Level 1 Practices: Organization

But first things first. Developing an Emergentist spiritual practice begins by coming into right relationship with the basis of all things, Matter.

Previous worldviews have struggled finding such a relationship, and have tended to fall into one extreme pathology or another. Traditional religion, for instance, tended to denigrate Matter, contrasting it with supposedly immaterial Spirit. Whereas Spirit was considered pure and holy, Matter was base and vile. This perspective had the unfortunate consequence of rendering, well, everything in the world fundamentally corrupt in the eyes of the spiritualist. Indeed, it’s this negative view of Matter that causes the fundamentalist to seek escaping from the world for a world beyond. This traditional dichotomy has been the cause of untold amounts of unnecessary guilt, shame, and suffering, as religious ascetics pitted spirituality against reality, and even measured their religious merit in terms of just how much punishment they could inflict on their material bodies.

With the rise of modernity, thankfully, such perspectives came to be roundly criticized and maligned. Matter rightly came to be appreciated in all its profound importance as the true basis of reality. Unfortunately, though, this very insight became, as we’ve seen, the source of a whole new pathology: materialist reductionism. If it couldn’t be seen and measured, it wasn’t real. Matter was the only reality—a perspective which has led, in turn, to its own colossal share of suffering, through a materialism (in every sense of the word) that is destroying the planet (cf. the meaning crisis, p. vii).

Between these two extremes of Matter’s denigration and absolutism lies the healthy and important truth. Matter is the base, yes, but it is not on that account debased. Matter is fundamental, yes, but it is not on that account the ultimate.

Matter is the least complex of the emergences, and thus the least conscious. At the same time, we must not forget that all consciousness that emerges has a material substrate. Indeed, the emergence of God is itself a material event! There is no immaterial, super-natural divinity above us, only an embodied and natural divinity before us. If it is to exist, God consciousness must be incarnated. As such, Matter is not something to balk at; it is the very body of God. Matter is divine, a phase of God’s realization.

There is, then, no room in Emergentism for any of the ascetic’s deeply misguided self-hatred of the body or “mortification of the flesh.” (Nor, being also Life and Mind, should humans look askance at our bodily drives, our sexuality, or our emotions.) Emergentism is thus deeply pro-Matter, pro-substance, pro-existence. It says Yes to these, even as it recognizes that they are not the highest, most rarefied elements of existence. Emergentism celebrates the theophany of God in Matter, and encourages spiritual practices in this vein.

So what might that look like?

First of all, it is worth recognizing that, at the root of all things, there is a relentless conflict, an antagonism as old as time itself, a continual cosmic war—that of order vs. chaos. Entropy is always bent on decreasing free energy and configural organization, even as Matter manages to use this very tendency to organize itself into more and more complex forms. In this struggle, we should be Matter’s ally.

Mundane as it may sound, our spiritual lives begin by simply “keeping it together.” To resist the draw of breakdown, randomness, and disorder. To fight dissolution, and continue the Universe’s improbable journey of creating more structural integrity. To not only maintain form and complexity, but add to it, expand it, deepen it.

Perhaps this first calling doesn’t particularly sing to our souls as any great theological act (the ancient wisdom “Cleanliness is next to godliness” notwithstanding). And, admittedly, we are still dealing with the simplest, most basic level here. On the other hand, we should not underestimate the spiritual impact of feeling robustly put together, and even constructive, adding more order to the world than we take away.

Just consider that a message as simple as “Clean Your Room” from a Canadian psychologist and self-help author could land as spiritually transformative for millions of people the world over.

We all have to start somewhere, and we can expect little progress on our spiritual journey towards mystical God consciousness if we cannot yet hold our own in the basic struggle against chaos and entropy—the draconic devil of decay, death, and meaninglessness if ever there was one.

Towards this end, the order in the world should be a cause for true reverential awe and inspiration. The fact that there is something instead of nothing—and such a something as billions and billions of spiral galaxies and supernovas and suns—this should astound us and lead us to deep contemplation of the Universe in prayerful reflection. The skies are the body of God—a true Heaven: not as our disembodied destination but as our material home.

