of “horse” from “dog” and thus accommodating her mental framework to differences in the world instead of simply assimilating them to what she already knows. Now, when she again encounters a horse, she can apply the new term and, meeting no resistance, comfortably assimilate her perception to the category.[xi]

Through such assimilation and accommodation, said Piaget, the learning mind is continually finding a dynamic equilibrium with its environment. By equilibrium, Piaget didn’t mean static uniformity (as in the sort of thermodynamic equilibrium discussed earlier in Volume 1), but rather a dynamic steady-state or homeostasis such as far-from-equilibrium organisms find with(in) their environments.[xii] Such a mental equilibrium is found via a continual balance between the need to use existing mental categories to navigate the world and the need to update those categories in light of new information. Too much assimilation and we ignore vital particularities and differences in our environment; too much accommodation and we miss the forest for the trees, unable to make use of valuable generalizations. (As we saw in Volume 1, John Vervaeke and colleagues have identified the same basic dynamics governing all animal meaning-making through “relevance realization.”)