Introduction: What Is the La Forge Gospel?

The text you are about to read is, simply put, the most significant and consequential archeological discovery to be made in the last 500 years, if not in the history of archeology itself. For, if genuine, it represents the earliest known account of the life and work of Jesus Christ—one that completely revolutionizes, in fact, our understanding of the figure, his mission and his message. The Qumran scrolls, the Nag Hamadi codices—all pale in comparison to such a find. For here we glimpse the most revered and influential man in all of Western civilization anew. And the image we get is rather different from the one inherited from the canonical Gospels and established orthodox tradition. Indeed, if authentic (as I believe it to be), this first gospel requires a radical and complete transformation of all our beliefs and assumptions about arguably the most important person to ever live. With this text, the world is invited to meet Jesus of Nazareth again—for the first time.

Up until now, two distinct understandings of Jesus have largely dominated the popular conversation: 1) the traditional theological account of him as the divinely-appointed, miracle-working Son of God, sent down to save the world from its sins by means of a sacrificial death…

…or 2) the historical-critical account of an apocalyptic preacher with delusions of grandeur, whose radical message of impending divine judgment got him into hot water with the authorities and, ultimately, killed.

The first understanding was hammered out amongst churchmen and theologians once the dust had finally settled from the early battles over canon and creed; the second has only solidified since the late 19th century, but maintained ever since in academic circles with all the same fixed inflexibilities of established dogma.

The document you are about to read upends them both. According to my reading, the text here describes not one miracle (if by ‘miracle’ we mean the magical breaking of nature’s laws). Nor does it present anything like a “thorough-going eschatology” of apocalyptic expectations and imminent divine wrath. Rather, the Jesus we find in this gospel is rooted in and celebratory of Nature as it is, with the Divine breaking through not in magical signs and wonders but in meditative insight and a contemplative unio mystica. Here, Jesus appears to us less as the empowered exorcist, more the Eastern sage; less the prophet of repentance and reckoning, more the poet and practitioner of wisdom and well-being.

And yet, for all these differences, so much of the same enigmatic figure familiar to us from the centuries still shines through as well: the passionate emissary of Divine insight, defiantly challenging the religious authorities of his day with novel and revolutionary understandings of God; the warm and welcoming advocate of outcasts, exuding openness and hospitality to all so-called “sinners” with an extravagant mercy and disregard for moralistic judgment; the scourge of haughty hypocrites and friend to earnest seekers; in short, the good shepherd and the prince of peace. Even from so far a distance, and in such a different light, that unmistakable essence still comes through clearly and unimpinged.

I have spent my lifetime dedicated to the task of uncovering the world’s hidden wisdoms, to seeking out and sharing with the world the buried treasure of ancient insight—especially after it has been so long censored or covered-up by powerful religious institutions, governments, and other ‘guardians of knowledge.’ Today, I can say that none of the revelations of any of my previous investigations—from books like Our Lost Sacraments: Entheogens and the Early Church, to Yahweh and the Goddess, to Sophia’s Spies: Secret Dispatches from a Vatican Librarian—none of them, truly, even come close to matching the profoundly momentous quality of the revolutionary discovery published in this book you’re about to read.

For such a discovery, I must be clear, I myself take no credit. My role in this saga has been merely that of the investigator, the researcher, tracking facts and following leads as best I could to the end of the line. Thus, what I have always said is today more true than ever: namely, that if I have done anything, it is only to re-discover what had already been found by others. In this case, the rediscovery is itself an important part of the story. For, honestly, the history of the text you’re about to read is nearly as fascinating as the content of the text itself. Though even if it were not half as compelling, but dry and relentless as the desert from which it came, this story must be told. For a proper understanding of this gospel—of what we can know about it, and what we can only guess—for a proper context for all that’s related here, all hinges on appreciating the circumstances by which it was discovered, lost, and found again…

The Story of the Gospel’s Discovery

Pierrot François la Forge was a talented young French archeologist just starting out on a promising career when he arrived at the Albright Institute of Archeological Research in Jerusalem to assist on a new dig. The year was 1954, and the Institute was still abuzz with energy from the ongoing discovery (begun in 1947) of the so-called “Dead Sea Scrolls”: ancient manuscripts from a lost community of monastic Jews which would eventually help rewrite our whole understanding of ancient Judaism. Indeed, the period was a golden age for such revolutionary finds. Only a couple of years before that, in 1945, a collection of thirteen leather-bound codices were discovered in sealed jars at the village of Nag Hammadi, Egypt. These scrolls contained long-lost “Gnostic” Christian scriptures, including the now-famous Gospel of Thomas.