The word “consider” comes from a Latin word meaning “being with the stars,” and so Emergentist praxis would encourage frequent consideration of the celestial glory that is the body of the awakening Universe. As Joseph Campbell once observed:

[I]f wonder and humility are the best vehicles to bear the soul to its hearth, I should think that a quiet Sunday morning spent at home in controlled meditation on a picture book of the galaxies might be an auspicious start for a voyage.

“You are dust,” we read in the Bible, “and to dust you shall return.” We are, indeed, not just dust, but stardust. Every atom of our being was forged in the hearts of stars, then seeded throughout the Universe in grand supernova fireworks—an amazing evolutionary process that wended its way towards our own self-consciousness. Even the tiniest grain of sand is a celestial miracle, part of the grand epic of cosmic Self-assembly and Self-awakening. Growing aware to the glory of things is the heart of the Emergentist sensibility, and the aim of its spiritual practice.

More than that, we do not simply consider the minerals of the earth, but consider them in ourselves. तत् त्वम्—Thou art that. The first principles of physics conspired to make your bones. We are chemical constructions. In the aim of molecules towards entropy lies all our aspirations and intent in embryo. We are seeking to be angels far from equilibrium. We are awakened Matter.

Such insights might meaningfully and practically come together in the intentional construction of sacred space—an organizational offering that brings a focus toward divinity out of (what had been) mere scattered, disordered stuff. The making of altars, shrines, natural sculptures, stupas, etc. is a valuable practice to engage mere Matter in such a reverential manner. It is, you could say, the cosmic act of theophany in miniature; an assembly of parts to form a divine whole.

In such practices, we find a meaningful continuity with the rich religious traditions of the past. In an altar, for instance, the sense of the sacred emerges from simple material items in aesthetic and symmetrical configuration. The icon acts as a medium to channel our gaze by means of material beyond material—into the gaze of God consciousness itself. The icon, you could say, is more than a sum of its parts.

Beholding Matter, and appreciating it as a constituent of our very being, is an invitation to consider the conscious depth lying latent in material. Emergences are quantum leaps, yes, but they are also phenomena on a naturalistic continuum. In a deeply meaningful way, the difference between you and a rock is one of degree, not kind. There is a profound continuity between dust and divinity. And such a connection transubstantiates even the humblest of substances into Godstuff. In this way, God is also stardust, and you are the stuff of God.

Level 2 Practices: Vitality

Emergentist practices that relate to the level of Life are concerned with the basic constituents of biological existence. The “animalness” of the world and ourselves is still a ways off from this vantage; here we are dealing purely with Life at the root, with living in its essence.

It is at this level that value first enters the field of concern—not complex values like ideals or morals, but basic value, a better and worse, a pro and con. Life must meet certain requirements if it is to maintain itself and stay far from equilibrium; because of that, there arises a good for and a bad for for an organism. If only in its rudimentary form, the life force is now in play, and the life force is what speaks—what screams—the good for. The guiding metric of normativity is simply health. Vitality. Vigor. Strength.

We do well when we connect with this will to health in ourselves and in the world. What is thriving, and what is withering? What is ascendent, and what is decadent? In our Emergentist ecology of spiritual practices, we should not neglect this sensitivity, but seek for ways to nourish ourselves as living organisms at this level. Moving, striving, pushing our bodies, fighting inertia—these are not just mundane necessities, but spiritual imperatives. Life thrives by becoming anti-fragile, by stressing the system to improve the system. It is not just in living but feeling alive that we connect to this level. To this end, any sort of physical exertion or exercise is of inherent value.

Life is an organized flow of energy. That energy is what complexifies the Universe, makes it grow, increases its consciousness. The energy causing your heart rate to increase and your blood to pump is the same energy that caused Life to emerge and clumps of Matter to become self-conscious. The exhilarating drive to live to the fullest is the very wellspring of God. The will to power, as Nietzsche called it, is not the cynical antagonism to spirit, it is simply its cruder form.

The whole Universe has been unfolding in a developmental process leading from dirt to divinity. At the core of that process is a drive, an urge, a compulsion, an attraction, an eros at the heart of all things. That is why Plato rightly compared the desire for divine transcendence to the desire for sexual intercourse. It is ultimately one and the same motive, just at different stages of sophistication and refinement. The spiritual life is an embodied life, and one that stays deeply connected with its vital forces and drives. When these erode, the “higher” life of the mind and spirit suffer accordingly. Sex is also divine.

