Emergentism | Lineage: 1. Eastern and Western Mysticism

Tying Back

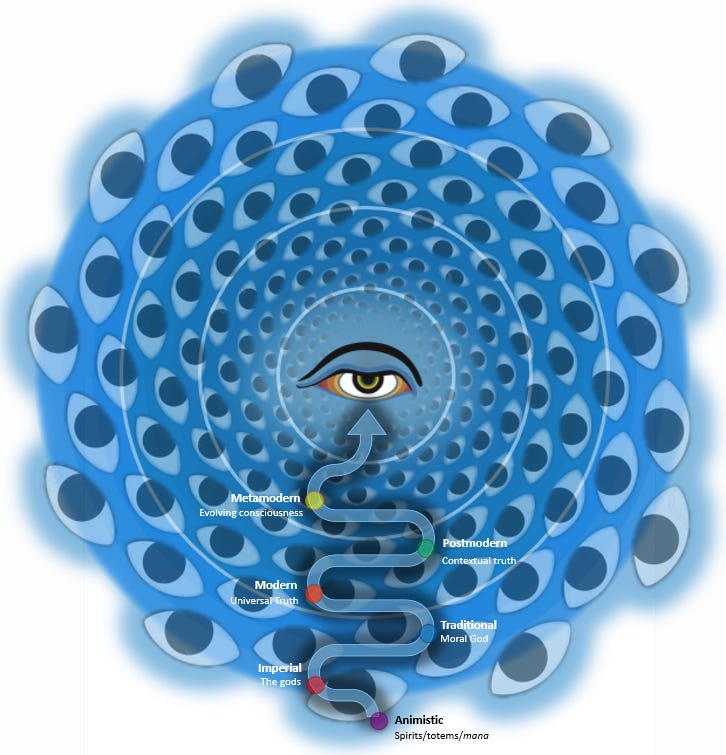

Emergentism is a novel spiritual framework informed by the revelations of complexity science, non-equilibrium thermodynamics, consciousness studies, developmental psychology, and other cutting-edge disciplines. At the same time, the ideas that it speaks to are actually surprisingly ancient.

Perhaps you have gotten the sense while reading these pages that the story it tells rings with a certain unmistakable familiarity? Like a song you’ve heard hummed or hinted at a thousand times but only now listened to in full. It is worth asking, What is the significance of this deep resonance?

The relationship of the Emergentist vision to the rich spiritual heritage of humanity is nuanced, and appreciating both its novelty and its antiquity in their fullness requires holding a few different realities in mind simultaneously. The futurists and civilization designers excited about a genuine upgrade to religion are not at all wrong to see in this religion of complexity something truly innovative. At the same time, those wary of shiny new isms without tradition or pedigree can find assurance in the deep ties that ground this new religion in enduring wisdoms.

Science and religion have been antagonists of one another for so long that finally witnessing their healing and even converging can bring out the partisans in us. Are we moving forward and triumphantly progressing knowledge?, some demand to know—while others ask, Are we deepening our roots and humbly taking up the mantle of timeless truths that the ancients so thoroughly pioneered for us? Well, Yes.

The answer to both question is Yes, we are.

With the maturation of the sciences out of reductionism and into the neo-holistic perspective we have been considering, the split between reason and religion is disappearing. Science has not proved nor disproved religion; nor has religion triumphed over science. Rather, both have been transformed by the other, with religion learning to adopt the methods of empiricism and critical scrutiny and science learning to speak in the language of meaning and purpose. The result is not some strange truce between traditional religion and modern science, then, but more like the formation of a new category altogether, a “religion that is not a religion,” in which a Universe of meaning and sublime significance is simply, well, the best explanatory theory.

In drawing connections with spiritual and philosophical traditions of the past, we are not simply suggesting that the ancients possessed the pure and eternal truth that science is now corroborating. Such a claim flies in the face of the very essence of Emergentism—namely, that knowledge grows, truth evolves, and information increases from past to future. Rather, we are invited to consider the continuity of wisdom’s development, to see the present truth prefigured in the past, to find our story told by the ancestors in their own way. In doing so, our timely truth not only gains a sense of heritage, antiquity, and depth, but we also come to new insights about it when placed in the context of a deeper intellectual tradition.

Such is one meaning of religio: a “tying-back” to older yet enduring truths. So it is that we can be both innovators and students of the past, looking back with an eye to the future. Indeed, we might even be so bold as to suggest that these ancient wisdoms become more fully intelligible precisely in the light of the scientifically informed Emergentist narrative.