Texts such as these were once completely stamped out as “dangerous” by Church authorities. As a consequence, they were lost to history. But finds like this changed all that. Suddenly, through these miraculous discoveries, ancient wisdoms were returning to the light of day, through archeological finds—and thus at a temporal and geographic distance from the stifling grip of the Church, allowing them to become disseminated and widely known by millions of people.

La Forge shared in the collective excitement of his day around these amazing finds—but his work was of a different sort. The dig for which he came to Jerusalem and on which he was about to assist was a far more conventional affair: less the stuff of Lara Croft or Indiana Jones, more the methodical toil of a forensic scientist’s residency (that is, the typical drudgery for a low-level scholar such as he was, then just embarking on a career in the field).

An orphan from an early age, la Forge had been placed in a Jesuit school for boys as a child, where he had, from his earliest years, shown exceptional academic promise. His abilities were noticed and, by means of a special Church scholarship, he was sent to the Lycée Louis-le-Grand. There, due to an early passion for his faith, he studied Oriental Languages, with the dream of one day becoming an archeologist in the Holy Land.

Originally passionate about the New Testament, his focus suddenly switched to Ancient Near Eastern mythology when he arrived at the Lycée, where he excelled. Abandoning his Historical Jesus studies (then quite popular), he now turned his energies to mythology, specifically the ancient Ugaritic Baal Cycle texts (recovered from Ras Shamra in 1928 accidently, as it happened, by a local peasant plowing his field). La Forge’s assignment at the Albright was destined to be just the first in a promising career in ancient Canaanite studies (c. 12th century BCE).

But the young man was also ambitious. When not on duty at the dig site, he devoted the totality of his spare time to following leads on potential big discoveries elsewhere across Palestine. To this end, he made close contacts with antiquities dealers in the Old City in case any sensational new pieces should come on the market, and kept an ear out for any rumors of new fragments or treasures found on the desert’s surface (which might foretell even greater treasures beneath). He was clearly eager to be a part of the sort of momentous discoveries then rocking the field, even while he had yet to make a name for himself by means of the standard academic channels.

However, fate (as they say) rewards the bold.

One day, while buying some fruit near the Damascus Gate, he heard from a local merchant whispers about some interesting bronze pieces that were apparently circulating in a desert village much further south. By the name, la Forge knew the village to be situated close by a decently-sized tel, which, according to his notebooks, excited his curiosity.

The young scholar decided to check it out for himself. Making his way south, he hired a Bedouin man to guide him out to the remote desert village. Loading up his tools and provisions onto his camel, the two set out early in the morning on the long, grueling trek.

That night, as the extreme daily temperatures of the Negev fell with the sun, his Bedouin guide finally dismounted from his camel and began to make camp on the dunes. The man prepared a fire, gathering some brush and shrubs from the surrounding landscape. La Forge watched absent-mindedly as his guide then took some kindling paper from one of his sacks and got the fire going with it…

Attracted by the warmth of the new blaze, la Forge drew closer and sat down by the flames, slowly turning his eyes down to the coals. When he did, he caught sight of some of the still-burning paper near the embers—and saw: Greek letters…

Immediately, he snatched the smoldering piece from the flames and held it up for eager inspection under the fading sun. “There,” he records in his journal, “still clearly visible, I saw it: in Greek, ὁ Ἰησοῦς — Jesus.”

Frantic and astounded, la Forge berated the Bedouin, demanding he tell him where the paper had come from. Flummoxed, the Bedouin explained that, while digging a well with his brother-in-law a few days earlier, the two had hit a jar buried beneath the sand. Inside, they found scraps of old paper, which, due to their incredible dryness, the man then put to the best use he could think of.

La Forge was flabbergasted. He demanded the Bedouin abandon their current course for the bronze pieces he’d heard about and take him instead to the well at once. And so they went.

Once at the site, the anxious archeologist got to work. With his shovel, he started digging a number of holes around the well, until—at last—he finally struck something, and heard it break.