So thrive, move, dare, struggle, revel, strain. Aspire and perspire. Don’t just live, feel alive. Cultivate an ecology of Life practices that keep you flourishing at the level of your biology.

This means, crucially, maintaining a nutritious diet especially. Food has always been an important part of religious traditions. Dietary restrictions are common in different faiths, from the kosher laws of orthodox Jews to the vegetarianism of Buddhists to the abstention from beef of Hindus. For its part, Emergentism also articulates a specific dietary regime as an implication of its worldview.

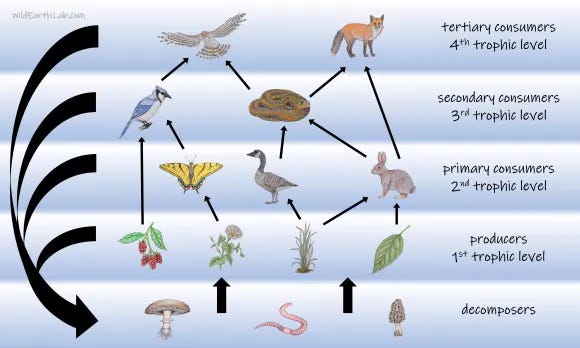

Complexity deepens consciousness, and deeper consciousnesses experience suffering more acutely. Cultivating, killing, and eating a carrot is thus very different from cultivating, killing, and eating a pig. One is at the level of Life, the other is rather high up the spiral of Mind. One has little if any consciousness; the other has a highly developed nervous system and brain.

Human beings are unique in that we are the only (known) complex organism to inhabit the domain of Culture, where self-conscious reflection enters into the mix and we are empowered by both our conceptual as well as our technological capacities to the point of being able to choose our diets. That choice is what renders us moral agents in a way that marks us different from other animals. Humans are in the unique position to have the capacity to choose to cause less suffering in order to stay alive.

If we can thrive off of vegetables, why do we choose to keep inflicting unnecessary suffering on billions of sentient creatures every year? Today, with the advent of factory farming, the suffering caused by eating animals is not just limited to the slaughter itself; that process is rather humane compared to the extended torturous life conditions we subject countless birds and cows to in the lead-up.

The Emergentist worldview, however, allows us to avoid extremes on both sides of these ethical issues.

The materialist/reductionist perspective is one of these extremes, which generally disregards animal consciousness as either nonexistent or negligible. The early reductionist René Descartes famously dissected live dogs because his modern philosophical viewpoint led him to believe that animals do not possess a rational soul and therefore are no more than automatons or machines. Few reductionists today would be so barbaric, of course. (And yet, go to a conventional factory meat farm today and you may not be so convinced of that.)

Traditional Christianity, especially of the fundamentalist flavor, provides another example of this sort of extreme position. It finds justification not in philosophy but in its holy scriptures for total subjugation of Earth and its resources—including all animal life—to the sole benefit of human beings, who alone are made in the image of God. For instance, in the very first chapter of the Bible, we read:

God blessed [Adam and Eve] and said to them, “Be fruitful and increase in number; fill the earth and subdue it. Rule over the fish in the sea and the birds in the sky and over every living creature that moves on the ground.” Then God said, “I give you every seed-bearing plant on the face of the whole earth and every tree that has fruit with seed in it. They will be yours for food. And to all the beasts of the earth and all the birds in the sky and all the creatures that move along the ground—everything that has the breath of life in it—I give every green plant for food.” And it was so. (Genesis 1: 28-30)

Such verses have helped sanction the wholescale domination and exploitation of the vegetal and animal kingdoms in the religious West.