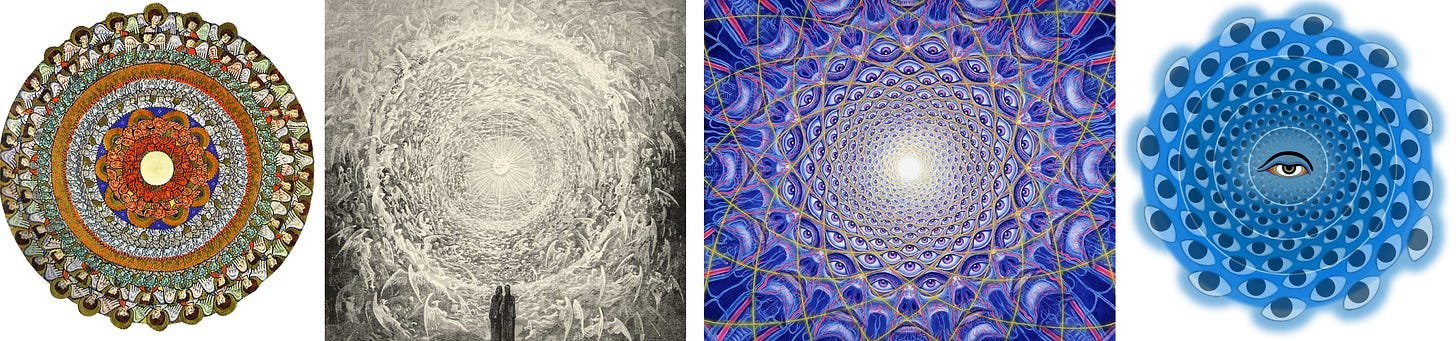

When we allow ourselves to read the great sages of the past through an Emergentist lens, we open up all of human culture as our inheritance. Indeed, the poets, philosophers, and mystics that spoke in their various ways to this great epic of awakening can all be seen as contributing to a diverse theology of Emergentism. In their various systems, schools of thought, angles of approach, or simply evocative images and metaphors, we find the materials of a rich and varied theological landscape. This awakening began in antiquity with the non-dual mystics, but got a huge conceptual upgrade by modern philosophers, before contemporary synthesists and metatheorists helped integrate these insights with complexity science.

Let’s start with the mystics.

Eastern Mysticism

Thousands of years ago, before anyone knew anything about a developing Universe or had anything like the conceptual paradigm of complexity or emergence, mystics were turning inward in the search for ultimate self-knowledge.

In the East, the chief method for such inner reflection was meditation—an intentional training of attention on consciousness itself. By ridding the mind of distractions and all the noisy chatter of the restless internal monologue, yogis gained insight into their deepest essence, just as one is able to see what lies deep down on the floor of the lakebed once the choppiness of the waves on the surface subsides. There, in the depths, they came to a profound and sublime realization: there is no small individual self, but just one Self.

In every “I” there is only the All.

So, for instance, one reads in the Indian Upanishads (c. 600 BCE):

The wise who, by means of meditation on his Self, recognizes the Ancient, who is difficult to be seen, who has entered into the dark, who is hidden in the cave, who dwells in the abyss, as God, he indeed leaves joy and sorrow far behind.

Through disciplined introspection, the mystic came to the transformative insight that, at their core, they were the boundless, limitless cosmos. So another Upanishad reads:

And when, after the cessation of mind, he sees his own Self, smaller than small, and shining, as the highest Self, then having seen his self as the Self, he becomes self-less, and because he is self-less, he is without limit, without cause, absorbed in thought. This is the highest Mystery…

To realize this was to lose one’s small individual form and become united with God (Brahman), the very Personhood of the Universe:

As the flowing rivers disappear in the sea, losing their name and their form, thus a wise man, freed from name and form, goes to the divine Person, who is greater than the great. He who knows that highest Brahman, becomes even Brahman.

So the self unites with the true Self, and all is One. “He who knows this becomes one with the One.”

The same idea can be found in the Bhagavad Gita (c. 200 BCE), the profound scripture so sacred in Hinduism. In this mystical text we learn that, in God consciousness, all differentiations fall away:

When a sensible man ceases to see different identities due to different material bodies and he sees how beings are expanded everywhere, he attains to the Brahman conception.

Such is the condition of absolute Self-knowledge. Or, as it is put elsewhere:

A person is said to be established in Self-realization and is called a yogi when he is fully satisfied by virtue of acquired knowledge and realization. Such a person is situated in transcendence and is self-controlled. He sees everything—whether it be pebbles, stones or gold—as the same.

Such is the nature of God consciousness—attainable in moments of awakening through disciplined praxis. The entire distinction of subject and object disappears, and all is simply One, is Self, is God. As the great Indian mystic and philosopher Shankara (c. 700 CE) put it: “So long as some-thing is still the object of our attention we are not yet with the One. For where there is nothing but the One, nothing is seen.”

Western Mysticism

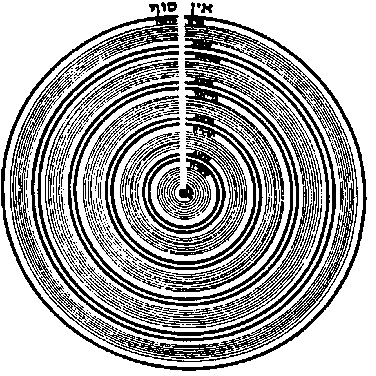

Such is the mystical experience of God consciousness, which has been attested the world over. Indeed, the mystics of the West relate their own experience with this shape of consciousness. The great Neoplatonic sage Plotinus, for instance, was a Roman mystic and philosopher who lived in the third century CE. Having numerous absorptions into God consciousness, he was deeply acquainted with the non-dual unity experience, wherein the subject/object distinction falls away.