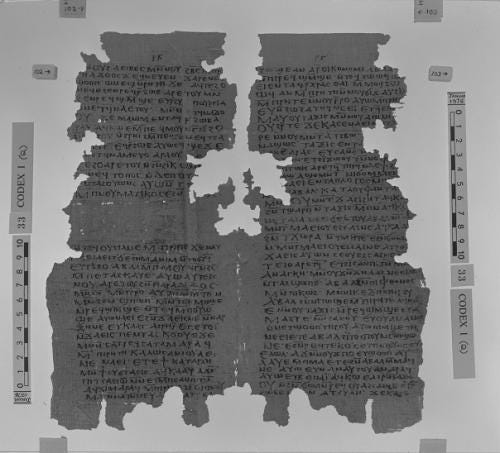

Digging with his bare hands, he unearthed a number of jars: each one containing long, brittle fragments of ancient text. A cursory assessment suggested all were segments of a single extended document. However—owing both to their intentional separation for storage in the jars as well as the inadvertent decay over the years—the document had broken up into multiple, distinct pieces: twelve “scrolls” (as la Forge referred to them in his notebooks).

Elated and curious, La Forge brought the scrolls back to the Albright Institute for further inspection—but apparently did not whisper a word of them to anyone. A note in his journal reads: “Must do thorough overview of text before sharing”—according to which we might deduce his thinking: namely, that he wished to give them his own rigorous academic treatment and analysis before stepping out on a limb and making them known to other scholars—and, consequently—the world.

And indeed, given the academic climate of the day, such a thing is entirely understandable. Handing them over to an institution right away would most certainly have cut off his own access to them, diminishing his role in their study and thus stymying his attempts to advance by merit in his field. This was his find, he felt, and he would ensure everything was fully in order before exposing everything through report. And, to be sure, had his efforts gone according to plan, Pierrot François la Forge would, without doubt, be as much a towering name to us today as any Sir Arthur Evans, Heinrich Schliemann, or Leonard Woolley.

And so he went to work in secret. To keep wear on the fragile ancient texts to a minimum, he took microfilm pictures of each scroll. That way he could inspect and handle them without worry. The originals he hid in a false drawer of his escritoire. Working from the microfilms, then, he began piecing back together the document in its original order as best he could. Indeed, his notebooks—where legible—reveal a highly capable scholar working slowly and methodically, yet in great haste. Much hung in the balance, after all.

Over the course of a few weeks, though, he had apparently done enough work to generate a rough translation based on his reconstruction of the text. Soon, he would be ready to share his discovery with the world—to great acclaim and recoion.

But fate, it seems, had other plans.

On September 2, 1954, while back at work at his official dig assignment, and with his intensive effort temporarily on hold, an unstable embankment collapsed, destroying the multi-story scaffold on which he was working, and sent Pierrot la Forge (along with another unlucky archeologist) to a most untimely death. He was only 24 years old. With him went all knowledge of his secret discovery. All was immediately and, it would seem, irrevocably cast into oblivion. Having never told anyone of his gospel discovery, there was no one to pick up his work where he had left off, or alert the world to such a momentous find.

In fact, matters were even grimmer than that. Because of his lack of any immediate family, there was not even a funeral held for the young scholar. Instead, all of his personal effects at the Albright—including all of his books and, yes, his pending research, notebooks, and microfilms—were simply boxed up and sent over to the École Biblique across town for indefinite catalogue and storage. There they would sit—for over 60 years—collecting dust in total obscurity…

The Story of the Gospel’s Re-Discovery

Until, that is, a new digitization project got underway at the École archives early last year. With some new grant money from an American billionaire (a former CEO, as it happened, and also a former orphan educated by Jesuits), an initiative was set in motion that aimed to scan and catalogue the library’s entire archival materials. Going through the old collections, unpaid interns made slow but steady work pulling down countless boxes from the stacks, scanning the various documents within, and filing them all into an online database. This was how I at last came to enter the picture.

Some people, you see, are always on the lookout for things like lost scriptures. Over the course of my career, I have assembled a vast number of resources for research and investigation into all manner of hidden and occult religious materials—whether that be for work like In Search of Rome’s Pyramid or, more recently, The Real Shroud of Turin. I am, as you might imagine, always on the hunt for information about newly discovered texts, tablets, excavated tombs, etc. And so it was that, earlier this year, while doing a routine aggregating database search for “LOST GOSPEL,” I was struck by one of the hits.

Somewhere in Jerusalem, it seemed, at the École Biblique, a trove of notebooks, haphazardly digitized by careless interns, was referring to a never-before-known “lost Gospel”; “very secret”; and discovered back in “1954”—and, apparently, no one had ever even heard about it!

Without delay, I jumped on a plane and made contact with my agent in Jerusalem as quickly as I could. Immediately, we began to assemble our documentary crew (the one I used for Queen David and Is there a Code in the Bhagavad Gita?) to chronicle our efforts. One day, while shooting some preliminary stock footage, and to all of our unexpected elation, we were granted by the library full access to la Forge’s materials through a special arrangement—including, yes, the precious microfilms he had taken of the scrolls!

The original documents were, however, not among the contents of the boxes. Presumably they remained untouched in la Forge’s escritoire—wherever that may be. Due to a number of renovations at the Albright throughout the years, no such article of furnishing from the period still exists there. The microfilms are thus the only known testament now to this earliest of Testaments. A handful of small pictures taken in 1954 are the closest we will ever come (barring future re-discovery) to the first gospel ever written.

We wasted no time. With support from my then-publisher, we were able to bring in a number of scholars to assess the microfilms, to review la Forge’s translation of the scrolls, add chapter and verse divisions, and generally ready the texts for publication.

As is always the case, however, academic consensus is never 100 percent. Some of our so-called “experts” (presumably out of consternation from the implications of the discovery) insisted the scrolls must be inauthentic. They refused to sign off on our description of the text—though the roots of their apprehension were clear enough to me. Academia has, most unfortunately, but without question, become at last just as much a bastion of Old Thinking and dogmatic prejudice as the Church ever was. Our publisher, however, lacked my degree of conviction. Getting cold feet, they decided to back out of the project altogether.

But I was undeterred! I was confident then, and remain so to this day, that what I had in my possession was undoubtedly the archeological find of the ages—and a text not just of historical value, mind you, but, indeed, of spiritual value.

And so it was that, seeking a new distributor, I presented the idea ultimately to Palimpsest Press, which has since most sensibly thrown its full support behind the endeavor (albeit with the hyper-cautious caveat of adding some additional perspectives regarding the text in some addendum form or whatnot).

Well, appendix perspectives are a small concession, as I see it. For the document printed here is of a truly revolutionary quality, and deserves to be disseminated the world over, untrammeled by censorious institutions, unsullied by biased assessments, and open for all to see. I am convinced that, whoever should read its verses with an open mind and an impartial heart will not be able to doubt its significance and palpably authentic nature.

It is, once more, and for the first time, what the gospel was always proclaimed to be: good news. And to hear such a thing at last from the mouth of Jesus of Nazareth—who has been, for far too many and for too long, a name only of judgment, fear, and division—this comes indeed as a most shockingly welcome revelation! Here is a Gospel without ultimatums, damnations, or superstitions such as the Church would impose. Here, rather, is a Gospel that sets us free from Sin—by rejecting its very premise. Here is a Gospel that does not say we must be forgiven by God and at war with the world, but laughingly asserts that we should be one with God and a friend to all mankind! Here, indeed, is a Gospel of good news.

Will you give it a listen?

CONTENTS The First and Second Scrolls CHAPTER 1 Introduction CHAPTER 2 Jesus’ Awakening CHAPTER 3 Preaching to the Religious CHAPTER 4 Jesus Gains Followers CHAPTER 5 Befriending Sinners and Tax Collectors CHAPTER 6 Jesus Scandalizes the Clergy The Third Scroll CHAPTER 7 Sermon on the Mount The Fourth Scroll CHAPTER 8 On the Nature of the World CHAPTER 9 Parables of the Kingdom CHAPTER 10 On Sacred Symbolism The Fifth Scroll CHAPTER 11 Jesus at the House of a Pharisee CHAPTER 12 Sermon on the Sea CHAPTER 13 On Dogma and Dogmatists The Sixth Scroll CHAPTER 14 On Not Worrying about Life CHAPTER 15 On Riches The Seventh Scroll CHAPTER 16 On Meditation The Eighth Scroll CHAPTER 17 The Wedding at Cana CHAPTER 18 The Religious Authorities Plot CHAPTER 19 The Mourning of Lazarus The Ninth Scroll CHAPTER 21 On the Empty Religion of the Clergy CHAPTER 22 On the New Spirituality CHAPTER 23 Setting Out for Jerusalem The Tenth Scroll CHAPTER 23 Approaching Jerusalem CHAPTER 24 On Building the Temple of God The Eleventh Scroll CHAPTER 25 The Woman Caught in Adultery CHAPTER 26 Jesus Condemns the Clergy CHAPTER 27 Jesus Overturns the Tables in the Temple The Twelfth Scroll CHAPTER 28 The Last Supper CHAPTER 29 Jesus Washes His Disciples’ Feet CHAPTER 30 Gethsemane CHAPTER 31 The Trial of Jesus CHAPTER 32 The Crucifixion CHAPTER 33 The Burial of Jesus and the Women at the Tomb