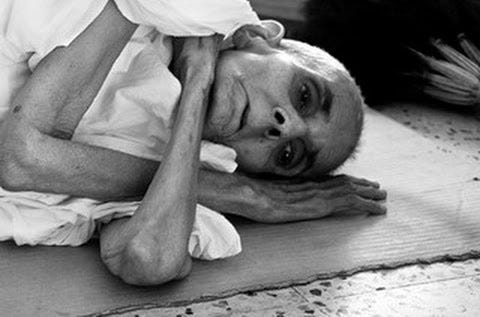

Other religious traditions, however, have gone to the other extreme—with horrific and disastrous results of a different kind. In Jainism, for instance, adherents are so eager not to risk killing any living creature of any kind that they walk with brooms to brush away bugs by their feet and wear masks to avoid killing microorganisms. There is even a sanctioned practice of starving oneself to death out of the conviction not to harm any living being—including plants.

This is misguided religion in the extreme, which, as in most cases, stems from the best of intentions but leaves a stream of guilt, suffering, and death in its wake.

The Emergentist attitude avoids these terrible extremes and forms of absolutist thinking, with a dietary ethic rooted in both complexity science and common sense. The fact is, all complex life lives off of other life. That is the nature of the Universe, built into the process of complexification itself, as organisms become more complex by feeding off increasingly organized free energy in their environments. Indeed, we cannot truly valorize complexification, and thus the realization of God, without admitting and, in some ways, celebrating this fact. But this does not mean we carelessly embrace the infliction of suffering on other beings; nor does it mean we starve ourselves out of existence to leave the world for the bugs.

Here, the Great Spiral of Becoming can be our guide for considering what is more or less justified to be killed for food. In short, reductionists and traditionalists have had far too high a threshold, drawing the line of what could be eaten at the level of Culture (i.e., anything but humans!). Radical ascetics, by contrast, have had far too low a threshold, wary to let even Life into the domain of the edible (i.e., not even plants!). Informed by complexity, Emergentists draw the line at (or low down) the level of Mind (i.e., anything but animals with complex nervous systems!), where the phenomenological experience of pain and suffering actually enter the cosmological mix.

Generally speaking, then, an Emergentist living by their convictions will be inclined to hold to an essentially vegetarian diet in an effort to minimize the suffering experienced by sentient life, while still optimizing for their own health, well-being, and complexity. When asked why he was a vegetarian, the famous spiritual thinker Alan Watts responded: “Because cows scream louder than carrots.” Embedded in this pithy witticism is an important spiritual insight, one supported by our new understanding of hierarchical complexity.

Such an understanding avoids pernicious absolutisms by recognizing the relativity of all entities and organisms within the Wisdom Stack. It sees a spectrum where others see only dogmatic black-and-white. For instance, Emergentism asserts that it is wrong to subject animals to slaughter. However, we are also obliged to note, it is worse to do so to pigs and cattle than to insects and fish, given their relative complexities and place in the phylogenetic chain.

But would it be better to eat a cow than to let a human starve? Indeed, we are inclined to say that it would. For we can affirm the special position occupied by human beings owing to their self-conscious complexity—without adopting the traditional notion of some divinely sanctioned human supremacy over all the animals.

On the other side of the coin, understanding the scale of complexity and consciousness also frees one from the crippling religious angst over, say, ever harming a fly. There is a very real difference between swatting a mosquito and killing a baby. Such common sense isn’t always so common, apparently. But these intuitions are given some theoretical justification through complexity science. It is just as inhumane and repugnant for a human to starve themselves out of piety as it is for one to gorge themselves out of rapacious desire.

Emergentism celebrates Life, but also recognizes that it is always in a state of relativity. Here, complexity is key, not just in considerations of conscious depth (and thus the capacity for suffering) but also in regard to how nuanced we can allow our own thinking to be. Absolutist simplicities are dangerous; when applied to ethics, they can be downright destructive. Emergentists see life in context, and that requires a more subtle and contextual approach to issues of morality.

Such a perspective allows the Emergentist at the level of Culture to both celebrate the wonder of all Life’s forms even as she consumes some in order to maintain her own existence; to appreciate that thriving healthfully requires both wonder and judicious indifference (say, to the eradication of a culture of E. coli, for instance).

The world is complex, and endlessly interwoven. Such complexities require discernment, not moralistic absolutes, and that is another spiritual virtue of Emergentism.

NEXT: Level 3 (Mind) and Level 4 (Culture) Practices

Buy the full book here:

Inspired by what l’ve read ✨