“In the assertion ‘I am this particular thing,’” he says,

either the particular thing is distinct from the assertor – and there is a false statement – or it is included within it, and, at once, multiplicity is asserted: Otherwise the assertion is ‘I am what I am,’ or ‘I am I.’

It is compelling to think that this simple insight of God consciousness, “I am what I am,” was the original basis for the name of God in the Abrahamic tradition: Yahweh, which means in Hebrew “I am what I am” or “I am what I shall be.”

Whatever the case, such is the experience of the mind in the state of pure God consciousness. So Plotinus writes:

Knowing God and his power, then, it knows itself, since it comes from him and carries his power on it; if, because here the act of vision is identical with the object, it is unable to see God clearly, then all the more, by the equation of seeing and seen, we are driven back on that self-seeing and self-knowing in which seeing and thing seen are undistinguishably one thing.

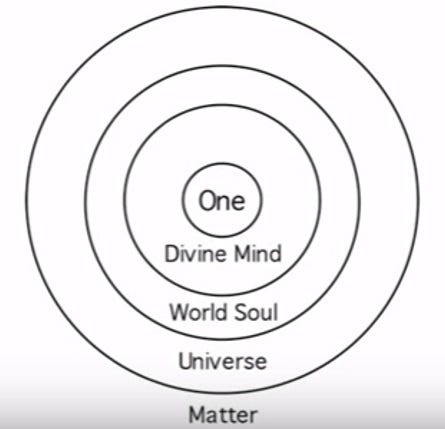

Interestingly, Plotinus was one of the chief architects of what would become formalized as the Great Chain of Being. His philosophy thus speaks not only to the God consciousness at the source of reality (which he called “the One”), but also to the graded levels of reality that lead up to it. And while his thinking about these levels was limited to the metaphysical conceptions of his day, his work still stands as a powerful and evocative source of theological material in a proto-Emergentist vein.

The work of Plotinus and his school of mystical philosophy, Neoplatonism, would have a huge impact on later Christian and Islamic mystics. So, for instance, the incredibly influential Christian Neoplatonist Pseudo-Dionysius (c. 500 CE), who notes that all worldly knowledge, because it is based on a subject-object duality of knower and known, becomes transcended in God consciousness, where seer and seen are one, and so occluded in a “divine darkness.”

To this one can compare the work of an anonymous mystic called The Cloud of Unknowing (c. 14th century CE), where transcendent unifying knowledge is also spoken of as a radical darkness beyond duality.

The works of the German mystic Meister Eckhart are exemplary of these insights. In one text, Eckhart speaks of the attainment of God consciousness in clear and concise terms. “The Knower and Known are one,” he asserts.

“Simple people imagine that they should see God, as if He stood there and they here. That is not so. God and I, we are one in knowledge.”

Elsewhere he writes:

It must be understood that this is all the same thing: knowing God and being known by God, and seeing God and being seen by God. We know God and see him because he makes us know and see. Even as the luminous air is not distinguishable from its luminant, for it is luminous with what illumes it, so do we know by being known, by his making us conscious.

The realization of such God consciousness led Eckhart to make a distinction between the “God” often spoken of in religious contexts, who is said to do this or that in generally anthropomorphic terms, and the “Godhead,” which is the true God consciousness transcendent to all such expressions: “God and Godhead are as distinct as heaven and earth. Heaven stands a thousand miles above the earth, and so the Godhead is above God. God becomes and disbecomes.—Whoso understandeth this preaching him I wish well.”

“God,” then, is transient, changing, even mortal, whereas the Godhead stands above all this flux in truly transcendent fashion—the God, we might say, to the lesser shapes of God endlessly approximating It.

We find, then, in mysticisms both East and West, a shared experience, a shape of consciousness in which the subject/object distinction falls away and one is left with only a pure state of (Self-)awareness, where knower and known are one, and to even call something God would be to imply there is an “other” to be so called, which there is not. This non-dual state is thus akin to the attainment of ultimate knowledge, because the thing known is known as intimately as one’s own self. In this sense, ultimate knowledge is the same as ultimate Self-knowledge.

At the same time, to even use the word “knowledge” becomes too limited, since knowledge usually means knowledge of something, and this presumes a duality of knower and known. Non-dual knowledge therefore represents a categorically different sort that transcends all other knowledge precisely where it ceases to be “knowledge.” This transcendental knowledge is thus perceived as a kind of “non-knowledge,” the negation of knowledge through the transcendence of knowledge. Absolute knowledge culminates in the apophatic silence, the cloud of unknowing, the dark light of God.

NEXT: Lineage 2: German Idealism

Buy the full book here: